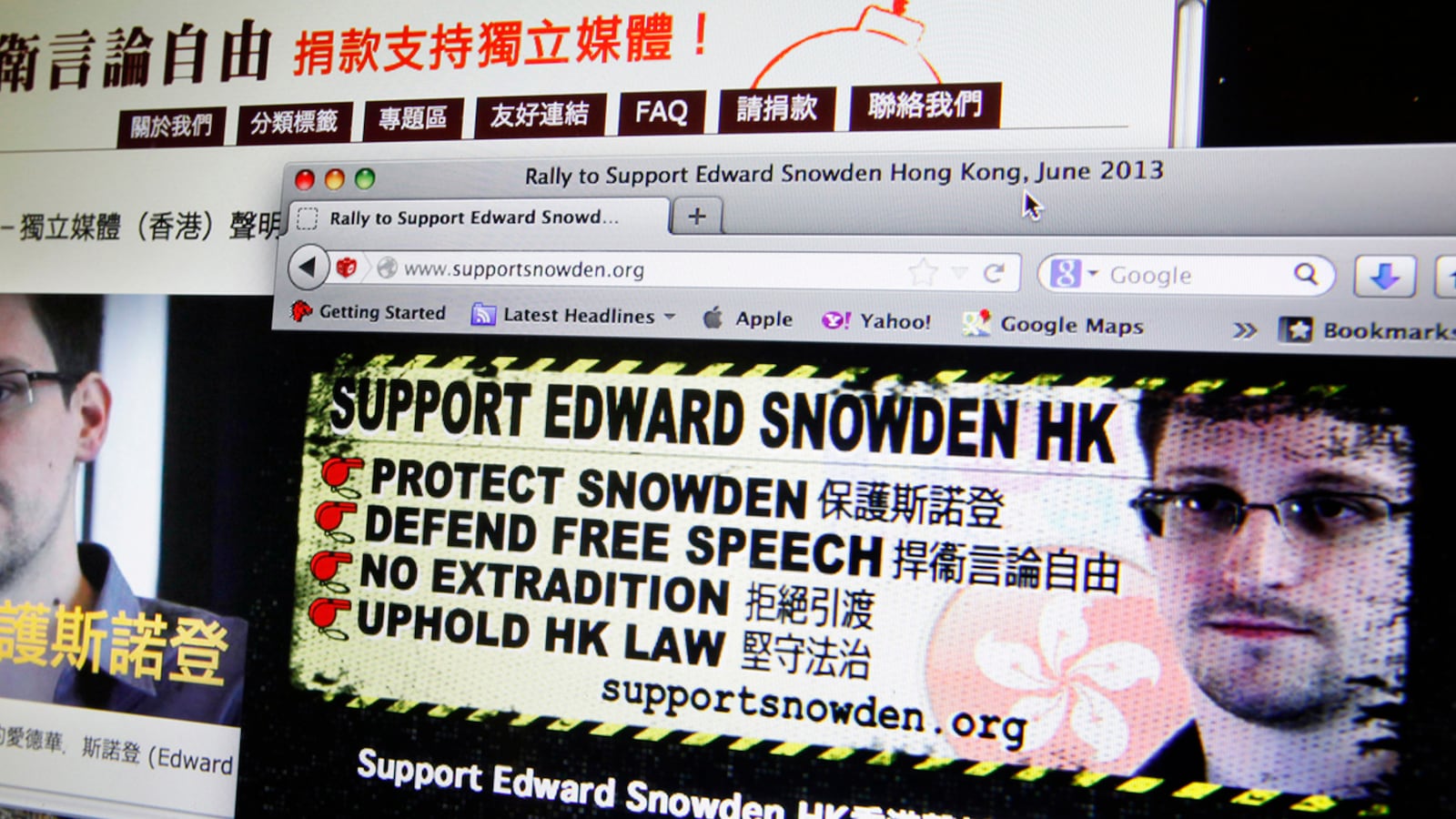

Responding to the news that the NSA whistleblower was a 29-year-old high-school dropout, senators this week questioned how Edward Snowden was granted such broad access to classified information and considered the need to overhaul the entire security-clearance system in order to prevent future leaks.

“Obviously he’s a smart guy, but what I’m concerned about is, Are we providing access to 29-year-olds more than they need to do their jobs?” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R–South Carolina) told The Daily Beast. “How expansive is this sharing of vital national-security info and should we look into restricting the pool of people with access?”

