It might sound like a—heh—“big mistake” to hail a director who’s most recognized and successful work featured a hooker as its central character for his trailblazing wholesomeness. But bear with me.

Yes, Garry Marshall, who died Tuesday night at age 81, is best known for bringing 1990’s Pretty Woman to the big screen, making Julia Roberts a Hollywood supernova, and ushering in ensuing generations’ wide-eyed understanding of why prostitute Vivian doesn’t kiss on the mouth. But the juggernaut film, which made a staggering $463 million worldwide and, 25 years later, is as popular as ever, might be the greatest example of the industry titan’s greatest achievement.

From the gee-golly earnestness of Happy Days to the Princess Diaries crowning of Anne Hathaway to, yes, his iconic hooker with a heart of gold, Garry Marshall was a champion of wholesomeness, optimism, and feel-good happily ever afters for over four decades—seizing the notion that such things mattered when American culture itself might have refused to believe it…but desperately needed to.

As announced by headlines again last spring when Marshall, Roberts, co-star Richard Gere and screenwriter J.F. Lawton did press rounds in support of Pretty Woman’s 25th anniversary, it’s Marshall who was responsible for turning Pretty Woman into the prostitute rom-com fairy tale we all know and love.

The original script, written by Lawton before Disney purchased it and had it doctored by a number of other scribes (including input from Marshall), was titled $3,000.

The gritty story was so unrecognizable from the version we all know that it was described by Roberts herself as a “really dark and depressing, horrible, terrible story about two horrible people and my character was this drug addict, a bad-tempered, foulmouthed, ill-humored, poorly educated hooker who had this weeklong experience with a foulmouthed, ill-tempered, bad-humored, very wealthy, handsome but horrible man and it was just a grisly, ugly story about these two people.”

Vivian’s penchant for chewing bubblegum? In the original screenplay she’s jonesing for crack. “I don’t kiss on the mouth?” Originally: “I don’t do it in the ass, either.” Imagine that in a Disney film.

And brace yourself for that ending, a far cry from white-knight Edward riding his limo-horse to rescue maiden Vivian from her fire-escape tower. In Lawton’s version, he throws her out of his car, chucks an envelope of money at her, and drives away as she screams, “Go to hell! I hate you!”

And they all lived happily ever after?

Believe it or not, it was actually these bleaker elements that attracted Disney to the project. The studio had just made Beaches with Marshall. Both were pleased with his graduation from family-friendly sitcom guy—in addition to Happy Days, he had also created Mork & Mindy, Laverne & Shirley, and Joanie Love Chachi—to more grown-up Hollywood director.

Beaches capitalized on Marshall’s heartwarming specialty, his ability to capture the pure simplicity of familial bonds no matter the complex or untraditional circumstance—be it an alien roommate or, well, a Fonz to love—all the while confronting the darker truths of life.

Disney knew it would need something similarly dark and adult-themed to keep Marshall in its fold. The drug-addled prostitute tragedy certainly fit that bill.

Marshall, for his part, saw the script for the kernel of what it became: the story of “a girl who wanted to change her life, and did.” He was in it for the fairy tale that it ended up becoming, once it cycled through multiple other writers and producer Laura Ziskin, who famously credited herself with the film’s then-groundbreaking last line: “She saved him right back.”

It says something about the way a filmmaker sees the world that he’s able to not just recognize, but blare with Disney-wattage neon letters, the innocence and universality in a script about hooker and her john.

Critics of the film and of Marshall argue that it whitewashes prostitution and filters real-life through a lens blurred with obnoxious amounts of naiveté—something masterfully skewered in The Chappelle Show’s “Real Movies” version of Pretty Woman. But proponents of the film, the ones who turned it into perhaps the most popular romantic comedy of all time, don’t ignore the film’s corniness and aspirational implausibility. They recognize and relish it.

Without the sex, Pretty Woman could basically just be a Disney movie. That’s what makes it so great, and so necessary. It’s love in a hopeless place. It’s a rescue fantasy. It was wholesome comfort food that Americans craved at a time when greed, Wall Street, cynicism, and anxiety permeated the culture. More, it was unapologetic about being just that.

But that’s Garry Marshall’s entire body of work. Even when toeing the edge of darkness—be it themes of death or betrayal in Beaches or sex and entitlement in Pretty Woman—his projects existed in an escapist America where the ugliness and brutal reality of living at that time might exist, but are sunnily overcome.

The huge success of Happy Days makes great sense in hindsight, with the show premiering just over a year before the fall of Saigon, as the U.S. began to drastically reduce its troop support in South Vietnam.

It was based on a segment that aired during an ABC anthology series that was titled, pointedly, Love, American Style. The Cunninghams were the utopian version of the American family, living in an idealistic America. Even Henry Winkler’s Fonzie was a blissful version of “cool.” It was life as we needed to see it—how we needed to be reminded it once was, and could be again.

