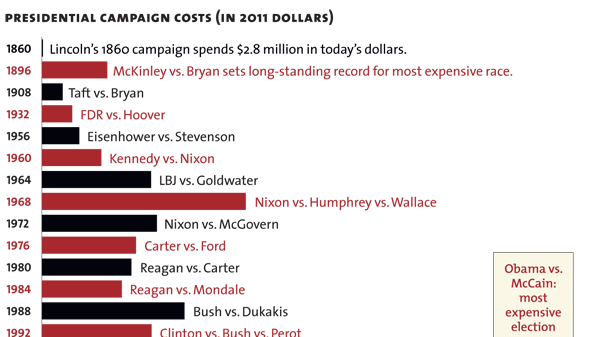

Have you seen this chart?

I was fascinated when it began to make the Internet rounds, for this reason: we know surprisingly little about presidential campaign expenditure before enactment of the post-Watergate campaign finance laws in 1974, and virtually nothing about presidential campaign expenditure before the passage of the first federal campaign disclosure laws in 1925.

For the elections of 1928-1972, there are records of large-dollar donations to presidential nominees, but no record of spending on nomination fights, and no very clear idea of total amounts spent.

So where'd the numbers below come from? Many commentators cite George Thayer's 1973 book, Shaking the Money Tree as a source for older campaign spending. I found a used library copy of the book and read it yesterday on a plane flight to Vancouver. As a compendium of reported and estimated information on the campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s, Shaking the Money Tree is helpful, as best I can judge.

But for the period before 1925, the book has a strong feeling of Herbert Asbury's Gangs of New York: it's a compendium of anecdotes, which may or may not be true, none of them footnoted, supported only by a thin bibliography at the end.

One more point: people who look at charges like the below risk being seriously misled if they don't appreciate that 19th century American politics was financed in a radically different way than 20th century politics. Until the 1880s, the most important source of party funding was not donations, but a kickback on the salaries of government employees, virtually all of whom were patronage appointees.

In the 19th century, money was spent differently too. The big events of 19th century politics - parades, speaking tours - did not require much cash expenditure. But a huge amount of sweat equity was invested in these campaigns, again very often by public employees who knew they'd lose their jobs if their party lost the election. The main uses of money in those years? The purchase of food and drink to attract crowds to events - and straight-out cash payments to bribe uncommitted voters.

Don't be too romantic about those low-dollar elections of the 19th century. There's a great story about the election of 1888 that sums up the ethos of the era:

When Boss Matt Quay of Pennsylvania heard that Harrison ascribed his narrow victory to Providence, Quay exclaimed that Harrison would never know "how close a number of men were compelled to approach... the penitentiary to make him President."