Knife Fights: A Memoir of Modern War and Theory and Practice is a provocative and engaging book by a soldier-scholar who played a crucial role in reviving counterinsurgency in the American military at a time (2004-2008) when the Powers that Be did not especially want it revived, despite the nation’s deep involvement in two insurgencies it appeared to be losing. Much has been written about this subject—and, indeed, about this author—elsewhere, but Nagl’s memoir offers at one and the same time arresting new insights into the saga of counterinsurgency’s adaptation in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a very sound, approachable overview of the doctrine’s constituent parts.

It’s very hard to read this book and not come to like Lt. Col. John Nagl. He is clearly an ambitious and hard-driving guy, but he is also self-deprecating and unfailingly respectful of his intellectual adversaries inside and outside the Army. As to the seriousness of his devotion to serving his country, and especially his fellow men and women in arms, there can be no doubt.

Among America’s military services, only the Marine Corps—which declares its deadliest weapon to be the individual Marine armed with his (or her) rifle—has been truly comfortable fighting small wars, insurgencies, and what many defense analysts of the ’90s came to refer to as “operations other than war,” meaning peacekeeping and humanitarian missions. The “big three” services, but especially the Army, have long exhibited a predilection for staying clear of brushfire operations in favor of waging conventional wars, where America’s cutting-edge technology and lethal firepower give them truly decisive advantages.

What’s so bad about fighting “asymmetric wars” against guerrillas and terrorist cells in failed and failing nation states? The short answer: they bring into play political, social, and diplomatic complications not normally associated with conventional fighting.

Population security and social stability—rather than annihilation of enemy forces—are the primary objectives of counterinsurgency campaigns. As a result, field commanders find that in planning and executing those campaigns, they must take into account the views and interests of local government authorities, as well as those of the U.S. State Department and various NGOs, for they, too, play crucial roles in developing and executing broad strategy.

Even worse from the point of view of commanders hungry for quick results, insurgents can dictate the pace and intensity of military operations by withdrawing to sanctuaries and concentrating on propaganda and recruiting activity. And ultimate success, as Nagl reminds us again and again, always rests on the long-term performance of local security forces and the responsiveness of their government, not on the Americans who must train and equip and support their efforts. And so it is that counterinsurgency operations are invariably just as Lawrence of Arabia described them: “messy and slow, like eating soup with a knife.”

The American military learned all this the hard way in Vietnam, where a resilient and disciplined insurgency waged a successful protracted war against the Americans and their feckless allies in Saigon. U.S. ground forces were able to win all the major battles, but their heavy reliance on highly destructive “search and destroy” missions, coupled with American backing of corrupt and faction-ridden allies in Saigon, alienated the very population they were intended to “save.”

Meanwhile, the Communists were able to build and protect a shadow political infrastructure over much of South Vietnam, as they waited patiently for the Americans to grow tired of fighting a costly and inconclusive war. This they did, and after the American military’s departure in 1973, the rickety and corrupt regime in Saigon never had a prayer.

America’s traumatic defeat in Vietnam had a devastating effect on the military. A bright and dedicated group of captains, majors, and lieutenant colonels who had survived the war worked with friends on Capitol Hill and retired senior officers to revitalize and rebuild broken institutions into the most lethal military machine in world history. Never again would American soldiers be bogged down in an unpopular, murky insurgency—or so went the thinking at the time.

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1990, Colin Powell, was one of those men. He lent his name to the new “Powell Doctrine,” meant to determine when and where U.S. forces intervened, which was fully endorsed by the Bush administration at the time. The U.S. military would only be deployed when a vital U.S. interest was at stake, only with maximum force to get the job done quickly, and when a clear objective and exit strategy had been established, and when the people fully supported the mission.

Operation Desert Storm, designed to eject Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, fit the bill on all counts. Lt. John Nagl experienced his baptism of fire commanding an Abrams tank in the 100-hour ground campaign of Desert Storm, and a heady experience it proved to be for a young West Pointer who’d just spent two years earning an MPhil at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar in international relations—and drinking lots of lukewarm beer.

In the ’90s Nagl, like other promising officers earmarked for senior leadership in the Army, studied the “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA) wrought by cutting-edge information and communications technology. According to the RMA’s many disciples, writes scholar Lawrence Freedman, U.S. forces could move “with greater speed and precision over longer ranges than was possible for the enemy; disorienting as much as destroying; attacking only when necessary …” The RMA “played to U.S. strengths: it could be capital rather than labor intensive; it reflected a preference for outsmarting opponents; it avoided excessive casualties … and it conveyed an aura of effortless superiority.”

Politicians like George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld, convinced that international affairs had entered into an era of “American primacy” after the fall of the Soviet Union, embraced the RMA uncritically. Our forces were so lethal, so superior to those of any foe, that they could do just about anything.

Nagl, however, was skeptical about all the fuss over this RMA business and its relevance to future threats to national security. So skeptical, in fact, that he wrangled himself a two-year leave from the Army to return to Oxford, where he wrote a doctoral thesis comparing two counterinsurgencies: one in Vietnam, where the Americans failed, and the other in Malaya, where the British succeeded.

He was “convinced ... that in fights to come we were far more likely to fight insurgents and guerrillas in cities than in tanks in open deserts. The rest of the world had seen the ease with which America’s conventional military forces cut through the Iraqi military. They would have to be crazy to fight us that way again. I therefore resolved to write my doctoral dissertation on … the kind of war that I though was the most likely emerging challenge for American troops. The more I learned, the more I realized that it was also in many ways the most dangerous war that the U.S. military could face.”

When al Qaeda launched the 9/11 attacks, an incensed Bush administration rapidly fashioned a shoot-from-the-hip response that was emotionally satisfying but staggeringly naive. Assisted by its allies, the U.S. military juggernaut would topple the bad guys, first al Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, and then a bit later, Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Then, as if by magic, the Afghans and the Iraqis, liberated from the yoke of oppression, were supposed to come together, eschew Muslim fundamentalism and internal political schisms, and transform themselves into pro-Western, stable states.

Certainly an international aid program would be required to help, but as President Bush made clear time and time again, the United States was not about to get bogged down in any Vietnam-style counterinsurgency. And yet, when Lt. Col. Nagl returned to combat operations in the “wild west” of Al Anbar Province, Iraq, in the fall of 2003, that’s exactly where he found himself:

We were completely unprepared for the war we were about to fight. Our soldiers were tankers, trained and equipped to close with and destroy the other enemy armored units. We had to learn to wage war against an insurgency … we had no training in developing an intelligence portfolio on individual insurgency, conducting security patrols to drive local intelligence, developing local governing councils, training and equipping local police forces, conducting raids to capture or kill high-value targets … Now we struggled mightily to find our enemy, who killed us from the shadows even as we struggled to build political and military entities that could earn the trust and support of the Iraqi people . . . Integrating and prioritizing all these tasks was far and away the most difficult thing I’d ever done, leading me to conclude that while Desert Storm had provided an undergraduate education in warfare, this was graduate school, and I was failing.

Nagl had published a book based on his doctoral thesis in 2002 to little fanfare. But that all changed fast after The New York Times Magazine published a 2004 profile entitled “Professor Nagl’s War,” by Peter Maas, a journalist who was imbedded with Nagl’s unit in Iraq and become deeply impressed by the articulate Army lieutenant colonel fighting in a kind of war he had only learned about in books. Thanks to Newt Gingrich’s efforts, the prestigious University of Chicago published Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam in paperback, and the book was soon being read all over Washington.

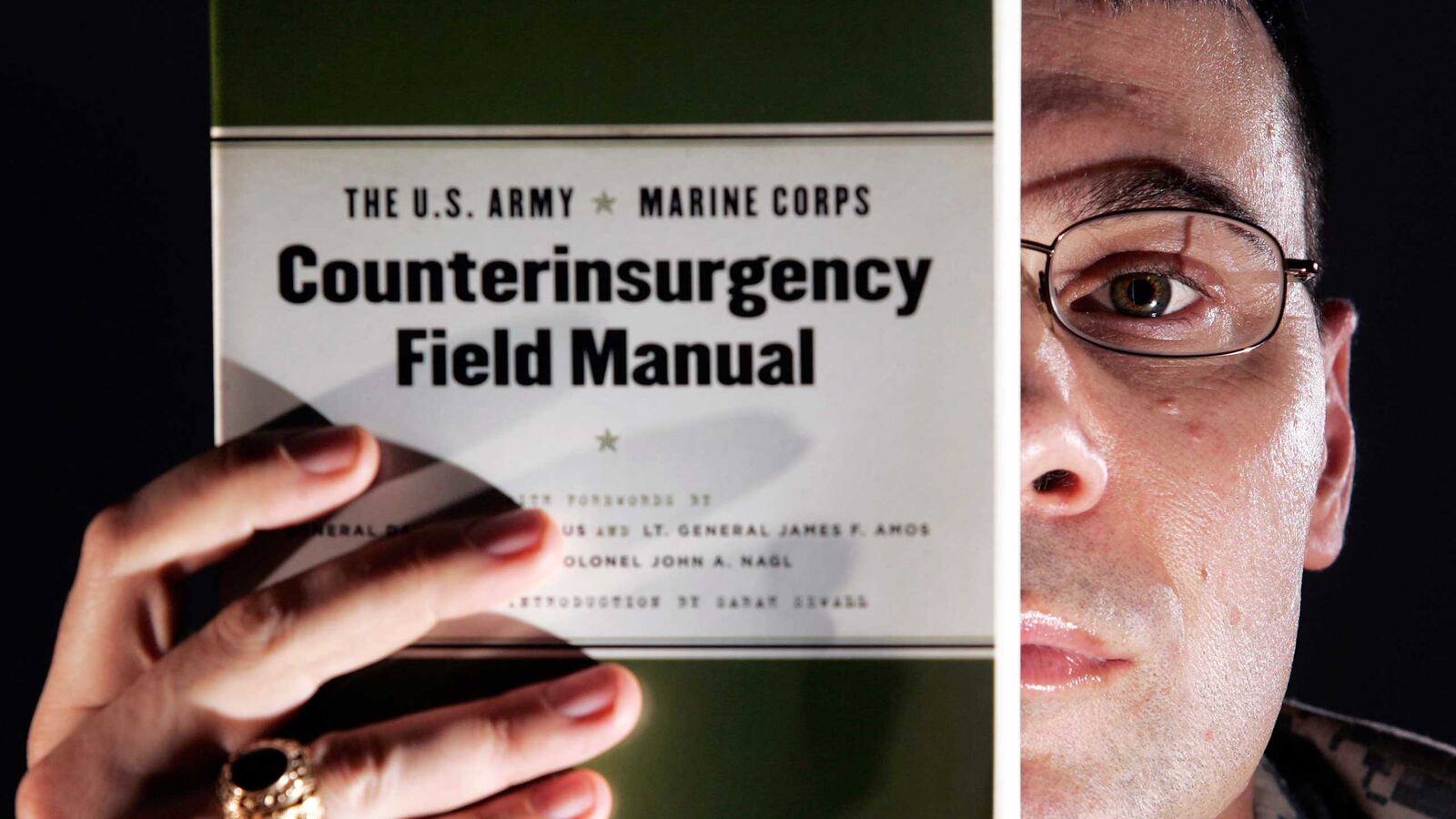

Back from the rigors of a year-long tour in Iraq, Nagl found himself taken under the wing of the Army senior leadership’s fastest rising star, General David Patraeus, a counterinsurgency expert in his own right who was determined to rewrite the book on Army/Marine counterinsurgency doctrine, and put that doctrine to use pronto in the field in Iraq, which was then on the verge of imploding. Nagl became a prominent part of the team of “COINdanistas” who both wrote and critiqued subsequent drafts of the new Counterinsurgency Field Manual.

When Petraeus returned to Baghdad as new commander of American forces to implement both the surge and the adaptation of counterinsurgency tactics in early 2007, Nagl, at Patreaus’s request, served as “his surrogate” to explain and defend the newly published Manual to the American people.

Knife Fight’s final two chapters are not really part of the memoir per se, but a venue for Nagle, now a well-respected defense analyst, to offer his considered reflections on the triple perils of failing to prepare for insurgencies sufficiently, engaging in them with flagging domestic will and support, or failing to engage in them at all.

After years of neglect, Nagl sees the counterinsurgency effort in Afghanistan as having decidedly mixed results, thanks to insurgent sanctuaries in Pakistan, insufficient Afghan human capital, and the lack of adequate governance. The surge in Iraq clearly averted disaster, but long-run success depends upon long-term international support and the commitment of the Iraqis themselves.

“The question is not whether classic counterinsurgency principles of clear, hold, and build work,” observes Nagl toward the end of the book. “The fact that they do has been demonstrated repeatedly. The question is whether the extraordinary investment in time, blood, and treasure required to make them work is worth the cost. The answer to that question depends on the value of long-term stability in the country afflicted by an insurgency, and the answer varies by time and place.”