Michael Bloomberg knows what’s best for you—no matter what you think you want.

That same ethos has permeated Bloomberg’s time in public service and the private sector, from his his last-minute entry into the most crowded presidential primary in modern history to his functional elimination of smoking in New York City public life. But no single issue defined Bloomberg’s view of his role in the day-to-day lives of citizens more than the highest-profile policy battle of his three-term mayoralty: the so-called “soda ban.”

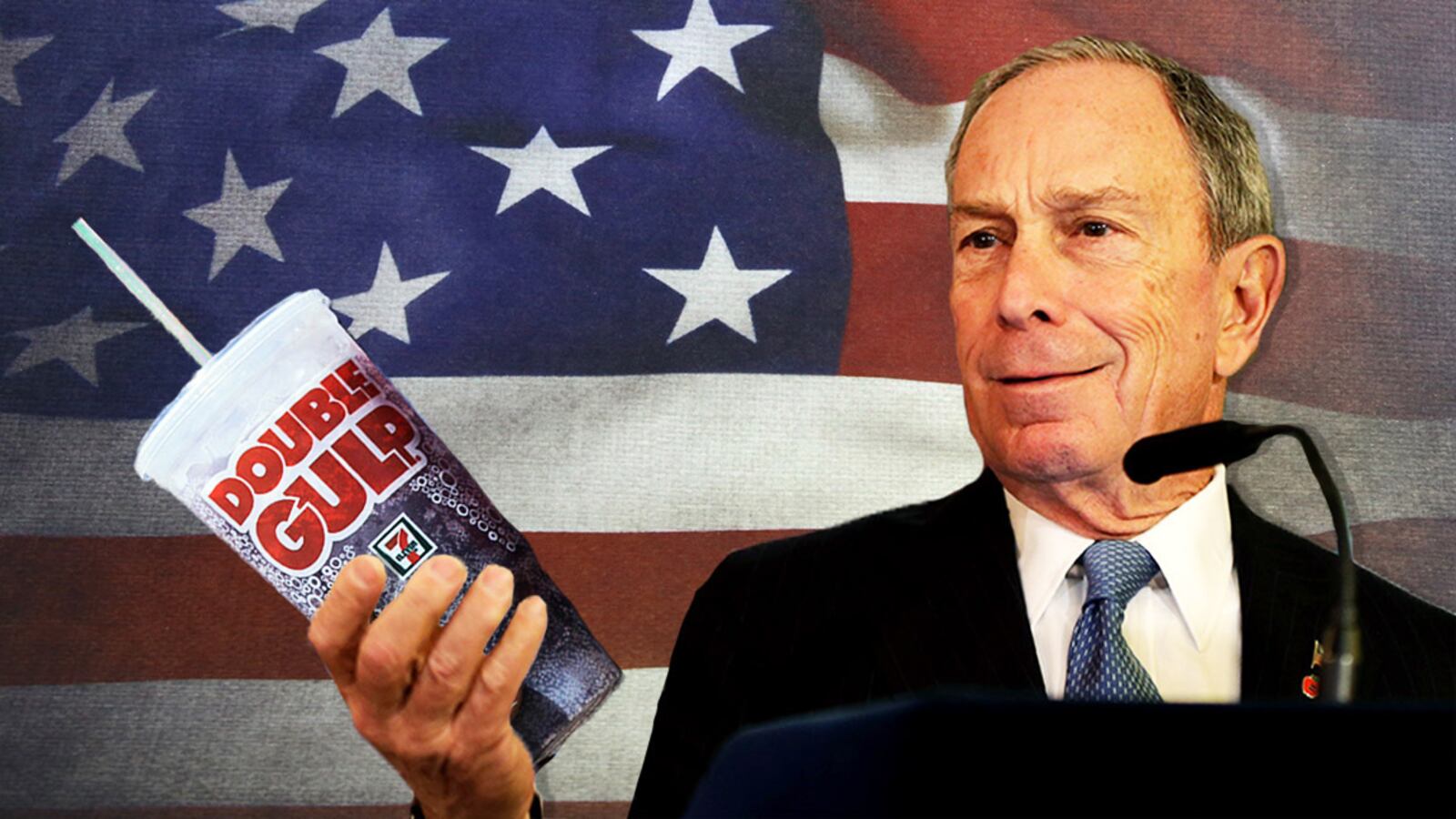

That proposal, which would have prohibited the sale of most sugary drinks more than 16 ounces across the five boroughs, was the issue that first introduced many Americans to Bloomberg—either as a champion of public health fighting corporate influence, or as a busybody billionaire who thinks he knows what’s good for the rest of us. Either way, New York politicos say that the years-long battle over soda is an instructive example of Bloomberg’s view of leadership and public policy.

