Punishment arrived Monday for Penn State, in the way that punishment tends to arrives in big-time college sports: via stern words spoken by serious white men at a press conference.

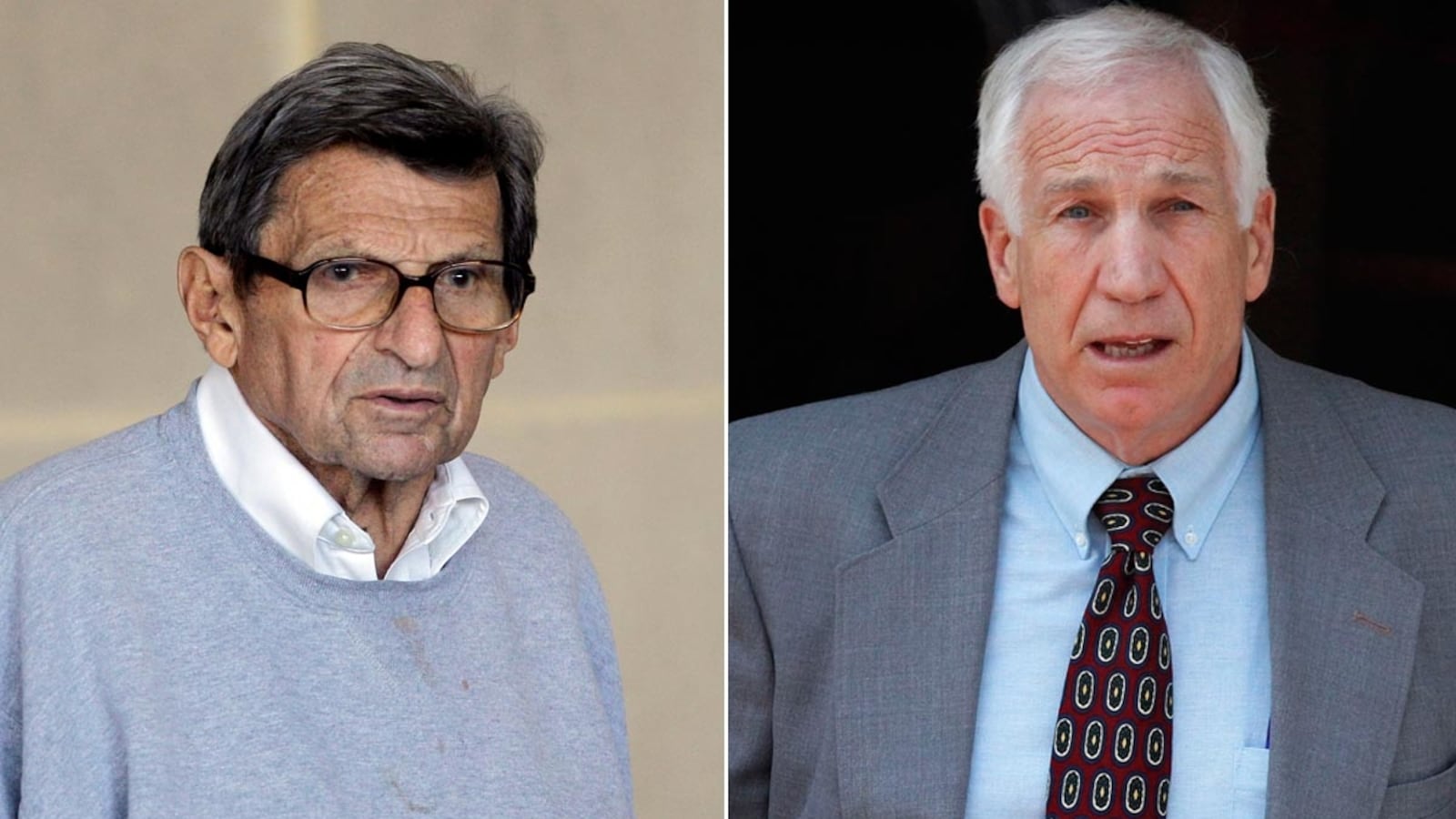

Every game that the football team won between 1998 and 2011 would be stricken from the record books, decreed NCAA Commissioner Mark Emmert. The school lost of 10 of its 25 football scholarships in each of the next four years and would be banned from playing in bowl games during each of those years; it was fined $60 million dollars, with that money going toward a fund dedicated to helping the victims of child abuse. Those vacated wins also removed the late Joe Paterno—the erstwhile saint whose awful passivity in the face of Jerry Sandusky's prolific and queasily unsecret predations was revealed in the Freeh Report—from his perch atop college football's all-time wins list.

The rumors beforehand that the punishment would be "unprecedented" and "devastating" proved accurate. But.

But Emmert and NCAA Executive Committee Chair Dr. Edward J. Ray noted in their remarks on Monday, more in officiousness than in anger, that for all its severity the penalty was not strictly punitive. It was of course hugely punitive, arguably as severe as the storied "death penalty" that Southern Methodist University received in 1987 after it was revealed that the school had continued paying its football players from a secret booster-fed slush fund even while under NCAA probation for paying its football players from a secret booster-fed slush fund.

While acknowledging that these were severe penalties for Penn State—"sanctions that reflect the magnitude of these terrible acts"—Emmert encouraged us not to think of them strictly as such. "Our goal is not to be just punitive," he said, "but to make sure the university establishes a culture and daily mindset in which football will never again be placed ahead of educating, nurturing, and protecting young people."

But Emmert's disappointed paternalism directed at a culture built around and in tribute to Paterno, Penn State's football paterfamilias, was far from the only irony.

The NCAA is often derided as toothless, but it does enthusiastically and regularly gum athletic departments that break with its metastatic rule book, an ever-expanding 434-page volume that is, if not longer than Infinite Jest, even more ornately picayune, generally opaque, and zealously footnoted. That Penn State's epic violation of the public trust and its own broader responsibilities with regards to Sandusky was not simultaneously a violation of NCAA rules is not, lord knows, a result of an insufficient number of NCAA rules.

The whole shameful affair was, instead, neither a football offense nor, strictly speaking, the NCAA's affair. No quarterback received a SUV of suspicious provenance, no unfair on-field advantage was gained, and for all the shameful evasions of Paterno and the rest, no one ever actually cheated. The offenders are in the hands of the criminal justice system and, in the case of Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett—who has been criticized for an insufficiently urgent approach to the first allegations against Sandusky while serving as Pennsylvania's attorney general—in the hands of the Keystone state's voters.

And so Emmert, unable to rely upon the NCAA's rulebook for justification, took to the bully pulpit and bullied, righteously. If the NCAA's formal job is to preserve the integrity of amateurism in college sports and its informal job is to preserve the appearance of amateurism in college sports, Emmert's punishment arrogated to himself and his organization a strange new responsibility and right—that of changing mindsets and de-perversifying cultures, however retroactively. That the NCAA has only sports-related disciplinary tools to do so apparently didn't matter.

Emmert and the NCAA seized this opportunity to encourage statewide soul-searching by means of restricting the number of scholarships Penn State can make available to defensive tackles over the next four years. “Justice has been served,” Sports Illustrated's Steward Mandel snarked, "assuming your idea of justice for rape victims is to deprive a school of its next four Outback Bowl invitations."

None of which is to say that there isn't a problem to solve at Penn State. For generations, the school happily turned its universe upside down and let proud tradition curdle into grandiosity, and then toxicity. The nauseous, slow-motion human tragedy of the past 15 years have made the school's student-section chant of "We Are Penn State" into a sad satire of itself.

But what will surely not save Penn State, or the whole disordered and misprioritized world of college football, is more of the familiar cynical-sentimental authoritarian pomp that made possible the ghoulish antivalues cataloged in the Freeh Report.

There's plenty to disdain about Emmert's decision—its hastiness and its wild high-handedness and utter lack of precedent, its reassuring misdiagnosis of a "lack of institutional control" when the actual and rather more stubborn problem is something closer to cultural regulatory capture. But the illusion of an ending—a problem solved, an institution chastened, a sport and sporting culture redeemed— that the NCAA seeks to provide may be the most offensive and least convincing part of all.