There are no winners in T.C. Boyle’s novels, only losers. And they tend not to be the lovable kind either. The Road to Wellville is filled with characters like the strangers you might meet at a Halloween party. They seem charmingly eccentric at first, dressed in their clever costumes, but once they remove their masks and begin to talk, you realize they’re just as petty and miserable as everyone else. And then you learn that they stole their costume ideas anyway. Much of the humor in Boyle’s novels, and much of the tragedy as well, derives from the gasping abyss between his characters’ idealized view of themselves, and the ways they debase themselves at every possible opportunity. This is also the source of their humanity. All of us, like Dr. John Harvey Kellogg in The Road to Wellville, might aspire to act “right and think right through every minute of every day.” But we tend to fail horribly. That failure is what we call life.

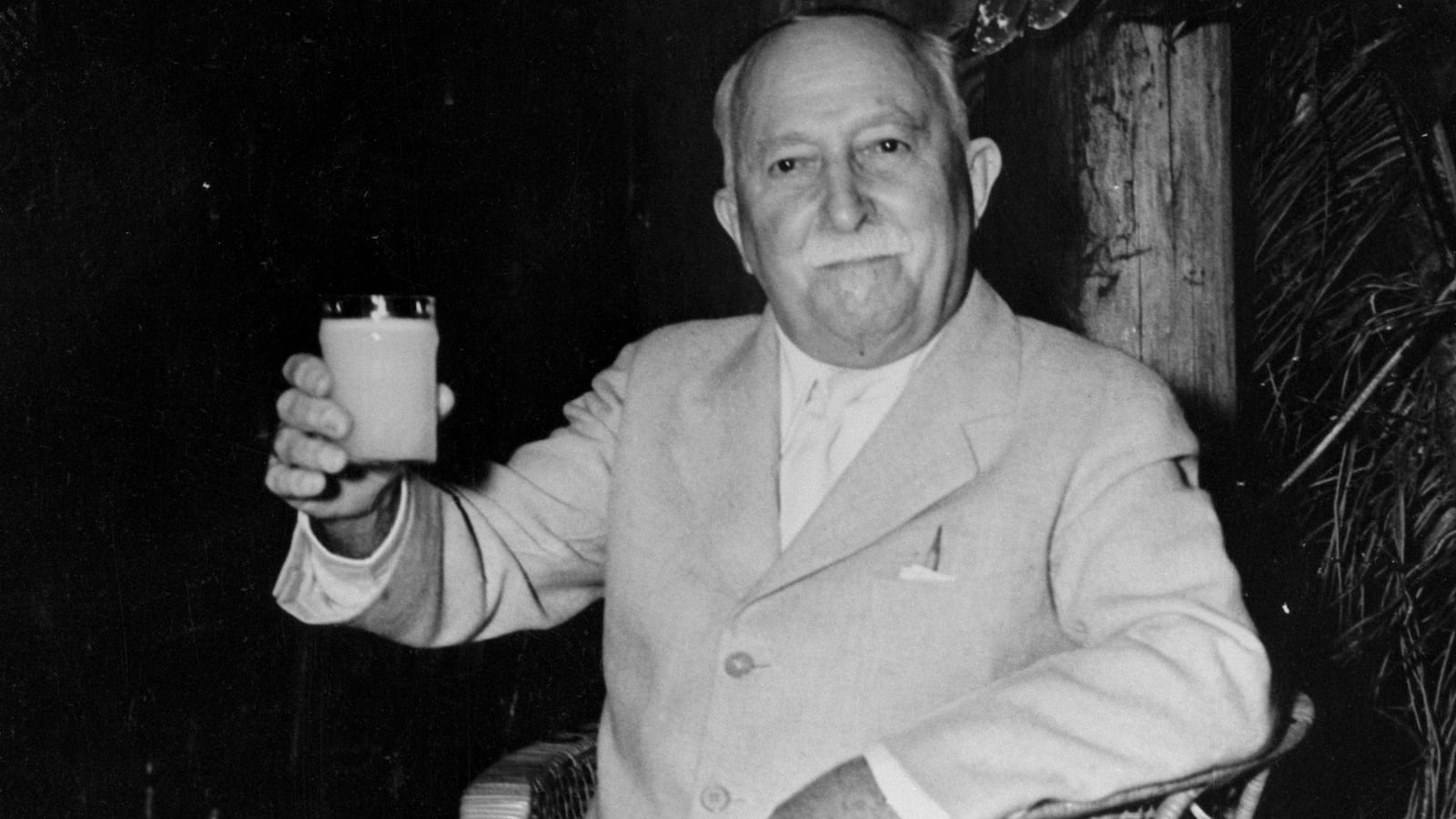

Kellogg is one of Boyle’s great buffoons—and Boyle is a master of buffoonery—but the real Kellogg was nearly as ridiculous. Nutritionist, surgeon, director of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, inventor (he invented the corn flake with his brother, W.K., who profited from the creation by founding the Kellogg Company), and proselytizer for gastrointestinal health, J.H. Kellogg preached the virtues of frequent enemas, vegetarianism, calisthenics, sexual abstinence, hydrotherapy, and plenty of yogurt—yogurt meals and yogurt enemas. He dressed in antiseptic white, “a Santa Claus of health,” with white high-button shoes, white-frame spectacles, a white doctor’s coat, and a preposterously bushy white Van Dyke. The wealthy patients who seek treatment at the San, “the single healthiest spot on the planet,” regard Kellogg as a holy priest, or an even higher power. When Will Lightbody, one of the putative heroes of Boyle’s novel, questions Kellogg’s methods, he is rebuked by a nurse:

“When I think of what he’s done for mankind—for the alimentary canal alone—I have to say, yes, he is a god, my god, and he should be yours, too.”