“I think it falls in line with his image and track record on public health—the most consequential thing he did as mayor was the smoking ban, and there was uproar against it, and then he tried to do soda,” a prominent Democrat in elected office in New York City told The Daily Beast. “People called him the ‘Nanny State Mayor.’”

Bloomberg, whose eponymous financial data and media company has made him one of the richest men in the world, first ran for mayor of New York City on an economic message, telling voters that in the wake of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the city needed a mayor with experience running a business to strengthen its economy.

But shortly after his election, Bloomberg’s first major public policy initiative was a massive expansion of regulations against smoking in restaurants and bars. Those rules kicked off a years-long crusade against perceived dangers to public health, ranging from trans fats and second-hand smoke to the crowning jewel of Bloomberg’s health policy: a multipronged crackdown on sugary drinks.

“Obesity is a nationwide problem, and all over the United States, public health officials are wringing their hands saying, ‘Oh, this is terrible,’” Bloomberg told the New York Times when the rule was first proposed in 2012. “New York City is not about wringing your hands; it’s about doing something. I think that’s what the public wants the mayor to do.”

Under the plan, all restaurants, fast-fooderies, delis, movie theaters, stadiums and food carts would be barred from selling sugary beverages in cups larger than 16 ounces, “sugary beverages” being defined as a drink with more than 25 calories per eight ounces. (Diet sodas, fruit juices, milkshakes and alcoholic beverages were not included, although the status of sugary coffees were a nightmarish open question.)

The proposed restriction on soda size in the city was struck down on the eve of its implementation, with New York Supreme Court Judge Milton Tingling writing in his majority opinion that the rule was “arbitrary and capricious,” and lost on appeal in 2014—but not before Bloomberg’s “soda ban” made him the bête noire of libertarians, minority-owned businesses, and millions of people who just liked soda.

“The New York City health department’s unhealthy obsession with attacking soft drinks pushed them over the top,” Stefan Friedman, spokesperson for the American Beverage Association, which lobbies on behalf of the beverage industry, said at the time the soda ban was first proposed. “These zealous proposals just distract from the hard work that needs to be done on this front.”

Tabloids dubbed him “Nanny Bloomberg,” and failed attempts to both tax sugary drinks and ban the ability of New Yorkers on food stamps to use those benefits to purchase soda infuriated advocates who said that the crackdown disproportionately targeted the wallets of the poor. The NAACP of New York and the Hispanic Federation even joined a lawsuit against the rule, arguing in court filings that the proposal “arbitrarily discriminates against citizens and small-business owners in African-American and Hispanic communities.”

The image of Bloomberg as an avatar of billionaire paternalism may be hard to shake, particularly among laissez-faire centrists who might normally consider supporting a moderate candidate with a business background, political strategist Liz Mair told The Daily Beast.

“The soda ban certainly registered him on the radar of conservatives who are driven mainly by cultural issues,” Mair said. “It also registered him on the radar of hardcore libertarians.”

But with Bloomberg’s newfound identity as a Democrat, Mair noted, that’s less of an issue in a presidential primary.

“I doubt many if any of those voters are in play in 2020 anyway,” Mair said. “I don’t think many of us are voting in either party’s primaries this time around.”

More difficult to explain to progressive voters, one Democratic political consultant told The Daily Beast, is that with the exception of his smoking ban, Bloomberg’s attempts to force New Yorkers into healthier lifestyles failed miserably.

“Rates of obesity and diabetes in New York City actually increased under Bloomberg,” the consultant, who is not affiliated with a rival campaign, told The Daily Beast. “Banning trans fats may have prevented a few heart attacks, but it’s hard to run on something that didn’t happen—you can’t exactly have someone who would have died of a coronary without your trans fats ban introduce you at a rally.”

Bloomberg, for his part, pointed out numerous times during his tenure that the life expectancy of New Yorkers grew at a faster pace than the rest of the country under his reign—and that he wanted to be sure that you remember that his helped.

“Just before you die,” Bloomberg told listeners during a radio address in 2012, “remember you got three extra years.”