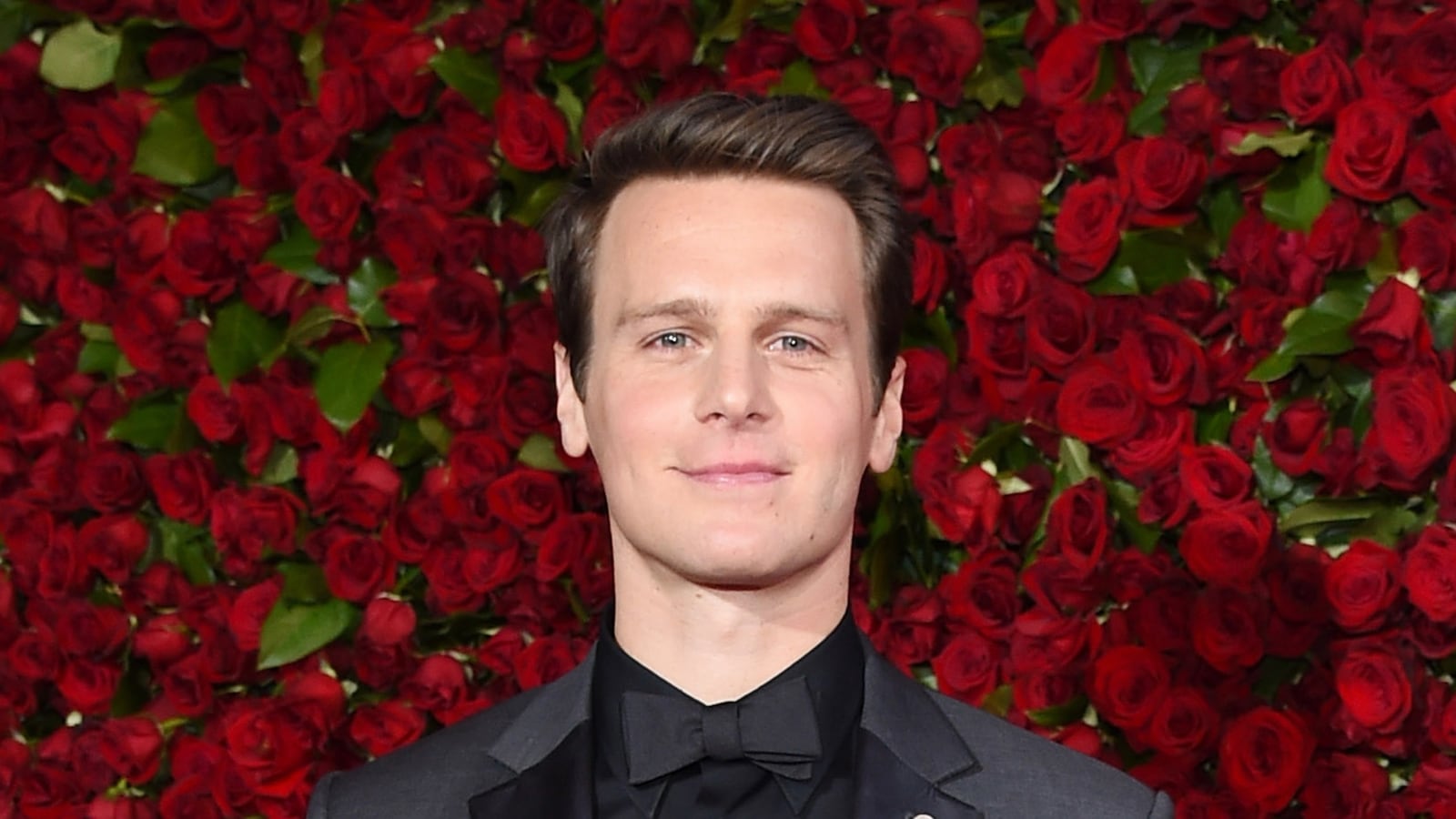

Jonathan Groff lights up when he sees my iPhone voice recorder turn on. That’s the thing about Jonathan Groff. He’s very excitable. It’s adorable. It’s charming. It’s—at least, it seems—surprisingly genuine.

He uses the voice memo app for “literally everything,” he swears, excitably (adorably, charmingly, genuinely) taking his out own phone and scrolling through a tour of recordings he’s made himself.

“Literally everything,” it turns out, is largely messages he records as his character Kristoff from the 2013 animated Disney smash Frozen—with cameos from Kristoff’s reindeer sidekick, Sven—and sends to young fans as birthday greetings and, sadly, well wishes for medical treatments.