“If you don’t need to know, you shouldn’t,” Sen. John Cornyn (R–Texas) told the Beast, speaking about how an employee’s security clearance should be determined. “I don’t know what this guy actually knew, but it’s pretty astounding someone of his profile would have this access.”

The outrage wasn’t limited to the right. Senator Dick Durbin (D–Illinois) was also concerned about how Snowden was placed in his position. “This man has limited education and limited life experience with access to some of the most sensitive data to American security. Who in the world made that decision?” said Durbin to The Daily Beast. “Was that a Booz Allen decision? Was that an NSA decision? What were the standards used?”

Sen. Susan Collins (R–Maine) went as far as to say we might need a reform of the current adjudication system that determines whether an individual is fit for a secret or top-secret security clearance. She said Snowden’s level of clearance “suggests real problems with the vetting process.” “Clearly the rules are not being applied well or they need to be more strict,” Collins told the Beast.

For a person like Snowden to receive a security clearance at any level, the process would first go through the government’s Office of Personnel Management (OPM). There, background checks, interviews, and investigations are carried out. The depth of the background investigations depends on the level of clearance. Once the process is completed, the findings are sent back to the department from which the application came. In Snowden’s case, the Department of Defense would have been the final gatekeeper. There are no uniform standards for how agencies make this adjudication.

Some say there are systematic problems with the methods OPM uses to carry out its clearance investigations. “Agencies have questioned the quality of OPM’s investigations and our work has shown that the OPM investigations are incomplete,” Brenda Farrell, a director at the U.S. Government Accountability Office, told The Daily Beast. “For example, in the 2009 report we noted that 87 percent of the investigative reports for about 3,500 top-secret clearances—that were favorably adjudicated—were missing at least one type of documentation required by federal investigative standards and OPM’s internal guidance.”

Farrell said that OPM never addressed the concerns her department issued, and has yet to fix their process of collecting data. (OPM declined to comment.)

GAO found similar results in a study it conducted last September. The study looked at how government departments determined whether an open job position needed a security clearance and, if so, how they designated what level. The study ultimately found that there were no set guidelines whatsoever.

Farrell and her colleagues suggested that the Director of National Intelligence, who is in charge of overseeing the management of security clearances, issue a guideline for interagency use. Thus far, no guideline has been written.

“You don’t want someone who has no need to be handling classified information,” Farrell said. “One of the [basic] guidelines is you want to keep the number of clearances to a minimum.”

According to a source with knowledge of the process, the procedure for renewing security clearances is also flawed. A person with secret clearance gets reevaluated every 10 years and a person with top-secret clearance is reevaluated every five years. But the source says the security-clearance process is significantly swifter and less intrusive the second and third time around—making it easy for people who already hold a clearance to keep it.

The number of security-clearance holders continues to rise each year. In 2012, almost 5 million people held security clearances and, of that group, 1.4 million had top-secret clearances, according to a report from the office of the DNI issued to Congress.

Snowden was 21 when he applied for the Army’s special forces as a recruit. The source (who did not know about Snowden’s clearance in particular but spoke generally about the process) believes this role would have given him an interim security clearance. The investigation for the interim clearance could in turn have been the primary basis for him getting final security clearance when he went to work for the NSA as a security guard, says the source.

He says Snowden’s situation isn’t unique and that the system favors the young. “When you are coming in at 18, what bad credit do you have?” he explains. “When [OPM uses bad credit] as an arbitrary barrier of entry, that’s how people get clearances.”

The security-clearance system was last reformed in 2003. After 9/11, applications surged and backlogged processing for at times up to a year. In response, Congress issued a series of reforms that ultimately sped up the process.

Insiders suggest it could take up to three fiscal years and a senatorial act to overhaul the current clearance system. But some say it’s time. “Now that many efficiencies are in place and the clearance process timeline has been reduced, it is indeed time to take a closer look at the content of the investigations and standard forms to ensure questions of applicants reflect modern concerns,” argues Evan Lesser, managing director at Clearancejobs.com, a website that helps people navigate the world of security clearances and connects security-cleared job seekers to open positions.

Lesser notes that there are multiple areas that need greater scrutiny, including applicants’ beliefs on privacy issues and their financial situations. He also believes the government should consider reducing the number of years between each clearance renewal. Nevertheless, he believes these reforms are unlikely to be enacted now, given the country’s financial situation.

“Unfortunately, security-clearance reforms like the ones noted above take money,” Lesser explains. “This puts the government’s needs to review and potentially update the clearance process at odds with calls for budget cuts.”

Ben Jacobs contributed reporting to this article.