When forced to comment on an especially touchy issue—NSA surveillance, say—President Obama’s go-to rhetorical gambit has been to call for a “debate,” sometimes a “conversation,” often in service of “striking a balance” between two obviously important things. It’s good tack, particularly when Obama is playing defense. He’s actually found a way to deliver the no-content statements of a politician while portraying himself as a contemplative law professor.

But what makes it such an effective dodge is that the deep ethical dialogues he is pretending to kick-start rarely ever happen, at least not in the federal office buildings of Washington, D.C. To the extent that elected officials indulge in normative language—moral “shoulds” and talk of “values”—it’s either to assert something painfully banal or, more often, to dress up some compromised piece of public policy.

If you’re inclined to lament this fact, don’t. Anyone who expects political tacticians to get into the nitty-gritty of what our values and our rights and our moral beliefs demand has made a serious error. It’s not that such discussions aren’t deeply needed; it’s just that American politics isn’t set up for that kind of thing. What is worth fretting about, however, is that, if we’re honest, most of us don’t even know what such a discussion would look like. This is, of course, understandable; intellectually honest moral arguments rarely make for good copy.

It’s impressive, therefore, that with his new book Would You Kill the Fat Man? The Trolley Problem and What Your Answer Tells Us About Right and Wrong, journalist and philosopher David Edmonds not only takes us into the weeds of ethical deliberation, but does so in a way that is actually readable—at times compulsively so. The book is a walking tour of moral philosophy organized around one of the most well-known thought experiments of the last half century: the trolley problem.