I don’t even have to ask before he starts playing one, blushing a bit as Kristoff talks to Laila, the granddaughter of one of his father’s co-workers who was about to have surgery as part of cancer treatment. “Hi Laila, this is Kristoff from Frozen and I’m here with Sven. Say hi, Sven…” the recording begins. Encouragement from both man and reindeer to stay strong follows.

“We wanted to sing you a song, isn’t that right, Sven?” it continues before Groff realizes how long he’s been harping on this and stops it abruptly. “Anyway, you get the idea,” he says.

Should we switch gears to Looking, I ask, referring to HBO’s polarizing series about a group of gay friends in San Francisco that ends Sunday night with a farewell movie.

“Yes, to the big gay things,” Groff laughs. From Frozen to analingus on TV. “That’s my life, basically.”

He’s laughing it off as “quite the dichotomy, right?” But he’s also not kidding. The 31-year-old’s career is schizophrenic in the way that actors mostly fantasize about.

Groff recorded his lines for Frozen, for example, while shooting the first season of Looking on-location in San Francisco, doing voice takes for his Disney romantic lead on weekends while cruising for hand jobs in a park for an endearingly awkward Looking scene during the week.

“Couldn’t be more different, right?” he says, insisting that “they really informed each other,” with the riffing and collaborating he got to do in Frozen inspiring him to be looser in his performance as Looking’s Patrick, a lovably neurotic video game designer trying to find a sense of himself and his sexuality.

He shot Sunday’s film, a consolation prize for the show and its fans after HBO canceled the series following two low-rated, but much-debated seasons, while on hiatus from diva-walking away with his few short scenes in his Tony-nominated role as King George III in the cultural juggernaut Hamilton.

Even now, promoting the TV movie in a Manhattan hotel suite, he’s guzzling coffee, exhausted after performing a one-night-only musical event at New York City Center opposite Tony-winner Sutton Foster, whom he first met as a teenager after standing in the freezing cold at the stage door after a performance of Thoroughly Modern Millie. Risking tonal whiplash, they rehearsed on weekends when he wasn’t in Pittsburgh shooting his next role, on David Fincher’s new Netflix series Mindhunter, about the FBI’s elite serial crime unit.

“It all plays on each other,” he says, referencing his various theater and screen projects. But Looking is different. Looking is special. Looking is personal. “The show has changed me for good,” he says.

When the first season of Looking premiered in 2014, it arrived pre-packaged by critics and TV writers with zeitgeist-ready branding. It was “Girls for Gays.” Sometimes it was “Gay Sex and the City.” Either way it arrived with huge expectations—chiefly to speak for an entire community of people who rarely get to see themselves on TV—but met few of them.

More, for many gays it was the worst possible thing: boring.

It’s hard not to absorb one of the best lines from Sunday’s film through the prism of those early responses. “I love when gays argue with other gays about being gay,” Lauren Weedman’s Doris chirps. Looking wasn’t everything for everyone. It was a hyper-specific, almost diarist look at a group of gay men in San Francisco dealing with their friendships, love lives, and sex lives. Looking was just Looking.

So when season two finished airing a year later and HBO made the decision to cancel the series, tying things up with a TV movie, the reaction was completely different. “It was an outpouring of love!” Groff says, almost still in shock himself.

But it was more than that. It was a sadness, a eulogizing of a show that, finally, brought to TV some of the nuanced, organic, everyday conversations and concerns of the gay community. Now it would be gone.

For his part, Groff found himself suddenly a de facto mouthpiece for those conversations and issues, discussing everything from HIV panic, PrEP, and topping vs. bottoming to his own experience coming out and dating. It’s a role he rose to admirably even if, as he explains to me, it took him a while to be comfortable doing so.

“Being gay and in every scene having to explore gay identity, you can’t help but think of your own gay identity and of where you fit in the community and who you are and the issues we talk about it,” he says.

There’s one scene from the Looking film in particular that struck him. It’s that aforementioned analingus scene—which, get your DVRs ready, makes that groundbreaking How to Get Away With Murder one look rated G. Rather, it’s what happens after that scene, when Patrick discovers that his one-night stand, who is 22, has been out and having serious relationships since he was 16 years old.

Patrick’s reaction mimics that of many gay men who didn’t feel comfortable, for myriad reasons, coming out until later in life: awe, admiration…and a lot of jealousy. It turns out that reaction also mimics Groff’s in real life.

“I love that scene because I have that with young people I meet now, even at the stage door,” he says. “Even like visiting my high school there were kids who were out. I was like ‘What!?’ I couldn’t even wrap my mind around it. That someone would go to prom with a guy is crazy to me. It’s amazing to me but I couldn’t even believe that was a possibility.”

Groff grew up outside Lancaster, Pennsylvania. His father was Mennonite. His mother was Methodist. His upbringing was happy and suitably adorable.

When he was 3, for example, he dressed as Mary Poppins for Halloween. “I had a carpet bag and everything,” he says. His family raised goats on its farm. Later, after co-starring with her in Spring Awakening and then on Glee, he named one after Lea Michele. A few years ago, Lea Michele gave birth to twins.

He knew he was gay, but he didn’t know he could say it. He remembers driving by a billboard of Will and Grace when he was in middle school, and even though he watched the show he didn’t feel like he was a Jack or a Will. But just the fact they existed made him feel less alone.

Groff remained in the closet all through his run in Spring Awakening, from when he was 19 to when he was 23. He had a boyfriend whom he lived with that entire time. Laughing as he admits it, Groff called him his “roommate.” He even thanked him in his Playbill biography.

“In Spring Awakening, I played this rebellious character who was very unlike who I was in real life,” he says. “He didn’t let the world define him and spoke his mind and was a passionate rebel.”

It was in stark contrast to his own life: “I was closeted, living with this guy. I’m such a people pleaser, in every sense. The idea that if I came out and was gay and it made people feel uncomfortable, I would never want that.”

When he left Spring Awakening, he says, he realized “I had cultivated this side of myself and now I had nothing to do with it but put it into my real life.” He came out. He broke up with his boyfriend. He started to evolve.

When Groff came out to his parents he gave them the same line that so many gay men tell their parents in order to reassure them that, sure, they’re gay…but they’re not that gay.

“I said, ‘I’m gay, but I’m not going to be in a parade or anything,’” Groff remembers, shaking his head as he laughs at the memory. Cut to 2014, when he was asked to be the Grand Marshall of New York Gay Pride Parade. Cautiously, he said yes. He was still uncomfortable.

“For me, at least, it wasn’t like I came out and then was like and now I’m fine!” he says. “It’s more complicated than that. I came out and it was a slow evolution.”

“Doing the gay pride parade, I really realized that I was proud to be gay. It’s one thing to be out and it’s another to be proud of it. I think when I first came out it was like OK I’m gay, but if I could not be gay I’d not be gay, but I’m gay. That’s how it was when I first came out. But Looking really was an experience that changed all of that for me.”

He had already been publicly out for years by the time Looking came along, and was steadily and successfully working in Hollywood. He became a household name on Glee. An indie darling in Ang Lee’s Taking Woodstock. A sex object, thanks to a nude scene in C.O.G. He and actor Gavin Creel were, at one point, Broadway’s cutest couple. (They broke up in 2010.) Then he and actor Zachary Quinto were TV’s cutest couple. (They broke up in 2013.)

But Looking required something different from him. It required that he be, well, gay.

“It was really publicly owning my sexuality,” he says. “It was a different step. I mean, now I’m fucking guys on TV.”

Some gay men like to joke that one of the reasons coming out is hard for parents and parental figures to take is because it forces them to picture you having sex with dudes, and that makes them uncomfortable. Groff sort of upped the ante on that. He was literally, as he just said, “fucking guys on TV.”

And that’s precisely why his parents didn’t watch Looking, he says, recalling one particular horror story. In the middle of season two, he told his parents that he’d put together a few sex-free clips from Looking to show them. Perhaps thinking he was being proactive, Groff’s father beat him to the punch, flipping on a season two episode one night that happened to be on HBO.

“And of course…” Groff begins. You know where it’s going.

“In season two I have like one sex scene with Russell Tovey. It was the one where I fuck him, the top to bottom episode.” His father called and relayed the horror. “He was like, ‘I turned to the channel and I saw this British guy and you were both naked and I saw him go for a condom.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t watch it.’”

In a way, though, the reaction exemplifies the exact service that Looking provided.

Groff and I joke about the ass-eating scene that you will certainly be talking about come Sunday night. “I love doing those scenes!” he insists, possibly the first actor to perform that and not deliver the rote “it’s always awkward and robotic…” line, as instructed in the Actor’s Bible. But the scene, in all its graphicness—stark realness, actually—means much more than that.

“These sex scenes are an opportunity to illuminate something in a character but also in life for people,” he says. “Like this is what actually goes down.”

He likes to tell the story about how many of his straight friends didn’t realize that gay men can have sex facing each other until they watched his character do it in a scene in Looking.

“I think [Looking creator] Andrew Haigh does a really good job capturing the reality of sex instead of just the salaciousness of sex,” he says. “So the sex scenes can be sexy but they also feel like real sex. It’s not like you’re watching perfectly shined, groomed bodies banging in soft lighting. You’re seeing what’s real. It’s a little awkward. Kind of hot. You know?”

I do. It’s kind of like Jonathan Groff, really.