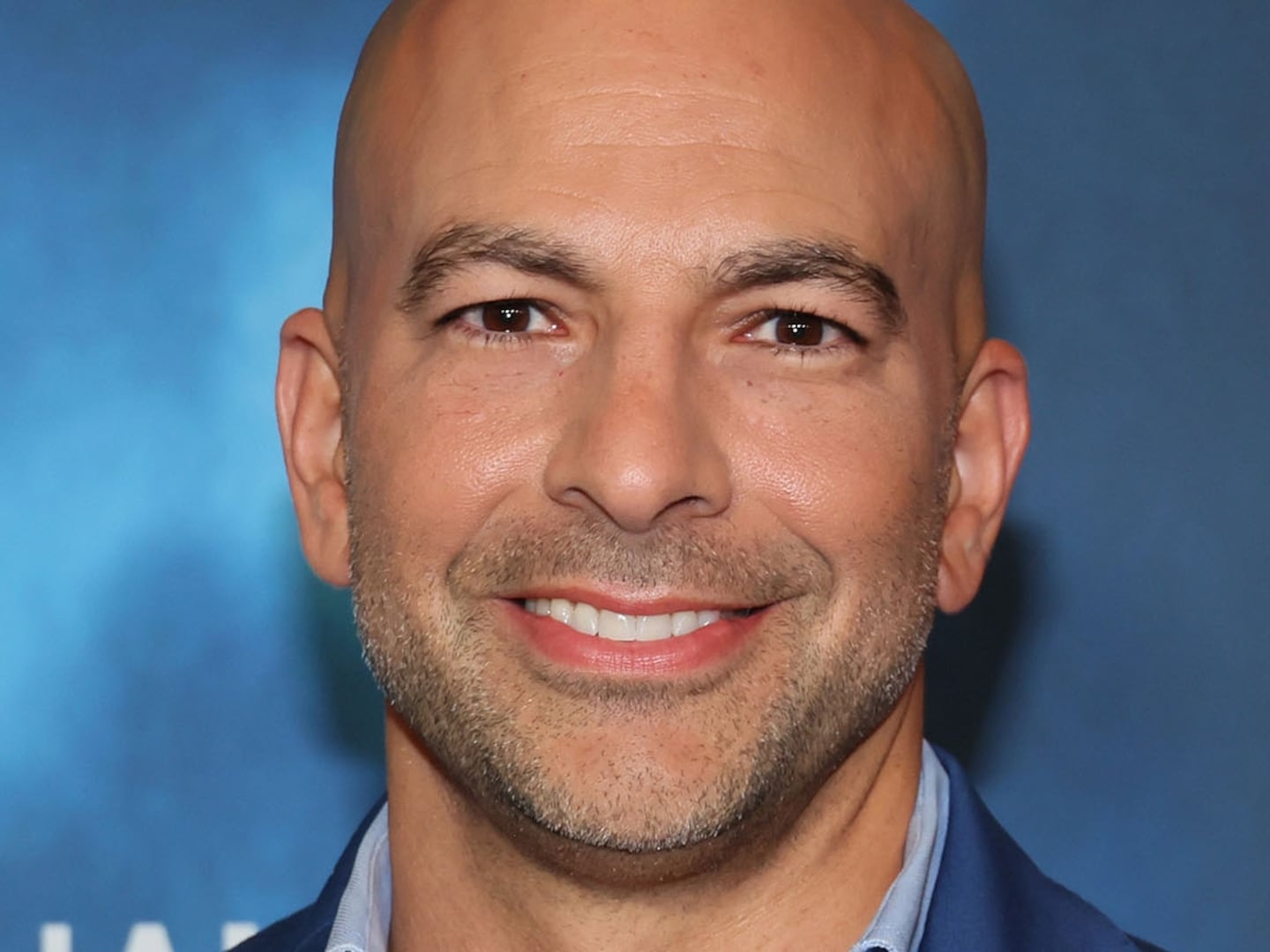

I watched Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech to Congress with a guy named Fadi Quran. He recently graduated from Stanford, where he double-majored in physics and international relations. He lives in Ramallah, where he’s starting an alternative energy company. And he just might rock our world.

Quran is helping to coordinate a raft of Palestinian youth organizations—located in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria—all united around one goal: to create a Palestinian Tahrir Square. They organized the unity march that helped pressure Fatah and Hamas to reconcile. Ten days ago, they organized the Nakba Day protests in which refugees marched on Israel’s borders.

What they’re doing isn’t exactly new. Palestinians in the West Bank have been conducting regular nonviolent protests for many years now, often against the separation barrier that stands between them and their fields. But Egypt and Tunisia made Quran and his colleagues realize that nonviolence was possible on a much larger scale. Not everyone in his movement believes in peaceful resistance as a matter of principle, he admitted sheepishly. But they all believe it represents the right strategy. They’ve been studying the civil rights movement and Gandhi’s struggle against the British and the movement that peacefully brought down Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia. No one wants a second intifada, he insisted. “It hurt us much more than the Israelis.”

When I asked Quran what his movement believes, I expected to hear about borders and refugees and Jerusalem. Instead, he began talking about John Rawls and John Locke, a social contract between the government and the governed. A Palestinian government that denies his rights, he insisted, is as offensive as an Israeli one. When I pressed him on whether his colleagues want two states—one Palestinian, one Jewish—or a secular binational one, he seemed strangely agnostic. He said that in an ideal world one democratic state would be better, before adding that of course such a state would have to guarantee the safety and cultural autonomy of Jews. (One of his inspirations, he said, was Martin Buber, the Jewish philosopher who advocated a binational state in the 1920s and 1930s). When I said I didn’t consider a binational state very realistic, he conceded the point, before noting that in the age of Netanyahu and Lieberman, most Palestinians don’t consider a two-state solution very realistic either.

After a while, it hit me: This is what Israelis and American Jews have been demanding all along. Didn’t we always say, during the bloody Arafat years, that when the Palestinians produced Gandhis everything would change? We’d never be able to resist; our Jewish hearts would melt. Now that it’s starting to happen, I suspect the response will be exactly the opposite: Yes, there’s something admirable about young people like Fadi Quran, but who are they kidding. This is the Middle East, not Palo Alto. It’s no place for dreamers; they’ll get eaten for lunch.

Privately, many in Congress consider settlement expansion a catastrophe and the occupation a disgrace.

Maybe so. But watching over Fadi’s shoulder as members of Congress robotically rose to applaud Netanyahu, I couldn’t help thinking of the contrast. Anyone who has spent any time around Congress knows that many of the people who applauded Netanyahu—the Jewish Democrats in particular—don’t actually support his policies. Privately, many consider settlement expansion a catastrophe and the occupation a disgrace. But they don’t want to create headaches for themselves. Could they say what they really believe and get reelected? Probably—after all, incumbents are very hard to beat. But who needs the hassle?

“What we want to do next,” Fadi added, “is freedom rides, like in the South. We’ll board settler-only buses and make them arrest us or beat us up.” He mentioned that many American Jews had participated in the civil rights movement. “So how will American Jews react if we do this,” he asked? “Do you think we’ll get any support, given your history?” I started to talk about the way American Jewish politics actually works, about the gap between what people believe and what they say, about the way people wall themselves off from unpleasant realities, and then I stopped. It was too depressing to explain. Fadi Quran has the right to dream.

Peter Beinart, senior political writer for The Daily Beast, is associate professor of journalism and political science at City University of New York and a senior fellow at the New America Foundation. His new book, The Icarus Syndrome: A History of American Hubris, is now available from HarperCollins. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook.