In The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, the title character endures an extraordinarily wild ride. From his balcony in what looks like the French Quarter in New Orleans, he is swept away by a Katrina-like storm so powerful that it can blow the words right off the pages of a book. Dumped into a black-and-white landscape littered with wreckage, especially ruined books, Morris encounters a savior of sorts, a young woman held aloft by a bouquet of balloons. The woman and her balloons, in contrast to all around her, are in full color. Smiling down at Morris, she tosses him a book—a flying book—that leads him to a library set out in the countryside. Here he takes up residence, learns to care for the thousands of books he lives with (books on the verge of dying are resuscitated by reading them) and begins to write down his own story, an effort that takes him all his life. When he is done, he leaves and becomes young again. The book that he left behind, his contribution to the library that nurtured him, flies into the hand of a young girl who appears on the doorstep of the library. Life is restored. Life goes on.

The ride that Morris takes in the story, however, is nothing compared to the journey the story itself has taken so far—a journey that began as a few sketches on a legal pad and then wound its way through the worlds of children’s lit, animated film and on to the uncharted world of book apps for the iPad, where a little story about the love of books has actually outsold “Angry Birds,” at least for a few days.

Initially conceived several years ago as a children’s book by its creator, William Joyce, the astonishingly prolific filmmaker (Robots), children’s television show creator (Rolie Polie Olie), and children’s book author (Dinosaur Bob, Santa Calls), the story instead first became an award-winning animated short film, produced at his Moonbot Studios in Shreveport, Louisiana, his hometown. “I thought, we’ll do the short film,” says Joyce, “and it’ll be a nice promotion piece for the book that will then come out.” But while the film was still in production, Apple introduced the iPad, and Joyce and his crew suddenly found themselves making other plans. Morris Lessmore would still be a book—some day. But before that, it would become a book app.

“Apple had the first demonstrations for what they wanted the iPad to be and do, and we were like, this is what we’ve been waiting for,” says Joyce, sitting in Moonbot’s conference room, where the walls are covered with almost a dozen different storyboards of planned books and films—stories for toddlers, for young readers, and for adults. “It was like, we’ve got the assets to do an iPad version, so let’s have fun with what this iPad can do and still stay true to the story’s origins as a book. “

The film had a musical soundtrack but no narration and no dialogue. More than anything, it evokes the “show, don’t tell” ethos of silent movies (Morris bears a more than passing resemblance to Buster Keaton). But, as Joyce points out, “the story’s about the love of books and the importance of books and the power of books and the power of story.” So when it came to designing a book app, “we have turning pages, we have a narrator, and we have a text. If we had done an app about bouncing balls, we wouldn’t have had any of those things. It would seem silly to have turning pages for something like that. But this is about books. So we used all that to—I hope—our narrative advantage.”

He promises that come the fall of 2012, there will be a book version, “and it will have things that we can’t have done in the short film or the app. It will be the actual tactile thing. It’s totally backwards, but why the hell not?”

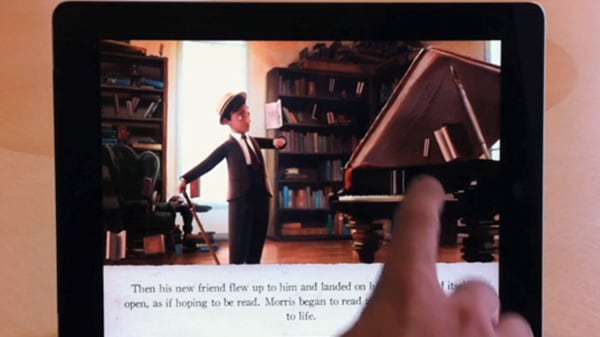

Released in late May, the app has received glowing reviews and sold briskly, at one point selling more than more than 25,000 copies in one week. No surprise there, at least not to anyone who spends more than a few minutes playing with the story. And play you will. In every scene, the viewer has to help move the action along—speeding up the wind that carries Morris away, spinning the house on which he flies through the storm, spelling out words in the cereal bowl with which Morris feeds the books (cereal like Alphabits, of course). But the interaction is not merely some computer form of a pop-up book. Besides spelling words, you can play a piano keyboard and make the books dance, and if you don’t want narration, you can mute it, and if you don’t want text, you can remove that, too. You can’t change the story, but the app designers have nevertheless found ways to make you feel very much a part of the story. Only the most hardcore print junkie would turn up his nose at this new reading experience.

Morris Lessmore is only the latest—but one of the best—of several examples of book apps that put ordinary e-books to shame. Check out the recently released apps for The Waste Land or On the Road, and you will quickly see the possibilities for amplifying and enriching the reading experience—possibilities so far not found on mere e-books, where the whole idea (out of guilt perhaps) seems to be to recreate the ordinary experience of reading a book, just without the book.

Joyce has no intention of walking away from books. This fall, he will publish The Man in the Moon, the first of a multi-book series, The Guardians of Childhood, a sort of superhero mythology explaining the origins of Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy, and the Sandman. The series will feature both short novels and picture books and will be followed by a film from Dreamworks.

Still, he admits to a pang or two of anxiety while working on the app for Morris Lessmore, worrying, “I’m going to do this thing and it’s going to doom the things I love. I thought librarians would be afraid of it, like I’d brought in a jar of anthrax spores. But what I saw was people embracing and loving the bookishness of it. It made them want to have the book. Whatever the future’s going to be, part of it is going to be working this way. People aren’t going to quit buying books, they’re still going to want to own the books they love.

“Everything in this room,” he says, gesturing at the storyboards lining the walls, “is a book first and then we’re thinking of other ways it can be interesting. And that’s not murdering the thing we love. It’s expanding the thing we love and embracing the world it’s going to inhabit.

“There are people who are just going to want to do books, and that’s great. But I have always been dissatisfied with the boundaries of every single thing I’ve ever worked in—movies, television shows, books, everything. I always want to put in more. Maybe it’s self-indulgent, but there’s always more in my head than I have room for. So this gives me more room. For certain people this is going to be an interesting time."

As for his own opinion of what he and the Moonbot crew have wrought with the app for Morris Lessmore: "I think it’s a nice beginning. But I think we’re still in Tinkertoy land.”