But Kellogg is a fraud. His weekly homilies rely on phony facts and staged stunts. He forces a patient to submit to radiation therapy, even as it makes her skin slough off her body. In the dead of winter he insists that his patients lie outside in order to enjoy the salutary benefits of fresh air, though he secretly flees to Miami Beach. He is also, in Boyle’s version of events, a murderer. He kills his own son in cold blood (or in a vat of hot macadamia butter, to be specific). Even so, Kellogg comes off better than most of the other characters in The Road to Wellville. Charlie Ossining, a naïve young man who travels to Battle Creek in the hope of making his own fortune on breakfast cereal, loses his entire stake to a con man; but the experience only inspires him to steal, lie, and bilk his own loved ones in turn. Will Lightbody follows his wife Eleanor to the San in a spirit of uxorious duty, only to flail after the first nubile nurse that crosses his path. Eleanor, while adamantly refusing to violate the San’s sexual abstinence policy with her husband, offers her body to a doctor of questionable pedigree, blithely submitting to his “womb manipulation” therapy.

It might have been easy, in 1993, to laugh at the absurd pieties of J.H. Kellogg and his acolytes, but America was then in throes of a cultural rift no less pious, and no less absurd. After Dan Quayle’s speech the previous year excoriating Murphy Brown, a fictional television character, for her decision to have a child outside of marriage, the “family values” debate dominated the national conversation. A furious dispute among social scientists over the value of being raised in a two-family household played out on the opinion pages of the Washington Post and the New York Times. The fact that the new president of the United States was the product of a single-parent home was cited by both sides. 1993 was also the year that William J. Bennett published his bestselling Book of Virtues, a sententious 832-page compendium of instructive “moral stories,” and David Gunn, an OB/GYN doctor, was murdered during an anti-abortion protester outside his Pensacola, Florida clinic. Several months earlier the pro-life organization Operation Rescue had distributed “Most Wanted” posters with Gunn’s picture on it. Randall Terry, Operation Rescue’s leader, embarked on a demagogic national tour that summer, inveighing against feminism and homosexuality. “Hate is good,” he said at an anti-abortion rally in Fort Wayne, five months after Gunn’s murder. “Our goal is a Christian nation. We have a biblical duty, we are called by God, to conquer this country. We don’t want equal time. We don’t want pluralism.”

In 1993 Ralph Reed, the cherubic face of the Christian Coalition, published sanctimonious essays likening the evangelical right to the civil rights movement in the 1960s, while Newt Gingrich, building support in his home state for his incipient Republican Revolution, supported a political resolution censuring homosexuality. Meanwhile he was busy promoting a college course he taught called “Renewing American Civilization,” in which he lamented the “breakdown” of American morality that had occurred during the 1960s. He recorded his lectures, selling them by mail order, and advertised them in speeches made on the House floor, during which he read his toll-free phone number into the Congressional Record.

As we now know, the self-appointed white horsemen of this moral crusade had even more to hide than J.H. Kellogg. In the decade following the publication of the Book of Virtues, Bennett gambled away more than $8 million at casinos in Las Vegas and Atlantic City. Ralph Reed had his own gambling problem—six years later, working for his old friend Jack Abramoff, Reed persuaded his Christian supporters to protest new casinos, in exchange for under-the-table payoffs from Indian casinos anxious to forestall possible competitors. Randall Terry was kicked out of his church after abandoning his wife and children for a younger woman (“Families,” he had warned in a book five years earlier, “are destroyed as a father vents his mid life crisis by abandoning his wife for a ‘younger, prettier model.’”); and his son, who Terry had enlisted in protests against gay marriage, came out in Out magazine. And even as Newt Gingrich was delivering lectures on America’s moral decline, he was being sued for failing to pay alimony to his first wife, and beginning an adulterous affair with Callista Bisek (currently his third wife). His “Renewing American Civilization” lectures were at the center of the ethics investigation that would lead to his resignation from Congress. T.C. Boyle couldn’t have plotted it any better himself.

The moral crusaders of the 1990s were no less sanctimonious, and no less hypocritical than their counterparts in Battle Creek, Michigan nearly a century earlier. They were just much less amusing. A con man is always entertaining, unless it’s you—or your country—that is being conned.

Other notable novels published in 1993:

The Liberty Campaign by Jonathan Dee

Arc D’X by Steve Erickson

The Virgin Suicides By Jeffrey Eugenides

A Frolic of His Own by William Gaddis

A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest J. Gaines

Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang by Joyce Carol Oates

Martin and John by Dale Peck

Operation Wandering Soul by Richard Powers

Operation Shylock: A Confession by Philip Roth

Rameau’s Niece by Cathleen Schine

Butterfly Stories by William Vollmann

Fearless by Rafael Yglesias

Pulitzer Prize:

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler

National Book Award:

The Shipping News by E. Annie Proulx

Bestselling novel of the year:

The Bridges of Madison County by Robert James Waller

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon

1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson

1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis

1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell

1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell

1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin

1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux

1992—Clockers by Richard Price

2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain

1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London

1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather

1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton

1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West

1943—Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles

1953—Junky by William S. Burroughs

1963—The Group by Mary McCarthy

1973—The Princess Bride by William Goldman

1983--Meditations in Green by Stephen Wright