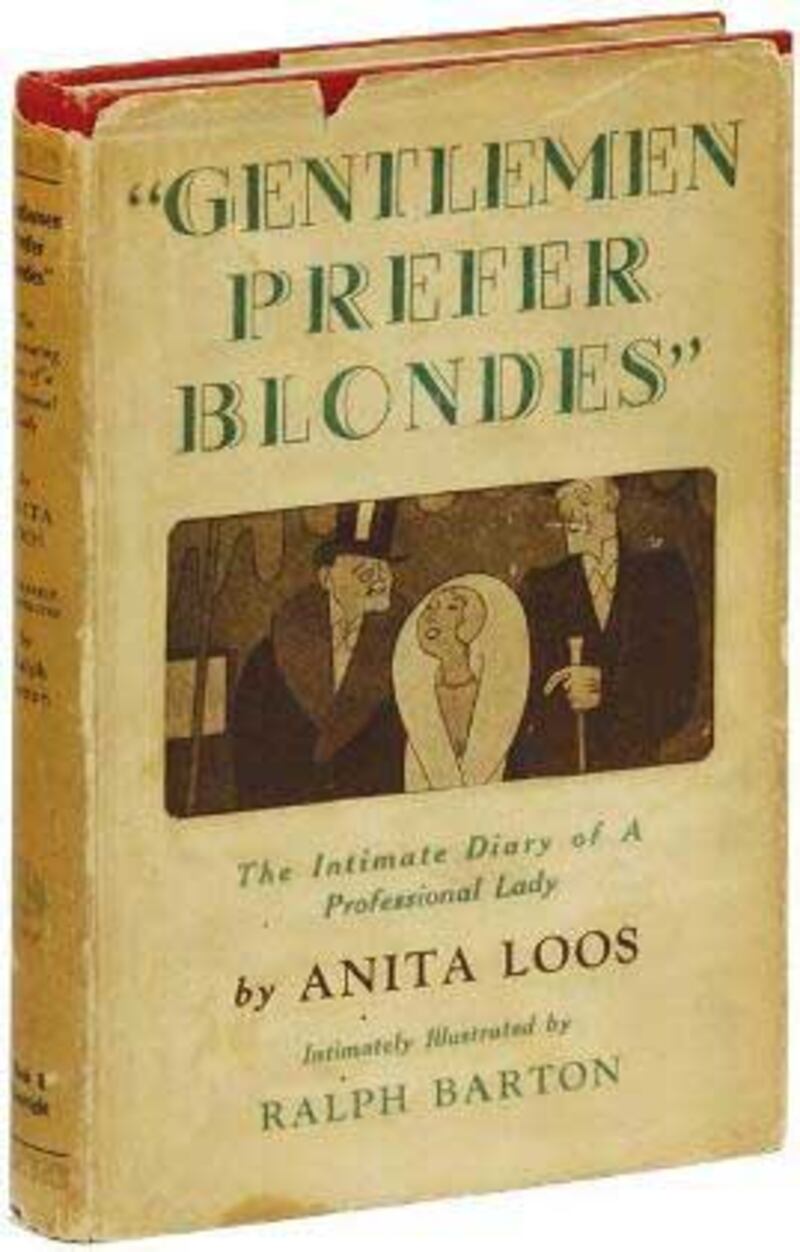

A Philadelphia copywriter named Frances Gerety is credited with coining the phrase, “A Diamond Is Forever” for De Beers in 1947. But a similar phrase served as a punchline more than twenty years earlier, in Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. “Kissing your hand may make you feel very very good,” observes Loos’s narrator, Lorelei Lee, “but a diamond and safire bracelet lasts forever.” It seems right that the line Advertising Age called “the slogan of the century” originated in Anita Loos’s novel. Lorelei Lee at least would have found it most intreeging.

Loos’s premise is deceptively simple. The novel is the diary of a young blonde woman from Little Rock who has recently arrived in New York City. The gentlemen Lorelei meets—many of them titled, most of them married, all of them rich—attack her like flies on honey. They shower her with jewels, believing they will dazzle the country girl into submission, but Lorelei, despite lacking a particularly sophisticated lexicon (having never having attended colledge) outsmarts them all. It’s not that she doesn’t love jewels. She’s obsessed with jewels. It’s just that she knows that the best way to maximize her jewelry collection is to maximize her gentlemen.

