New body-camera footage shown Tuesday to the family of Andrew Brown Jr. showed sheriff’s deputies “standing on the pavement unloading their weapons” on the 42-year-old Black man as he tried to drive away, the family’s lawyers said Tuesday.

The family and one member of their legal team were able to view 19 minutes of about two hours of body-camera footage taken during the April 21 incident. The six new videos included snippets from different body cameras and dash footage. Previously, they’d only been shown about 20 seconds of edited footage, but a North Carolina judge ruled on April 28 that they could see more footage.

“At no point did we see Mr. Brown pose a threat to the law enforcement that was there. It was absolutely and unequivocally unjustified,” Chance Lynch, one of the Brown family lawyers, said during a press conference after viewing the extended footage.

The description of the new footage corroborates what Chanel Lassiter, another family attorney, said two weeks ago after viewing the original snippet. At the time, Lassiter said that Brown’s hands were on the steering wheel when authorities opened fire—and that he tried to drive away to “evade being shot” before crashing into a tree.

Brown was shot at about 8:30 a.m. while deputies were serving a search warrant and arrest warrant at his house in Elizabeth City on felony drug charges. The Pasquotank County Sheriff’s Department released almost no details about the incident for days and, due to North Carolina laws, were unable to release the body-cam footage without a judge’s order.

But during a hearing last month about releasing the footage, Pasquotank County District Attorney Andrew Womble insisted that the footage showed that Brown's car moved and “made contact with law enforcement” twice before deputies opened fire.

Lynch said on Tuesday that Brown was in his car and appeared to be on the phone when he was “ambushed” by the officers. He said he believed that “at no point” did Brown see the seven deputies initially approach his car.

While he did not go into details about what prompted the initial shot, Lynch said the gunfire prompted Brown to “put the car in reverse, putting several feet, if not yards, away from the police who were there” before he turned his steering wheel to the left to drive away. At all times, Lynch noted, Brown’s “hands were visible.”

“At no point did we ever see any police officer behind his vehicle. At no point did we ever see Mr. Brown make contact with law enforcement,” Lynch said, adding that Brown was apparently trying to leave the scene as officers were unloading their weapons. “We did not see any actions on Mr. Brown’s part that he made contact with them or tried to go in their direction. In fact, he did the opposite. While there was a group of law enforcement were in front of him, he went in the opposite direction.”

Lynch said that the “final shot” to Brown’s head made him “lose control...and collide with a tree.” But there were at least six “bullet holes in the passenger side of his car,” he added. The “windows were shattered” and at least one bullet even went through the front windshield, he said.

He said that after deputies pulled Brown out of the car and laid him “face-first flat on the ground” and checked on the fatal bullet wound, they “begin to search his home.”

“The video I saw [two weeks ago] was pretty much the same as what I saw today. Just a few more details. He wasn’t in the wrong at all. What’s in the dark will come to the light,” Khalil Ferebee, one of Brown’s sons, said Tuesday. “We will get justice.”

Attorneys for Brown’s family have previously asked Womble to recuse himself because of his ties to the sheriff’s department and to ensure “fairness, transparency, and pursuit of the ends of justice.”

“We do not believe we will have a fair set of eyes looking at this going forward,” Bakari Sellers, another attorney, said Tuesday. He said that while the family were not shown the full two hours of footage from the incident, they believe what was shown today “tells the entire story of what happened to Andrew Brown Jr.”

An independent autopsy commissioned by the family’s lawyers concluded that Brown was shot at least five times in his car—including one “kill shot to the back of the head” while his hands were on the steering wheel. The autopsy, performed by Dr. Brent Hall, showed that while Brown sustained four bullet wounds to his right arm, the fatal shot penetrated his brain and skull and never exited his head.

Pasquotank Chief Deputy Daniel Fogg said that the arrest warrant operation was classified as “high-risk” because Brown was a convicted felon with a history of resisting arrest. The search warrant, first obtained by WAVY, revealed that Brown was being watched for over a year and had allegedly sold drugs to an informant. Court records show that Brown had a history of criminal charges since the 1990s, including a misdemeanor drug-possession conviction and at least two pending felony drug charges.

However, Brown’s family has said no drugs or weapons were seized from the 42-year-old’s property or car, according to Harry Daniels, one of their lawyers.

Three of the seven officers—Investigator Daniel Meads, Deputy Sheriff II Robert Morgan, and Corp. Aaron Lewellyn—fired their weapons during the incident and are on administrative leave. The four other deputies—Lt. Steve Judd; Sgt. Michael Swindell; Sgt. Kendall Bishop; and Sgt. Joel Lunsford—were cleared after a follow-up investigation.