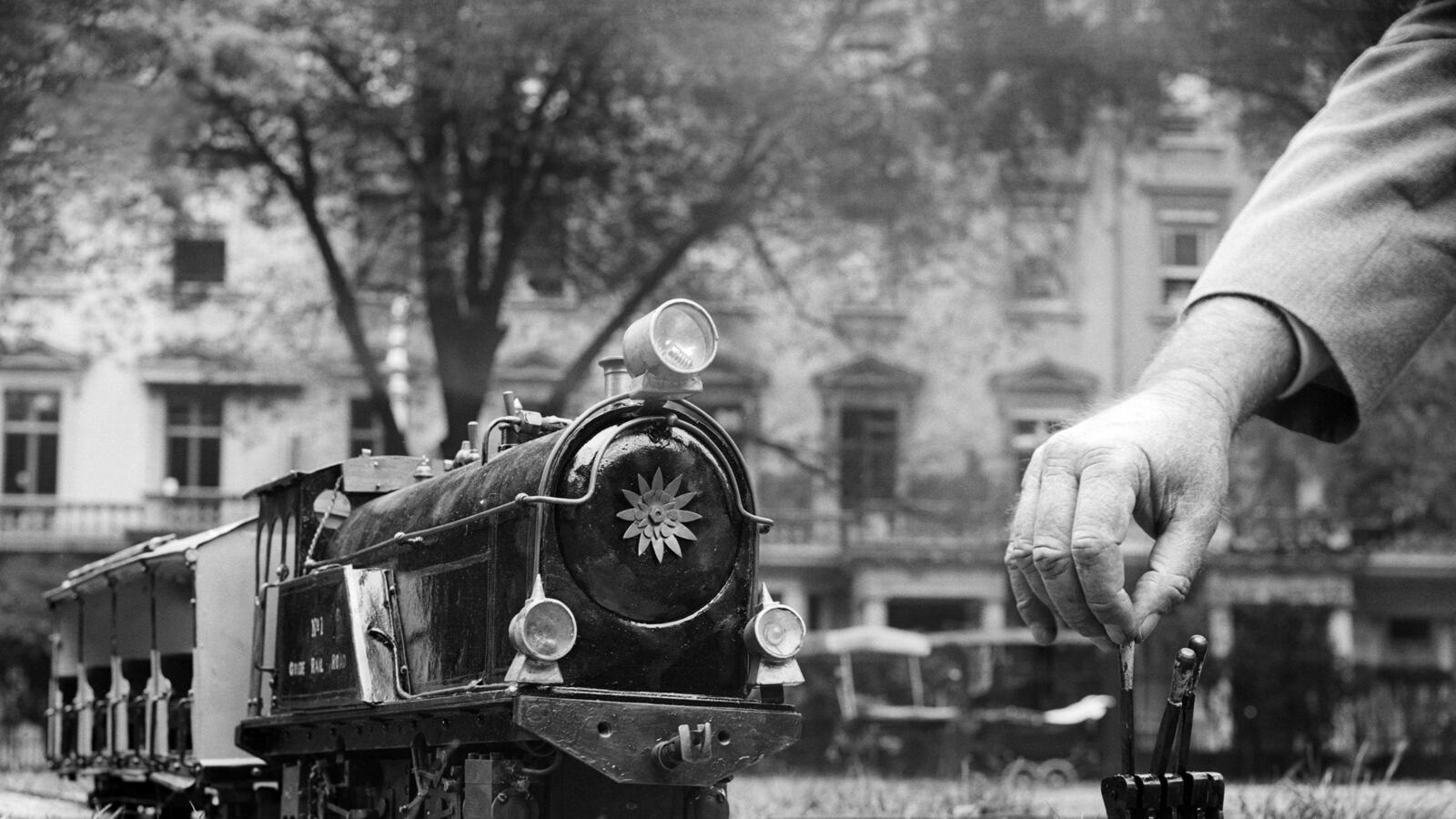

In it’s simplest form, the trolley problem goes something like this: You find yourself standing beside a train track one afternoon, when you notice a runaway locomotive—sometimes a trolley—barreling your way. Up ahead you see five innocent people tied to the track about to meet certain death. Next to you is a signal switch that will divert the train down a sidetrack or “spur.” Problem is, tied to the spur is yet another individual. If you do nothing, five people will die. On the other hand, throwing the switch will prevent the death of the five up ahead, while causing the death of the man on the alternate track. What should you do?

The example is clearly ridiculous, but that’s the point. Thought experiments are intended to isolate our intuitions by filtering out much of the circumstantial noise that can distort our judgment.

As Edmonds tells us, “[m]ost people seem to believe that not only is it permissible to turn the train down the spur, it is actually required—morally obligatory.” At the very least, it seems acceptable to reroute the trolley. The question is: What’s so special about this situation that makes it all right to cause the death of a person who would have otherwise lived?

Things get even hairier when you consider the different versions of the thought experiment that have made the rounds over the years. As Edmonds tells us, “philosophers have come up with ever more examples, involving runaway trains and bizarre props: trap doors, giant revolving plates, tractors and drawbridges.” The most famous spin-off might be Judith Jarvis Thomson’s “Fat Man” example from which the book takes its title. This time you’re standing on a footbridge above the track instead of next to a switch. The train is once again on a collision course with five innocent people. Next to you on the bridge stands an obese gentlemen. Again, if you do nothing, five will die. If you push the fat man onto the tracks, however, he will stop the train, saving the five, but dying as a result. Would you kill the fat man?

The obvious response for many, including myself, is “no.” But why the change of heart? You’re still faced with the choice of sacrificing one life for the sake of five? Something here needs explaining. And in his attempts to decipher the conflicting intuitions that trolley cases evoke, Edmonds provides a survey of some of the ways philosophers have judged the morality of various actions through the ages.

This includes the virtue ethics of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, who believed, Edmonds explains, that an action was good “insofar as it exhibited the behavior of a virtuous person,” as well as Jeremy Bentham’s stone-cold utilitarianism, which judged an action by “how much pleasure it produced and how much pain was avoided.” Edmonds also considers what recent academic trends like behavioural economics and experimental philosophy—an approach that uses the tools of cognitive science to explore philosophical questions—have to say about trolley examples. Along the way, you get a sense of what an Obama-style “conversation” might actually entail.