From the lobby of the Ritz in New York City, where Lorelei is accustomed to meeting her gentlemen callers for lunch, the novel follows Lorelei and her friend Dorothy on a luxury passage to Europe, all expenses paid by a solicitous button magnate from Chicago (“I really love the Majestic because you would not know it was a ship because it is just like being at the Ritz.”); and later to the London Ritz, the Paris Ritz, and the Budapest Ritz. In London she sees the Tower of London, and in Paris she gets an eyeful of the Eyefull Tower. She dances with the Prince of Wales and is analyzed in Vienna by one Dr. Froyd, but the most intreeging sights of all are the hotel bars where she drinks champagne cocktails and the boutiques where, trailed by magnates, intellectuals, and noblemen, she discovers, to her delight, ever more expensive pieces of jewelry. Most desirable of all is a diamond tiara, which one married suitor acquires for her at the price of $7,500 (about $100,000 in today’s dollars). “I have to admit,” writes Lorelei, “that everything always turns out for the best.”

Going on synopsis alone the novel might appear a silly send-up of a foolish girl and her even more foolish admirers. But the synopsis leaves out the source of the novel’s enormous appeal. And enormous it was: in the first year after publication, it sold about one thousand copies a day in America alone, became a comic strip, a stage play (also written by Loos), and a film (released in 1928, a predecessor by twenty five years to the more famous Marilyn Monroe version; no trace remains). The novel did nearly as well abroad, where it was published in translation in more than a dozen countries, including China and the Soviet Union. The Prince of Wales, who was observed doubled over with laughter while reading it, bought copies for all his friends. The royal physician prescribed it to King George as a cure for melancholia. “It’s so successful I’m scared of it,” Loos told a reporter from the New Yorker. “I’m even afraid of pencils these days.”

The appeal was not merely popular. Edith Wharton called it the “Great American novel”; William Faulkner, in a fawning letter he sent Loos, expressed regret that he hadn’t thought of the idea first; other admirers included E.B. White, Sherwood Anderson, William Empson, and Rose Macauley. It was one of the only books that James Joyce, his eyesight fading, allowed himself to read while taking breaks from Finnegans Wake. Aldous Huxley said that Loos “the only woman in America he wanted to meet.” Arnold Bennett and H.G. Wells took her out to meals when she came to London. George Santayana called Gentlemen Prefer Blondes the best book of philosophy written by an American.

It is an extremely funny book, and has remained funny for more than ninety years—almost definitely a world record. The humor sticks because the satire is not actually directed at Lorelei but at man’s lowest instincts, instincts that during the madly prosperous Twenties were allowed unprecedented indulgence. “I wanted Lorelei to be a symbol of the lowest possible mentality of our nation,” wrote Loos in a forward to the novel’s 1963 edition. The men chasing Lorelei—statesmen, intellectuals, and titans of industry—are no less representative of this mentality. She does not even spare the writer who most forcefully exposed the era’s ludicrous excesses and inanities. Early in the novel Dorothy, the only girl in New York City less “refined” than Lorelei, is pursued by H.L. Mencken, “who really only prints a green magazine which has not even got any pictures in it.” In fact it was Mencken, a mentor to Loos, who inspired the novel in the first place. Loos, bewildered by the sight of so many of her intellectual male friends falling for ditzes, particularly blonde ones, was amazed to see that Mencken was bewitched by “the dumbest blonde of all.”

No character better personifies America during the jazz age than Lorelei Lee—greedy, petty, frivolous, cunning, drunk on champagne. Unlike peers who wrote about the immoderation of Twenties society in a darker vein—writers like Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Dreiser—Loos did not consider the crass materialism or childishness of the age a tragedy. She considered it an absurdity. She considered all human beings, in their essence, to be absurd. Her novel will continue to be funny as long as we remain so.

Other notable novels published in 1925:

Dark Laughter by Sherwood Anderson

The Professor’s House by Willa Cather

Manhattan Transfer by John Dos Passos

An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis

Firecrackers by Carl Van Vechten

Pulitzer Prize:

So Big by Edna Ferber

Bestselling novel of the year:

Soundings by A. Hamilton Gibbs

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2014. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers. — Nathaniel Rich

Previous Selections

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson 1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin 1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux 1992—Clockers by Richard Price 2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain 1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London 1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather 1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton 1933—Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West 1943—Two Serious Ladies by Jane Bowles 1953—Junky by William S. Burroughs 1963—The Group by Mary McCarthy 1973—The Princess Bride by William Goldman 1983—Meditations in Green by Stephen Wright 1993—The Road to Wellville by T.C. Boyle 2003—The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2013—Equilateral by Ken Kalfus 1904—The Golden Bowl by Henry James 1914—Penrod by Booth Tarkington 1924—So Big by Edna Ferber 1934—Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara 1944—Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith 1954—The Bad Seed by William March 1964—Herzog by Saul Bellow1974—Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig1984—Neuromancer by William Gibson1994—The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields2004—The Plot Against America by Philip Roth2014—The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henríquez1905—The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton1915—Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman