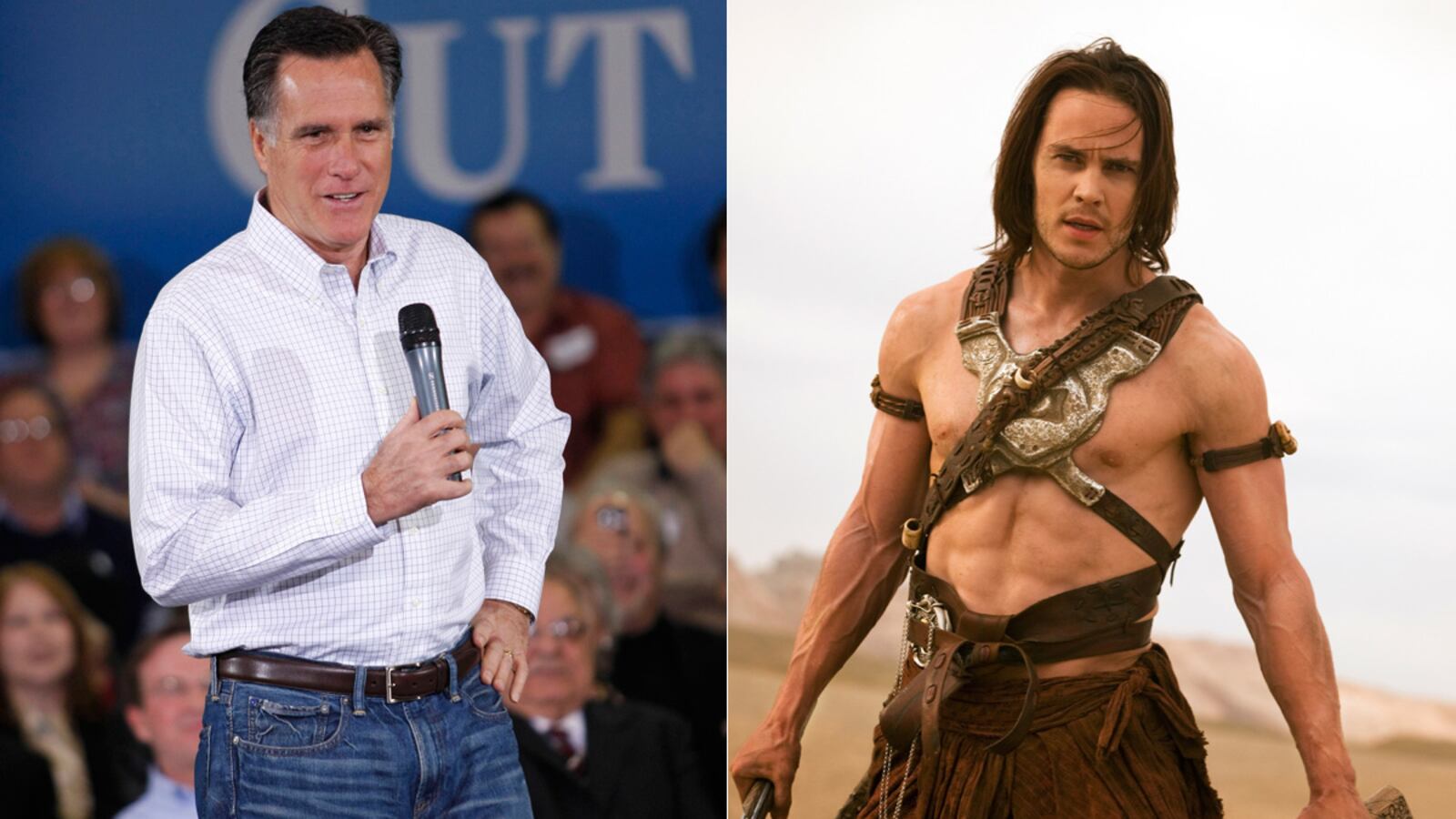

When the media herd heaps premature ridicule on some presumed epic failure, they’ll seldom reconsider the available evidence and admit that they’ve been wrong. Just ask John Carter—and Mitt Romney.

John Carter, an expensive Disney sci-fi spectacular released March 9, provoked gleefully hostile comments from prominent press outlets that seemed to celebrate the film’s disastrous reception. A headline from NBC New York asked, “Was ‘John Carter’ the Biggest Flop Ever?” while Fox News proclaimed that “$250 million ‘John Carter’ Bombs at Box Office.” Entertainment reporters giddily compared the project to other notorious disasters like Heaven’s Gate—a bloated 1980 Western immortalized in a 1984 bestseller I co-authored with my brother Harry Medved called The Hollywood Hall of Shame: The Most Expensive Flops in Movie History.

A New York Times report on John Carter’s purportedly catastrophic debut referenced another multimegaton bomb in its catchy headline: “‘Ishtar’ Lands on Mars.” The Journal of Record compared the new Disney release about a Civil War veteran who flees Apaches and finds himself magically transported to the Red Planet with the 1987 humiliation inflicted on Dustin Hoffman and Warren Beatty for their wretched comedy about talentless rock musicians forced into a high-risk adventure in North Africa. Reporter Brooks Barnes acknowledged that John Carter “had suffered months of ridicule on the Internet and had taken on a funereal aura” even before its Los Angeles debut. Rich Ross, chairman of Disney Studios, told Variety: “I’ve never had something healthy get treated like a corpse.” As if to confirm his pronouncement, The Detroit News ran a prerelease headline proclaiming: “‘John Carter’ Set to Bomb Big.”

