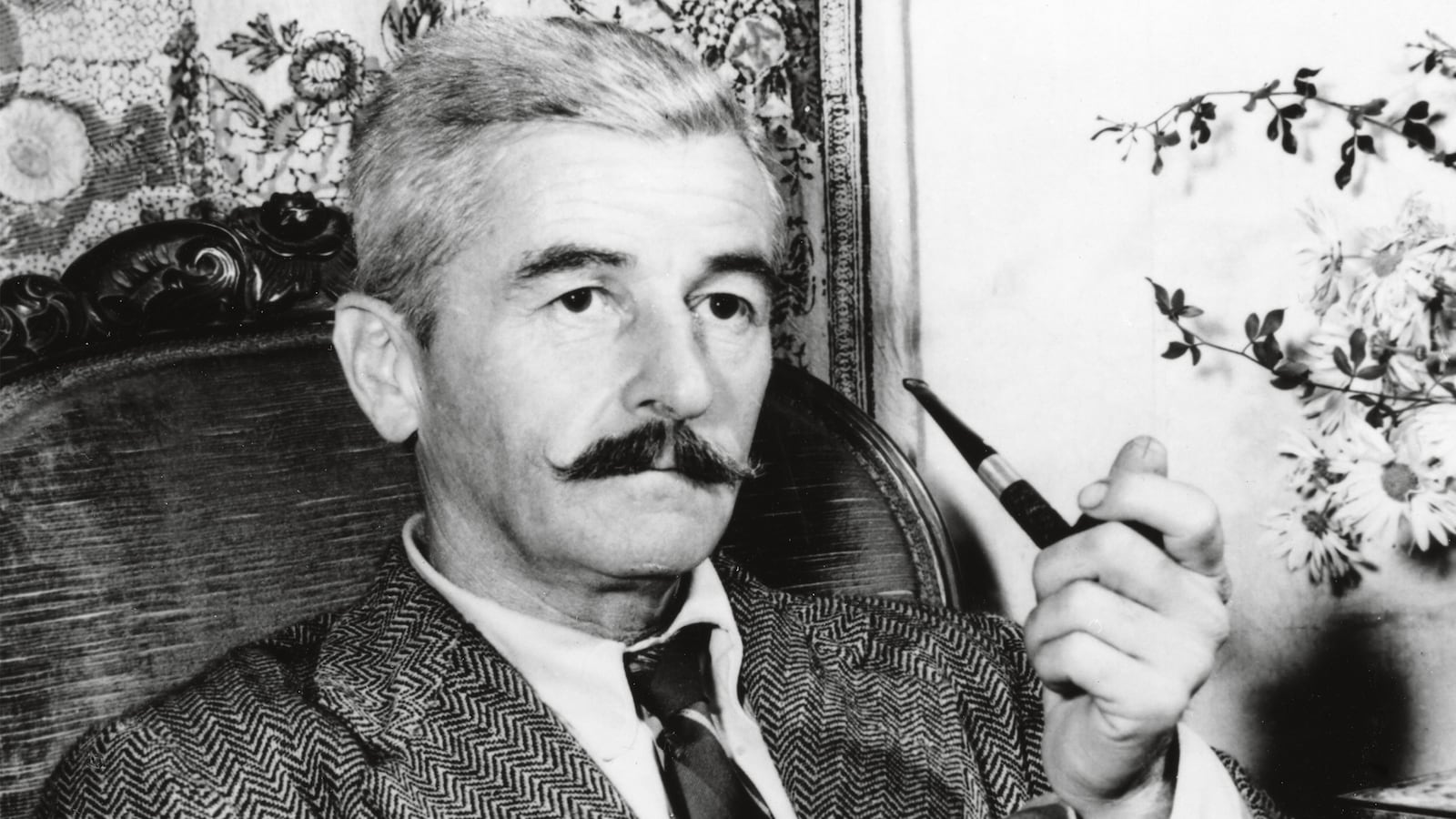

William Faulkner had recently begun a draft of “Dark House,” the novel that would ultimately become Absalom, Absalom!, when he arrived in New Orleans on February 15, 1934. He came to attend an air circus that was being thrown to celebrate the opening of Shushan Airport, which is now New Orleans Lakefront Airport. He flew there himself from Batesville, Mississippi, having earned his pilot’s license two months earlier. But he arrived a day late. Everybody was talking about what had happened the previous evening, on opening night. A pilot named Merle Nelson had crashed his “comet plane”—its wings were equipped with a device that shot flames—into the ground, where it exploded.

Faulkner was at Shushan a few days later when a parachute jumper, who had nearly died when he was late to open his parachute on a previous run, opened his parachute too soon. The lines wrapped around the tail of the airplane and the jumper dangled in the air. The pilot, a free-agent barnstormer who had brought his plane to New Orleans without invitation in the hope of getting on the bill, appeared to try to rescue the jumper, but that might have made matters worse, for the plane dove toward Lake Pontchartrain. The crowds watched in terror from the grandstands. Among the witnesses was the pilot’s wife, cradling their infant child. The jumper’s demolished body was later found in the lake. The pilot was not.

These events became the basis for a short story that Faulkner wrote in the next two months, “This Kind of Courage,” about barnstorming pilots, which he failed to publish. Later in the year, while working in Hollywood on a western named Sutter’s Gold with Howard Hawks, he bellyached about his struggles with Absalom! Absalom! “I got mad at him,” Hawks later said, and told him I got so sick and tired of the goddam inbred people he was writing about. I said, “Why don’t you write about some decent people, for goodness’ sake?” “Like who?” I said, “Well, you fly around, don’t you know some pilots or something that you can write about?” And he thought a while, and he said, “Oh, I know a good story. Three people—a girl and a man were wingwalkers, and the other man was a pilot. The girl was gonna have a baby, and she didn’t know which one was the father.” I said, “That sounds good,” and he wrote Pylon from it.

