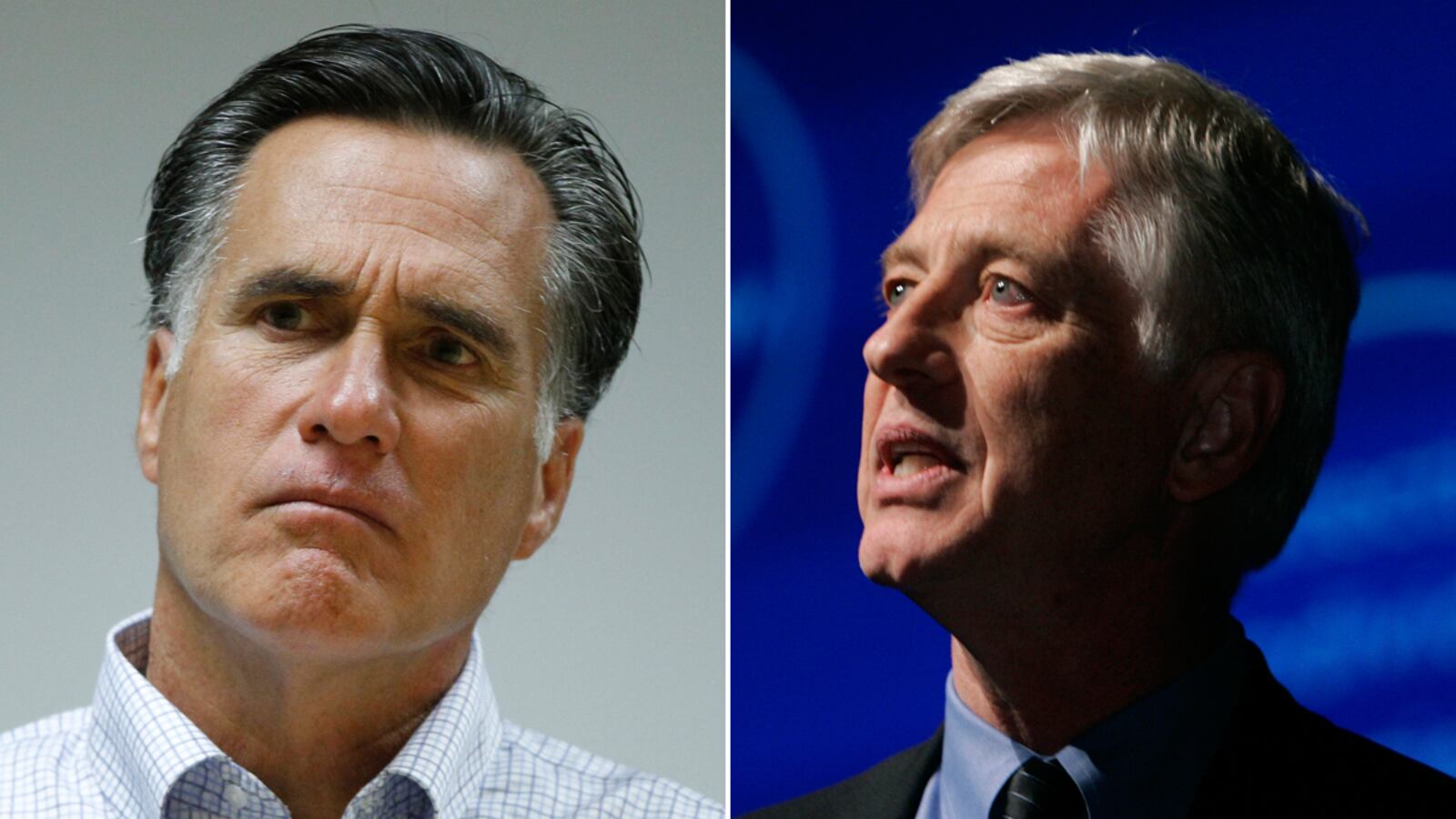

One evening, years before Rocky Anderson was elected mayor of Salt Lake City—where he would eventually make a name for himself as Utah’s liberal lion—he was invited to a dinner party where he was told Mitt Romney would be attending.

“I had no idea who he was,” Anderson recalls. “I had to Google him.” The search results revealed an impressive resume, but little hope for sparkling dinner conversation: a mega-rich private-equity wizard who had tried (and failed) to run Ted Kennedy out of the Senate? Anderson expected a Republican stiff.

