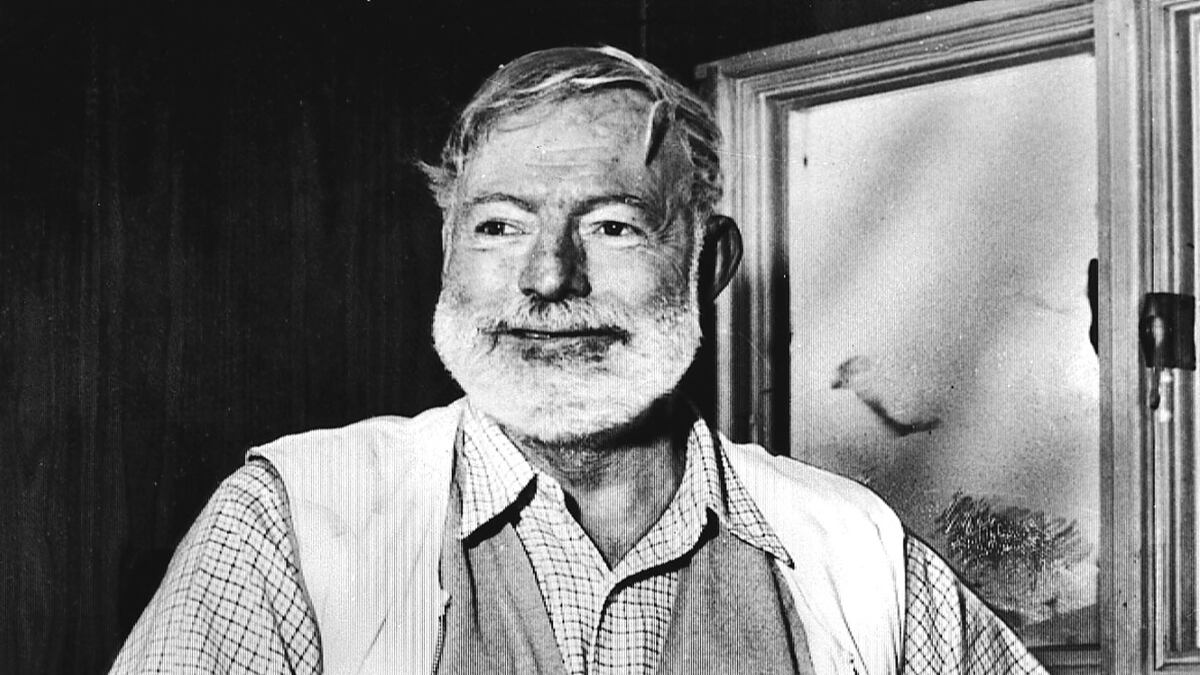

The khaki-sporting, globetrotting old man has an iconic white beard and a refined booze palate. He loves women, and women love him. He is a multilingual expert on topics ranging from big cats (“Running in place will never get you the same results as running from a lion”) to boxing to art to sharks. And he personifies a rugged-yet-sophisticated masculinity that no longer exists.

No, it’s not Ernest Hemingway; it’s the Dos Equis “Most Interesting Man in the World.” But the millennial generation loves the beer pitchman—Dos Equis sales have increased by 22 percent thanks to the ad campaign—when they should love the novelist who inspired the cheap knockoff corporate mascot, because Hemingway is the most interesting man of all time. And he never ran from a lion; he would always run to it.

Let’s just chalk up the imitation to flattery. July 2 marked the 50th anniversary of Hemingway’s death, and his legend continues to thrive. He is depicted in Woody Allen’s new film, as well as a forthcoming HBO biopic starring Clive Owen and Nicole Kidman, and a recent bestselling novel, The Paris Wife. He even had a footwear line named in his honor. (A theme restaurant with a full-scale, replicated sub-Saharan hunting range is pretty much inevitable.)

It’s a fitting time for Hemingway to could back in vogue, and not just because it’s the golden jubilee of his munching a bullet sandwich. Men no longer know how to do anything; we can use Google and Facebook and Twitter and iPhones, but if you dropped us in the middle of the woods we would be dead within an hour. We don’t know how to hunt, build shelter, start a fire, or utilize any other skills that have kept our species alive for millennia; if the electrical grid fails, the average man will have a lower chance of survival than the average Cub Scout.

We can all update our worthless status messages and post Yelp reviews, but few of us can skin a fish (without consulting an eHow tutorial), navigate by starlight (without a GPS device), or transform majestic creatures of the Southern Hemisphere into piano keyboards. If our fathers tried to pass these prehistoric skills down to us, we were too busy playing Game Boy to listen. Everything we know comes from Wikipedia, not experience.

Hemingway represented the complete opposite. Why would he sit around the house watching Netflix Instant when he could go adventuring in Spain or Cuba or France or Africa or the nearest liquor store? Why would he play Nintendo or Xbox when he could play a game called war?

But we’ve become so afraid of death that we refuse to actually live. We’re scared of the sun because it might give us cancer; we’re scared of a well-marbled steak because it might raise our cholesterol; we’re scared of bullfighting—the only real sport—so we demean ourselves with yoga and Pilates and other such unholy abominations. The closest we come to genuine thrills, genuine danger, is watching IMAX 3-D superhero movies.

Hemingway, however, knew that death isn’t the worst thing in the world. “[C]owardice is worse, treachery is worse, and simple selfishness is worse,” he said. (Also: staying married to the same woman for more than five minutes.)

Perhaps our safety-padded commercial existence is why young people are increasingly drawn to his life and works. Our entire lives are planned out for us before infancy; deviating from the standard path—SAT > college > 24/7 job—is nearly impossible. (Hemingway didn’t bother with college, instead going straight into the trenches of WWI as a medic, proof that an English degree is truly worthless.)

Independence used to mean defining your own existence; now it means paying your own credit-card bill. Freedom used to mean an open road and uncharted waters; now it means choosing between BlackBerry or Droid data plans. Living on our own terms is a foreign concept, but Hemingway bent the world to his liking through sheer gusto, which is very different than the illusion of choice on sale at the Apple Store. Why speak the truth, consequences be damned, when a single impulsive tweet can cost you a career?

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg shocked everyone by announcing that he butchers animals to fully appreciate his omnivore diet, but we should applaud him. He is such a technological icon—Facebook is the ultimate vicarious existence—yet he’s performing an intense real-world action from which most of us would recoil. We delude ourselves into believing that meat is a product wrapped in plastic at the grocery store, but Zuckerberg (like Hemingway before him) wants to know the truth, wants to feel the truth, instead of paying someone to do it for him, even though he has more money than God.

And he’s not the only millennial who seeks authenticity. We are the final generation that will remember the world before the Internet, and—despite our intuitive comfort with computers—we’ve become nostalgic for a time (and for a man) that was never quite ours. Even if the typical guy hasn’t read For Whom the Bell Tolls or A Farewell to Arms, he knows the Hemingway cartoon character, and it means something important to him. As the late English professor Matthew J. Bruccoli wrote, “Ernest Hemingway’s best-invented fictional character was Ernest Hemingway.”

But it’s more than a cartoon character; it’s something beyond our grasp, something that we feel cheated out of, something that our grandfathers all possessed. Yes, it was often more braggadocio than biography in Hemingway’s case, but our neutered, malnourished, technology-addled egos could use some braggadocio before it’s too late and the Y chromosome goes extinct, a biologically unfit victim of natural selection.

Until then, let’s stay thirsty, my friends.