Last January, the New Zealand police, heavily armed and acting in cooperation with the FBI, raided the sprawling mansion of German-born Internet entrepreneur Kim Dotcom. The founder of the now-shuttered file-sharing website Megaupload.com, Dotcom was charged with racketeering, money laundering, and copyright infringement, which an American indictment estimated had cost the film industry $500 million in lost revenue.

The 300-plus pound Dotcom is the perfect villain, the very picture of mindless excess, an “Internet Dr. Evil” who was snatched from his “Bond villain lair” (according to the always-subtle Daily Mail). Every Dotcom-related news story is illustrated with photos of the overstuffed millionaire acting out his hip-hop music-video fantasy—the bikini-clad women, yachts, helicopters, cigars, and expensive cars (with vanity license plates one would expect from a teenager who just won the lottery: GUILTY, STONED, GOD, HACKER, EVIL, MAFIA).

Since his arrest, the case against Megaupload has partially unravelled, allowing Dotcom to focus on his transformation from greedy hacker to, in the judgment of The New York Times, “something of a cult hero.” Exactly one year since his arrest, Dotcom relaunched Megaupload as Mega.com, a file-trading service featuring sophisticated encryption that, he claims, will immunize him against future legal challenges.

For all of its breathless references to a “Mega conspiracy,” the 72-page indictment against Megaupload upends Dotcom’s argument that the site was “never set up with the intent to be some kind of piracy”; emails between company executives rather baldly demonstrate that this was precisely the purpose of the service. And even without the electronic paper trail, it would require an exceptional degree of credulity to believe that the company was merely providing a convenient repository for cat videos and legally obtained music files.

In a new interview with The Guardian, Dotcom drew parallels between himself and Aaron Swartz, the open Internet activist who committed suicide earlier this month, galvanizing his legion of online supporters. “All I can say,” Dotcom said, “is that I see similarities in the way we have been prosecuted.” It’s an odd comparison. The ascetic Swartz, who never attempted to cash in on the information he “liberated,” was motivated by ideology, not the accumulation of wealth.

But Dotcom is courting Swartz’s supporters, recasting his legal troubles as a battle between an overweening American government and a radical defender of free speech. “I see also similarities and abuses that are happening in the case against WikiLeaks that were happening to us,” Dotcom told The Guardian. Indeed, he recently retained noted human-rights lawyer Robert Amsterdam, who is best known for his work defending opposition activists against authoritarian governments.

The case against Megaupload might not be proportionate, wise, or able to withstand legal scrutiny. So far, it hasn’t. But the outpouring of support for WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and, posthumously, Swartz seems to have pushed Dotcom toward a new line of defense, in which he argues that when Megaupload was shut down “free speech was attacked,” just another example of powerful governments—i.e., the Obama administration—attempting “to take control of the Internet and chill free speech.” Shifting the narrative toward the United States government, which, he says, has become “an aggressive state,” is a simple but effective way of gaining adherents.

Like Assange, Dotcom is now suggesting that he’s the victim of a political conspiracy, in which former Democratic senator Chris Dodd, who now presides over the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), used his influence with Vice President Joe Biden to persecute Megaupload and influence “an upcoming election.” “It would probably have looked very bleak for [Obama] to go to Hollywood and ask them to help him get reelected,” he told The Guardian, “when he couldn't make [the Stop Online Piracy Act] happen for them. So Megaupload became a plan B.”

All of Dotcom’s pronouncements nibble around the edges of truth. He is quite right to warn that governments too often use vague and outdated statutes to expand power; this isn't an elaborate conspiracy but a quotidian fact. And it would hardly be surprising if Dodd leaned on government officials to be tougher on copyright violators—that is, after all, why the MPAA hired a former senator—but to suggest that Hollywood campaign contributions were contingent upon the arrest of Kim Dotcom is foolish.

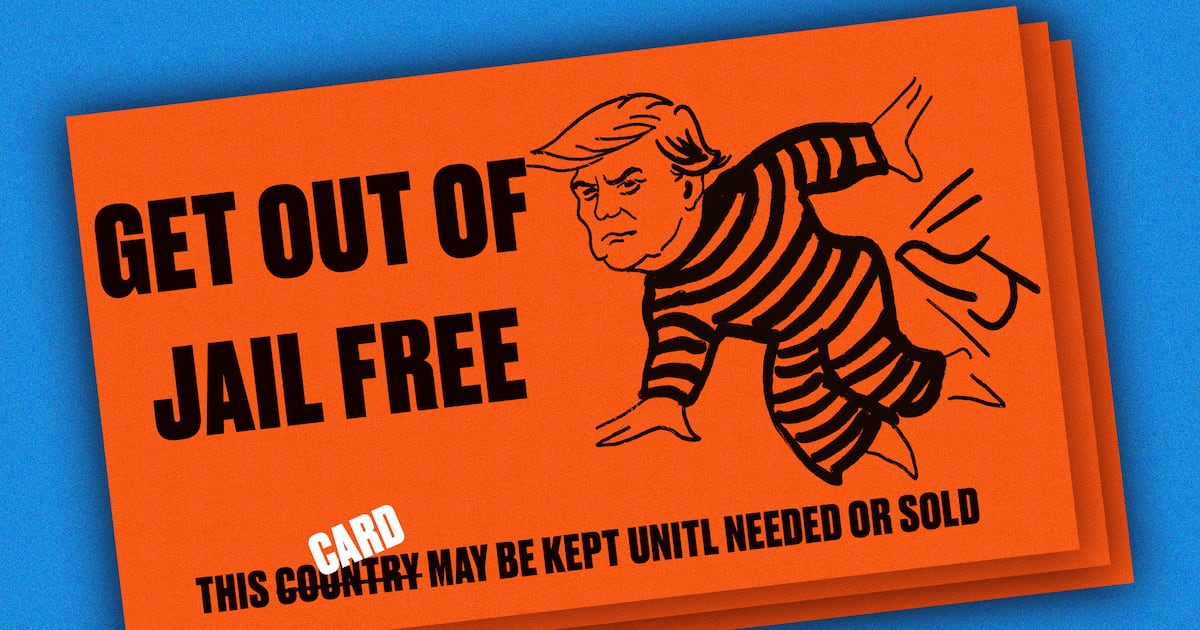

Because the United States government routinely overreacts to (and overestimates the cost of) piracy doesn’t mean that Kim Dotcom is worthy of our support or pity. The gluttonous entrepreneur—whose past transgressions include an insider-trading scandal, selling access to hacked corporate phone and data exchanges, and trafficking in stolen phone cards—wants us to believe that he’s an ordinary businessman, kicking against the pricks, the power-hungry politicians, and the greedy Hollywood executives. Like Assange before him, Dotcom warns gravely that “we are very close to George Orwell's vision becoming a reality,” with the rotund German standing in for the skeletal Winston Smith.

Dotcom understands that if you cloak avarice and illegality in virtue—and fear of American government power—you’ll inherit an army of credulous supporters. Don’t fall for it. He might not be the Internet's Dr. Evil, but neither is he an heir to activists like Aaron Swartz.