“So, I get up there and I’m greeted by this young, vivacious, friendly guy,” Anderson says. “I’m looking around to find the stodgy person I thought I would meet, but no, that was Mitt. That’s the kind of person he is...” he pauses briefly, and then adds, “Or at least was. Who knows now?”

If Anderson’s compliment sounds strained, it’s only because the man he met at that dinner party years ago bears little resemblance to the candidate currently running for president. Romney has often been accused by political foes of opportunistic flip-flopping, but Anderson’s critique is sharper—and more personal. After all, Romney’s perceived campaign transformation didn’t just cost him Anderson’s endorsement; it cost him their friendship.

According to Anderson, the two men got to know each other when Romney was hired to rescue the 2002 Winter Olympics from financial ruin. The mayor admired Romney’s inclusive, hands-on approach to problem-solving, specifically citing an incident with animal-rights activists who were upset that the Winter Games was associating itself with a rodeo. “Mitt didn’t send the second, or third, or fourth-chair person to meet with them,” says Anderson. “He came over to my office, I invited them over, and by the end of the meeting everyone was on the same page. He had a way of making people feel like they’d been heard. I’ve never seen Mitt Romney exude any sort of arrogance.”

As they worked together, they grew to be close friends. “I felt like I had a much better personal relationship than he had with any other elected official here,” says Anderson. “There are some very mean-spirited right-wing whackos in our legislature, and Mitt tried to get along with them… but he was really gritting his teeth a lot of the time.”

He fondly remembers enjoying the “wonderful senses of humor” possessed by both Romney and his better half, Ann. “I love his wife,” says Anderson. “She would be a good, mainline Democrat if she weren’t married to Mitt.”

Romney made no secret about his gubernatorial ambitions, and the two would occasionally talk politics. It was during these conversations that Romney revealed himself to Anderson as the socially moderate Republican who would go on to win the governorship in deep-blue Massachusetts. In fact, Anderson recalls one conversation during which Romney explicitly told him he was pro-choice, that Roe v. Wade was “settled law,” and that as far as he was concerned, the legal debate over abortion was over. (Romney now says states should determine their own abortion laws, and not be ruled by “judicial mandate.”)

By the time the Olympics ended in 2002, Anderson had become such a fan of Romney’s that he crossed party lines to endorse his friend in the Massachusetts gubernatorial race. Speaking directly to the camera in a campaign commercial that was aired repeatedly throughout the state, he put up a bat signal for Bay State progressives by saying, “Take it from this liberal Democrat, if you want an amazing leader, vote for Mitt Romney.” A year later, Romney returned the favor and endorsed Anderson in his mayoral re-election bid.

“I really had tremendous respect for the man,” Anderson says, summing up his feeling for Romney at the time. But all that changed in 2007, when Romney decided to run for president.

Facing a GOP primary in which culture-war issues ruled the day, Romney positioned himself as a family values crusader, tacking sharply to the right on issues like stem-cell research and abortion. Anderson, meanwhile, had become a fierce and vocal critic of the Bush administration, earning national attention as he called on Congress to impeach the president.

When Romney’s primary opponents began alerting the press of the candidate’s friendship with the liberal mayor, the campaign immediately began inserting some rhetorical distance between the men.

“He was a mayor that worked well with me during the Olympics, and I supported his work as a mayor,” Romney said in an interview. “I do not endorse or support his views on President Bush or almost any other issue particularly that’s unrelated to being a mayor.”

For Anderson, who had found many areas of agreement during their time together in Salt Lake, Romney’s comments represented a betrayal of his “firmly held views”—and reason enough to lose respect for his friend. Anderson fired back, accusing his friend of giving up his own personal integrity and “caving to his handlers.”

Today, Anderson’s criticism of Romney is even harsher. “He seems to be among a whole group of political prostitutes who are willing to back off of positions that matter a lot… in order to win elections,” says Anderson, who recently left the Democratic Party, citing its ineptness at pursuing meaningful energy policy, financial reform, and prosecution of human rights violations.

The ex-mayor insists his lost faith in Romney is due entirely to questions of policy, not personal offense. He even says he feels sorry for the candidate: “I think Mitt would privately say he wishes there weren’t so many nuts in the Republican Party that had gained so much clout." But he admits that the fallout in 2007 may have damaged their relationship.

“When he comes to Utah, he doesn’t call me anymore,” says Anderson. “I used to get invited to things, receptions and things, when he came to town, but he just doesn’t want to be seen with me.”