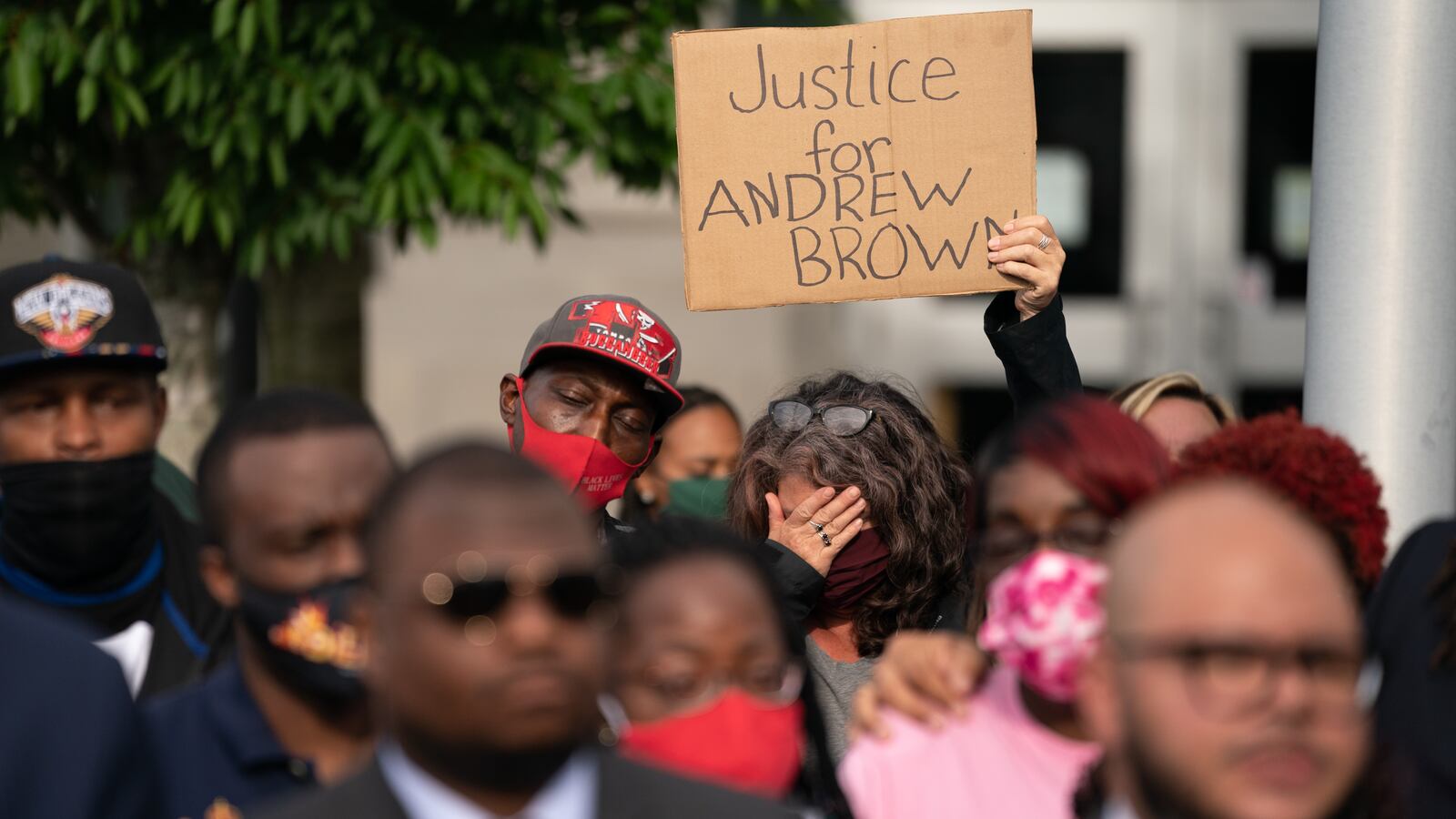

The shooting, just hours after a Minneapolis jury found ex-cop Derek Chauvin guilty of murdering George Floyd, prompted hundreds of North Carolinians to take to the streets in protest.

The FBI also opened a federal civil rights investigation into the incident death while North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper called for a special prosecutor to be appointed “to help assure the community” and Brown’s family that a “decision on pursuing criminal charges is conducted without bias.”

The release of body-camera footage comes after weeks of legal hurdles put up by the state, city, and local law-enforcement officials. Under North Carolina law, body-camera footage cannot be released unless there is a court order because it is not considered to be a public record.

While the judge ruled on April 28 that Brown’s family could see the footage, he said the public would have to wait at least 30 days in order to allow authorities to pursue criminal charges.