Versions of that same cultural yearning not only explain the initial success of the other projects he worked on, be it Mork & Mindy, Laverne & Shirley, or The Odd Couple, but why those sitcom formats—the unlikely love between the straightman and the oddball, be it the alien, the best friend, or the roommate—became the blueprints for TV comedies. Heck, there’s even a new Odd Couple today.

That wholesomeness, the safety net of love and happiness, permeated Marshall’s film work, too. Runaway Bride reassured us that Julia Roberts will always be saved by Richard Gere. The Other Sister would be cringe-worthy if it wasn’t exploding with so much heart. Heck, Marshall was so dedicated to the cause that he even thought he could tame Lindsay Lohan into being family-friendly again.

When 2001’s The Princess Diaries arrived, the state of family cinema was bleak. Something aspirational or even inspirational for women was suffering an even more devastating drought.

The Princess Diaries changed that tide, making a star out of Anne Hathaway and doing what Marshall does best: reminding us that we might be capable of more greatness than we give ourselves credit for and, retrograde as it may be, it’s always fun to get a makeover on the journey.

Perhaps over the decades we even relied on Marshall to remind us of how much we wanted or craved the escapism and the unabashed wholesomeness of the worlds he created for us. He was Richard Gere, sweeping us off our feet and away from our own realities; the Fonz whose hanging out with us made us feel cool and safe at a time when we really needed it.

Just as Marshall never stopped making movies, releasing Mother’s Day just months before his death, culture never stopped its reflexive retreat towards cynicism. His later films—the A-list orgies Valentine’s Day, New Year’s Eve, and Mother’s Day—certainly didn’t skimp on the earnestness.

They might count as Marshall’s creatively weakest works, but the snarkiness with which we treated them and their baseline messages of hope, love, and the search for happiness suggested how much we relied on Marshall when he was at his best to temper our jaded instincts.

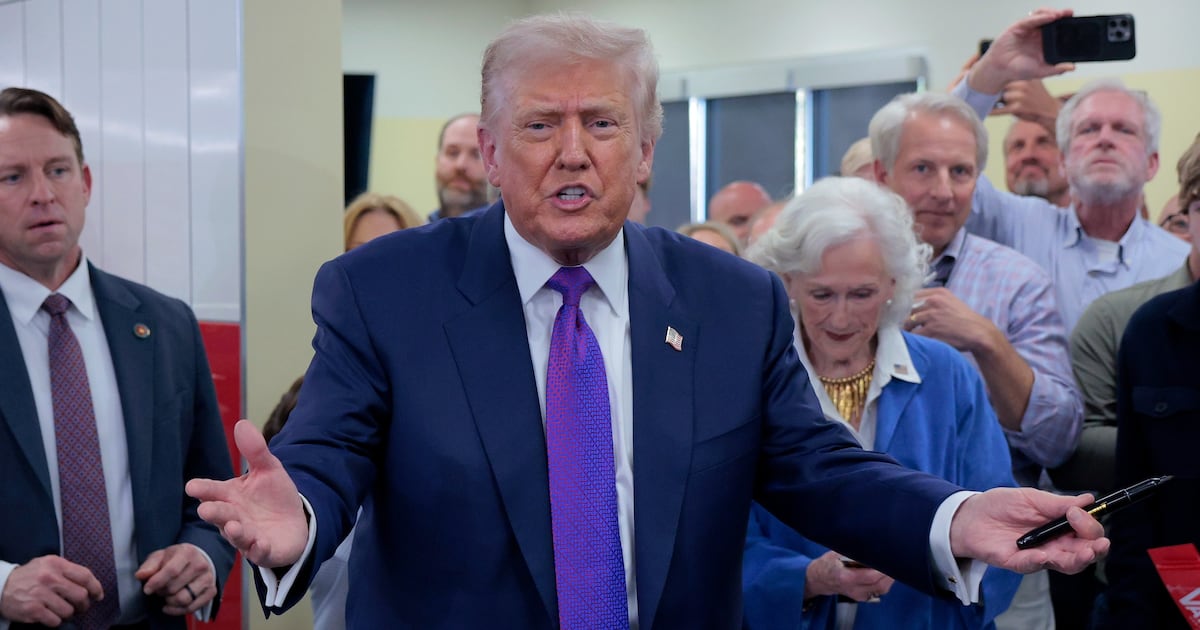

Or just watch Scott Baio, who played Chachi on Happy Days and then Joanie Love Chachi, on his mad descent to hateful tomfoolery at the Republican National Convention. It’s a stark reminder of how far we’re devolving away from the things that Marshall championed. That it’s OK to have heart.

So goodbye, Garry Marshall. In case we forgot to tell you before, we had a really good time tonight.