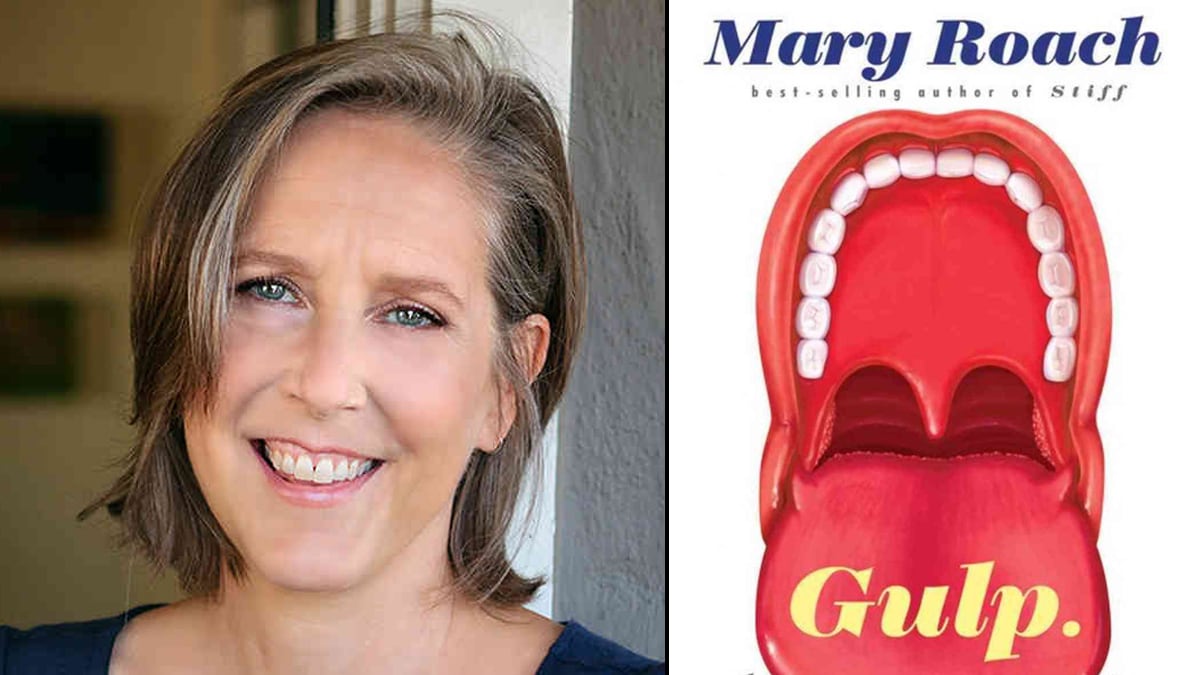

In her last book, Packing for Mars, science writer Mary Roach set out to describe the extraordinary engineering feats that keep human bodies functioning in deep space. In her latest, Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal, Roach—whose previous bestsellers have also examined cadavers and the mechanics of coupling—focuses squarely on the earthiest of arenas, tackling the “last taboo” of the body by charting the squishy work of art that is your guts.

As droll and unflappable as ever, Roach makes the rounds from tasting rooms to fecal transplants, approaching gastroenterology via her mix of anthropology, psychology, history, and scatology. It is through President James Garfield’s unfortunate experiences with rectal feeding, for instance, that readers are introduced to the absorptive properties of the colon. Elsewhere, she details just what Jonah would have been up against inside that whale and learns about the physics behind how we eat with our ears.

In the end, it turns out that in significant ways, our humanity turns on our ability dispatch with a handful of Doritos. “You are what you eat,” Roach writes, “but more than that, you are how you eat.” Think on your cousin the gorilla, less digestively efficient, who will never get around to penning the great American novel partly because it’s busy just trying to process around 40 pounds of vegetation a day.

In the edited conversation below, Roach discusses Elvis Presley’s megacolon, eating raw eyeballs, and trying to stay off the Dalai Lama’s shit list.

In Gulp, you write, “People who know anatomy are often cowed by the feats of the lowly anus.” The book as a whole ends on a note of awe and respect reminiscent of your feelings for space travel at the close of Packing for Mars.

Yeah, very much so. I think this is a losing battle, but I would love people to come around a little bit from the general position of disgust and revulsion they have for their insides, especially the below-the-waist portion of their insides. Every step of the way, I was kind of floored by how effortlessly complex and amazing it all is, and I would like to impart a little bit of that to people. You go through life with these things inside you—these guts, these organs—and you never see them and consequently you never think about them. Until something goes wrong, and then you think about them all the time.

One of the themes running through the book is how that disgust can cause our minds to get our bodies backwards. This has led to some kooky theories and practices, as with Sir Arbuthnot Lane, the Scottish surgeon who went around cutting out people’s colons as a cure for constipation.

Exactly. Our understanding of our bodies is very simplistic and intuitive. It’s not like everybody can take an advanced biology/physiology class—there’s no reason why people should know this stuff—but [then] we’re very susceptible to somebody coming along and saying the colon is a revolting, disgusting thing, and you’d be better off without it. It’s like, wait a minute, who says it’s revolting and disgusting? In what way? It’s life saving. It’s vital to how we thrive, and who we are. The arrogance of thinking of going in and cutting it out just because it’s stinky—it’s pretty astounding.

Speaking of disgusting, among the things you’ve done in the service of your books, how would you rank eating raw narwhal skin?

Oh god, it was so good. I do have a certain amount of moral discomfort because of the situation with whaling. I don’t know exact figures on narwhal, and I know the Inuit population is allowed to hunt some. But, nevertheless, we as Americans feel very uncomfortable eating large sea mammals … But in terms of it as a food item, I loved it. I thought it was really, really good. It wasn’t a problem at all.

The arctic char eyeball, on the other hand, which I had the day after—a raw eyeball is a whole other matter. That was something I ate because I was in the company of the elders of the town who said to me, “This is the best part, and we’re giving it to you.” They were probably lying. They were probably like, “Eh, let’s give her the eyeball!” But narwhal, not a problem.

You have a line in the book, “to a far greater extent than most of us realize, culture writes the menu. And culture doesn’t take kindly to substitutions.” It’s fascinating, how intractable eating habits can be, as with the case you cite of British explorers actually starving rather than eating like the “natives.”

That was unbelievable—the sense that food is representative of class, and that by eating something that’s lower class, you’re debasing yourself as a human. And the fact that even in the face of starvation, someone would refuse to eat raw seal liver, or whatever it was that the locals were saying, “Hey, this is probably something you ought to have. You look pretty hungry, and it’s pretty good.” That’s astounding to me, that class[ism] and racism, extend all the way to the point of starvation.

One thing you’re really good at is locating the larger stories in your anecdotes. Take your chapter on transplants of biological secretions, where you write that, among other things, they have been very successful in treating life-threating conditions such as certain colon infections, which kill more people in a year than AIDS or antibiotic-resistant Staph. Your approach turns it into a commentary on our health care system.

The fecal transplant has been quietly going on for a while … It’s so complex, and to do it justice in one chapter is just impossible. So I chose to look at the reasons why it has been so slow to catch on, given that the first one was done in, I think, 1958, by Ben Eiseman. Why hasn’t this become something that anybody who has a C. diff infection can just go into any facility, and say, “I need a” whatever euphemism they want to use for it? Is it the ick factor, is that actually what’s holding it up? It turns up it’s not entirely that. It’s also the way new procedures are introduced, and there’s no money to be made from shit. There’s no funding body to push through the approval process or even to push to figure out how it’s going to be coded in the billing. That was fascinating to me—that whole process by which something gets accepted as a legitimate medical procedure. So something like a shit transplant, that’s got to be a little awkward, for a lot of reasons.

At one point, you discuss how scientists are just beginning to understand the critical role our gut flora plays, including determining whether we can absorb certain nutrients, or even maybe influencing what we choose to eat in the first place. Which leads to some interesting philosophical questions about the self.

I wasn’t expecting to come across anything remotely philosophical, but there were points where it did cast an interesting light on the notion of the biological self.

Talking to Alex Khoruts, the doctor who does fecal transplants, we’re talking about the unbelievable ratio, that there’s nine cells of micros to one cell of you. And he mentioned at one point that it is a philosophical question, who owns who? And who is controlling who? It’s a very, very new science. People are fascinated by the microbiome, this enormous, incredibly complex universe inside you, that until very recently really was just sort of ignored or just viewed as interlopers, like ugly roomers. All of a sudden we’re confronted with this notion that, it’s like a Ray Bradbury story—they might be running us. I also loved the Paul Rozin paper where he talked about disgust and all these bodily substances, as long as they stay in the confines of the self we have no problem with saliva, blood, semen, shit—as long as it’s in there, it’s part of us. But, even if it’s your own, as soon as it leaves the confines of the body … you can map that: something’s on your tongue. Stick out your tongue, does it disgust you? No, the stuff on the tongue doesn’t disgust you. So the boundaries of the self are extended out of the mouth for the distance of the tongue.

In all of your books you display a generous nature toward your subjects, but Gulp, while often funny, has some particularly compassionate moments. This was true in sections such as when you tackled the circumstances around the death of Elvis Presley, who might have suffered from a sort of paralysis of the colon.

By and large I have a lot of fondness for the people in my books. I never knew Elvis Presley, but just hearing his story, and realizing what he’d gone through, just in terms of his colon alone, I really felt for the guy. I felt bad for him. He’s beyond a human being. Elvis is Elvis; he’s an icon, a concept. But when you start to read the autopsy report—or I didn’t have the actual autopsy report—but read the description of what his colon looked like, and what that must have been like for him, he became a person rather than a black-light poster. He became real in a way he’d never been before.

That description of the blockage being as hard as stone, and the circumference of his colon, suddenly, he’s this man with a really god-awful medical problem. I didn’t want to make light of him or that. I think I felt a certain amount of discomfort even shining a light on that, because I knew in life that had been something that was very embarrassing to him. I think that’s part of why you had that reaction to that chapter. I felt I had to tread carefully because the man, were he alive, would not appreciate a discussion of his bowels. Although I think it exonerated the doctor and him in terms of the drug situation a little bit.

The popular perception of his death is more damaging to his reputation.

Yeah, very much so. People hear drugs and they just think, Oh, he’s a substance abuser. The drugs that he was taking by and large were prescription, and you can definitely kill yourself with prescription drugs, and he was. He was very much in that damaging routine that celebrities on the road get into. It’s not that the drugs didn’t take their toll. It’s just that there was this other horrific thing he was battling. And you really had to feel for the guy.

Were there any good bits you had to leave out of the book?

There was a chapter I thought about including that was related to religion. There is a pill in Tibetan Buddhism that contains a lot of esoteric ingredients, some of which are bodily substances. But it is so much off in its own realm, and to take it out of the context of Buddhism I think does a disservice and makes you go “ew, this is disgusting. These people are eating” fill in the blank. On the one hand, it would have been fun to go to Tibet and try to research it. It’s very secretive, and I wouldn’t have gotten far. But I just didn’t think it was fair to Buddhists to focus on one particular element of that pill, because the religious texts regarding it are so incomprehensible to me. As much as I found it fascinating, I didn’t want to cheapen what is obviously a sacred undertaking for Tibetan Buddhists. And I don’t want to be on the Dalai Lama’s shit list.