Thankfully, Would you Kill the Fat Man? isn’t solely concerned with imaginary tales of streetcar disfigurement. In fact, the book succeeds in large part because Edmonds takes every opportunity to relate the enterprise of “trolleyology’—yes, it’s a word—back to some skillfully chosen events, including an ivory-tower soap opera involving one Oxford philosopher with a name out of a Thomas Pynchon novel: Philippa Foot.

Foot (née Bosanquet) created the original trolley problem in a 1967 article in the Oxford Review. She also happened to be the granddaughter of President Grover Cleveland, a founder of the famine-relief charity Oxfam, and part of a complicated friendship with two other influential female philosophers of her era, Elizabeth Anscombe and the novelist Iris Murdoch. It was an incestuous little circle, characterized by “falling-outs and falling-ins, demonstrations of loyalty and acts of betrayal.” Foot eventually married Murdoch’s ex-lover M.R.D. Foot, among other things, a clandestine agent for England during World War II. After their marriage ended, Edmonds informs us, Murdoch and Philippa Foot “connected almost every corner of the love quadrangle and had a brief affair themselves.”

Aside from being juicy bits of faculty-lounge gossip, these narrative detours serve as nifty little vehicles for real-world examples that could benefit from trolley wisdom. For instance, Edmonds considers the moral implications of the 1894 Pullman railway strikes, during which several workers died at the hands of federal troops – an episode he wryly refers to as a “very public trolley problem” for Foot’s grandfather, then President Grover Cleveland. We’re also invited to evaluate Harry Truman’s use of atomic weapons during World War II, an act that appalled Elizabeth Anscombe so intensely, Edmonds recounts, that she staged a fierce and ultimately unsuccessful effort to deny Truman an honorary Oxford degree in 1956. By weaving together abstract principles, biographical sketches, historical examples, and trendy research in this just-so way, Edmonds has figured out how to illustrate the dimensions and consequences of moral decision-making without sacrificing entertainment value.

The fact that it takes such a carefully executed book to bring these debates to life, however, only underscores how slippery the issues really are. Consider Jarvis Thomson’s explanation of what is special about Fat Man. For her, it’s that we’re violating the rights of the corpulent bridge pedestrian, whereas in the original version of the story, no rights are infringed upon—we’re merely reducing “the number of deaths that get caused by something that already threatens people.”

Edmonds himself, meanwhile, points to Thomas Aquinas’ Doctrine of Double Effect, which draws a distinction between foreseeing a consequence of your action and intending that consequence. In the first example, “we foresee, but do not intend a death . . .” In Fat Man, we’re intending to harm someone, plain and simple.

There’s a healthy tendency to dismiss these kinds of line-drawing disputes as frivolous or, even worse, lawyerly. Trolley examples in particular, as Edmonds admits, have grown so complex as to “stretch the limits of our credulity and imagination—the limits beyond which intuitions become fuzzy and faint.”

And yet, we confront fine-grained moral distinctions all the time, like when the NSA tells us there’s an important difference between monitoring the metadata of our phone calls and monitoring their actual content; or when lawmakers seek to ban some mind-altering substances but not others. How are we to make sense of the judgment that, if you’re a Syrian dictator, killing your own people with conventional weapons is one thing, but using sarin gas is quite another? And then there’s the issue that Philippa Foot was trying to clarify when she created the trolley problem all those years ago: abortion.

Many of us have strong beliefs about these matters and, one would hope, reasons for those beliefs. Even if you see trolleyology as a waste of time, it at least lays bare how truly difficult it is to figure out what those reasons are, much less to determine whether they are any good. It demands a kind of “conversation” that doesn’t lend itself to an 800-word op-ed—and it’s certainly not something we should outsource to the political class, so let’s relieve ourselves of that fantasy right now. Indeed, it might be worth taking to heart a different rhetorical dodge of President Obama’s, one that he used in the wake of the George Zimmerman verdict: “There has been talk about should we convene a conversation on race,” he said. “I haven't seen that be particularly productive when politicians try to organize conversations.”