But how big did it really bomb?

Actually, the box-office returns in the U.S. and Canada looked respectable if unspectacular, while the overseas grosses far exceeded expectations. John Carter, which cost a reported $350 million to make and market, earned $30.6 million in domestic ticket sales, with a weekend per-screen average of more than $8,000, which earned second place behind the smash-hit Dr. Seuss animated film The Lorax. In Europe, Latin America, and Asia, the movie did much better—drawing an impressive $70 million before even opening in China and Japan, two of the world’s biggest markets. Despite the ridicule from American media, John Carter racked up the fourth-biggest Russian opening of all time.

Within five days of the film’s release, dissenting voices began to challenge the conventional wisdom that the film would lose major money for the Disney Co. The Hollywood Reporter cited Tony Wible, a veteran analyst for Janney Montgomery Scott, who projected that the most likely write-down for the picture would be $53 million—far, far less than Wall Street initially had feared—and even calculated a “best-case scenario” in which the movie earned more than $50 million in profit. Robert Levin in The Atlantic similarly insisted that “‘John Carter’ Did Not Bomb,” noting the boffo overseas business and the encouraging B+ CinemaScore rating from filmgoers—suggesting that positive word of mouth could sustain brisk business in the U.S. and Canada. In fact, the Monday-through-Thursday take brought an additional $9 million in North America, the sort of unexpectedly solid performance that indicates that the film’s second weekend take might not prove as cataclysmic as giddy naysayers easily assumed.

Meanwhile, audiences and many critics seemed to enjoy the picture, defying the prerelease assumptions of its awful quality. The Rotten Tomatoes website showed a very slight majority of reviewers who recommended the movie (96 positive reviews against 91 negative), while civilian filmgoers delivered a good-but-not-great rating of 3.7 (of 5). A.O. Scott of The New York Times considered the movie “colorful and kind of fun,” while NPR liked its “utterly immersive and lifelike characters.” For the record, I also enjoyed the film and reviewed it positively as a campy, energetic, go-for-broke hoot, irresistibly unembarrassed by its own silliness.

Nevertheless, the conventional wisdom remains all but unshaken by decent box-office performance and many favorable reviews, keeping faith with the snickering narrative selected by most pundits before they’d even seen the picture. Concerning John Carter and many other heavily hyped but suspect projects, the most influential masters of the media embrace the time-honored mantra: “That’s our story, and we’re sticking to it.”

The same questionable approach characterizes analysis of Mitt Romney’s campaign, where major media refuse to accept new evidence and double-down on their initially dismissive reaction. Everyone who follows politics knows the tired litany: the former Massachusetts governor is too stiff, too plastic, too patrician, too inconsistent to win the presidency. As a multimillionaire Mormon, he can’t connect with ordinary people and will never appeal to “born again” Christians. He may win the GOP nomination by default, but he’s inspired no real enthusiasm from the party’s rank and file and will lose in a landslide to Obama.

For me, personal experience exploded those assumptions March 3, when I introduced Romney to a wildly enthusiastic rally near my Seattle home the day before the Washington state caucuses. More than 2,000 people showed up at a community center in Bellevue on a damp, frosty Friday morning at 8 a.m., lining up as much as two hours in advance, overflowing the assigned room and then jamming into another hall to listen to the proceedings through loudspeakers. The reputedly bland Romney seemed energized by the early-morning mobs, leaping up on the stage to delight the overflow crowd, speaking with passion and, dare I say it, crackling charisma. The response proved deafening, electrifying, exhausting—displaying the kind of intensity and emotion I had last seen as a young volunteer in the Bobby Kennedy campaign of 1968 (no, I’m not kidding).

Of course, the press barely reported on this event—despite the presence of camera crews from CNN and other major networks—because it didn’t fit their narrative of Romney as the pathetic, unloved Daddy Warbucks trying to buy affection he couldn’t earn any other way. The media also largely ignored the next day’s Washington state caucuses, where turnout exceeded 2008’s numbers fourfold (no, that’s not an exaggeration) and Romney crushed Santorum, 38 percent to 24 percent.

Similarly, the reporting on the primaries and caucuses of March 13 ignored all evidence of energy on Romney’s behalf. In the Hawaii caucuses, Mitt mauled Santorum 45 percent to 25 percent, with turnout setting state records. Even in Alabama and Mississippi, where experts initially declared that the Yankee governor stood no chance of victory, he tied Gingrich (in Newt’s home region) in percentage terms in both states, while earning a near tie with both Santorum and Gingrich among “born again” Christian voters in Mississippi, despite presumed anti-Mormon prejudice. Meanwhile, after all the relentless battering of the GOP frontrunner from both his intraparty rivals and most of the media, he remains surprisingly competitive with President Obama. According to the Real Clear Politics average of all the latest trial-heat polls (as of Friday), Romney draws within 4 percentage points of the incumbent—just outside the margin of error.

The media consensus discounts any evidence of Romney’s progress for the same reason it dismisses all indications of John Carter’s success: in both cases, it cost such huge piles of money to achieve even the most dubious triumphs. It’s instinctive for entertainment as well political reporters to look askance at the most lavishly funded competitors and to favor scrappy, low-budget upstarts.

But this inevitable bias shouldn’t produce inaccurate scorecards or shape unreliable predictions. John Carter, like the Mitt Romney candidacy, may be clunky and clumsy and campy, requiring untold millions to compete successfully. But both contenders, as imperfect as they may be, stand a good chance of final victory.