That ménage à trois, taken with the events at the air show, form the plot of the novel, which is told from the perspective of a lonely drunk newspaper reporter who becomes obsessed with the lives of a band of flying gypsies. Faulkner himself was boiled during his time in New Orleans—it was Mardi Gras week, after all—and the novel is drenched in an alcoholic haze that extends beyond the story to the characterization and the long, murky descriptive passages. Adding to the disorientation is Faulkner’s decision to set the novel not in New Orleans, Louisiana, but in the fantastical New Valois, Franciana. Apart from the proper names the city resembles its model almost exactly, from its “heavy damp bayou-and-swamp-suspired air” and “palmbordered bearded liveoak groves” to the Mardi Gras “curbmass of heads and shoulders in moiling silhouette against the lightglare, the serpentine and confettidrift, the antic passing floats.” As is often the case with Faulkner, it’s not always exactly clear what is going on. But we can be sure it’s depraved, gloomy, and at least moderately deranged. Pylon is a nightmare, and like all nightmares it has its own inscrutable logic and self-indulgent pathos. Proximity to the amoral barnstormers drives the reporter to the brink of insanity, and Faulkner’s prose, crowded with the kind of portmanteau words popularized a decade earlier by John Dos Passos (“gasolinespanned,” “bottomhope,” “coffincubicles”), has a similar effect on the reader.

“They aint human,” is the reporter’s constant refrain. “It aint adultery; you cant anymore imagine two of them making love than you can two of them aeroplanes back in the corner of the hangar, coupled … cut him and it’s cylinder oil; dissect him and it aint bones: it’s little rockerarms and connecting rods.” The reporter turns his home into a caravansary for the three lovers, their mechanic, and their young child during the week of the air carnival. He brings home a jug of absinthe for entertainment. The gypsies’ arrangement, and their strange abandon, excite and terrify him equally. They are not after money, it would seem, but glory. Even so they risk their lives in air races for meager cash prizes. The reporter does not know whether to be repulsed or to join them. To the pilot he says:

Sometimes I think about how it’s you and him and how maybe sometimes she dont even know the difference, one from another, and I would think how maybe if it was me too she wouldn’t even know I was there at all.

But the female jumper is not interested in the reporter, and he finally realizes that he isn’t cut out for the barnstormers’ life. He can only watch them in wonder, taking a perverse thrill in their misfortunes, with the same predatory fascination of the crowds at Shushan gazing up at the daredevil aviators in the air circus.

Americans all over the nation were finding themselves in the same sort of grim delirium in 1935. The Great Depression was in its sixth year, and Franklin D. Roosevelt was entering the third year of his administration. The confidence that had bloomed since his election was swiftly deflating. The economic recovery had stalled. The New Deal had begun to come under criticism from both the right, which opposed its “dictatorial” assault on free enterprise, and the left, which accused Roosevelt of engendering harmful class conflict. Father Charles Coughlin attracted an enormous following on his radio show by blaming FDR for failing to punish sufficiently the “money powers,” and Louisiana’s Gov. Huey Long, then a senator, attacked FDR for failing to raise taxes sufficiently, and began plotting a presidential campaign. In the spring of 1935 the Supreme Court unanimously invalidated the National Industrial Recovery Act, the centerpiece of the New Deal. When asked what could be done in light of the court’s decision, Roosevelt responded that the answer might take “five years or ten years” to figure out. But to many that seemed optimistic.

For relief the nation turned to distraction and brainless amusement—to epic historical novels and films, self-help books, and public pageants like air circuses. In Pylon Faulkner writes about the grotesque fruits of industrial mechanization, which not only put men out of work but subjugated them to the will of powerful machines that ghoulishly mocked nature (a crashed airplane is described as “lying on its back, the undercarriage projecting into the air rigid and delicate and motionless as the legs of a dead bird.”). He writes about mob mentality and about the tragedy of a society that sentences so many of its members to “irrevocable homelessness.” But his main subject is loneliness. It is the kind of loneliness brought on by long desperation, a loneliness that becomes so acute that it makes one impatient for something drastic to happen—anything, even something as horrible as an airplane exploding mid-flight and crashing into a deep lake, leaving no survivors.

Other notable novels published in 1935:

Tortilla Flat by John SteinbeckIt Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair LewisOf Time and the River by Thomas WolfeLittle House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls WilderA House Divided by Pearl Buck

Pulitzer Prize:

—Now in November by Josephine Johnson

Bestselling novel of the year:

Green Light by Lloyd C. Douglas

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2014. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.—Nathaniel Rich

Previous Selections

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson 1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin 1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux 1992—Clockers by Richard Price 2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain 1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London 1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather 1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton 1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West 1943—Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles 1953—Junky by William S. Burroughs 1963—The Group by Mary McCarthy 1973—The Princess Bride by William Goldman 1983—Meditations in Green by Stephen Wright 1993—The Road to Wellville by T.C. Boyle 2003—The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2013—Equilateral by Ken Kalfus 1904—The Golden Bowl by Henry James 1914—Penrod by Booth Tarkington 1924—So Big by Edna Ferber 1934—Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara 1944—Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith 1954—The Bad Seed by William March 1964—Herzog by Saul Bellow1974—Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig1984—Neuromancer by William Gibson1994—The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields2004—The Plot Against America by Philip Roth2014—The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henríquez1905—The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton1915—Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman1925—Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos