What goes through the mind of a school shooter? In the past days, we've all asked that question. The following is one attempt at answer. It was sent to me by a young person living in an East Coast metropolitan area. I am satisfied that the autobiographical facts described are true to the teller's memory and experience. The story is troubling, but important to consider. For reader ease, I have broken the essay into three parts. I am glad to report that the author is now personally stable, a college graduate, and gainfully employed.

This is the first in a three part essay that was submitted by an anonymous young writer.

******

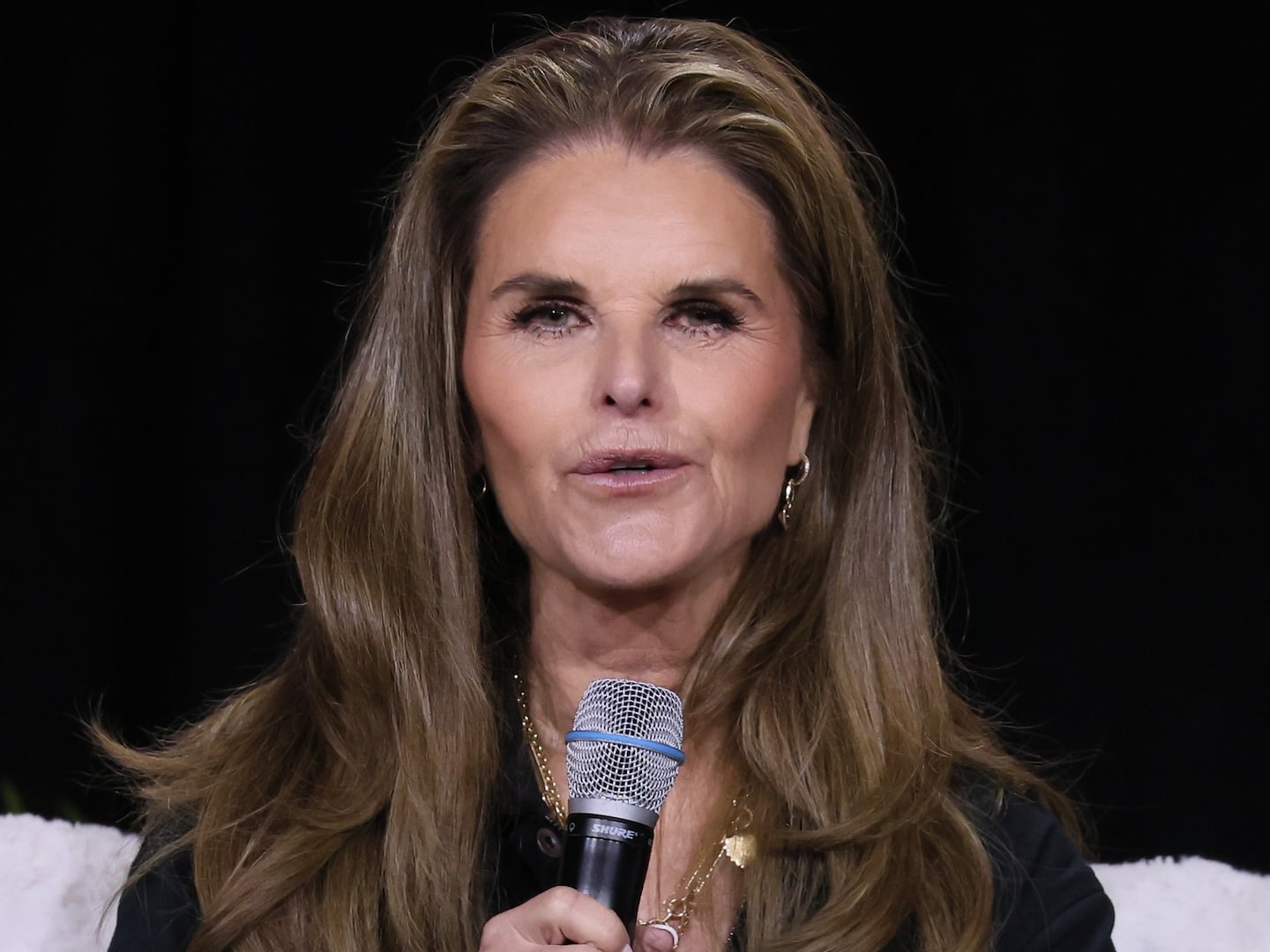

Recently, the Huffington Post published an article titled "I am Adam Lanza's mother" by a woman named Liza Long. The article presents a picture of a 13-year-old boy who threatened his mother, sometimes going so far as to pull a knife on her, scream obscenities at her, and leap out of cars as they're driving down the highway.

The rest of the world has reacted to the idea of such a child with horror and incomprehension. I sympathize with the horror. I can only wish that I shared the incomprehension. I understand, intimately, how Liza Long’s son feels. I was like him.

Like the author of that piece, Liza Long, my mother had no idea what to do about my sudden transformation (in my case, around 16) into a borderline homicidal maniac. Like her son, I used knives to try and make my threats of violence seem more real. Like her son, I would leap out of our car in the middle of the road just to get away from my mother, over the most trivial of offenses. Like her son, I screamed obscenities at my mother shortly after moments of relative peace. And worse than this poor woman's son, whose mindset toward his peers we can only guess, I will admit that I fantasized multiple times about taking ordnance to my classmates.

By the logic which leads Liza Long to say, "I am Adam Lanza's mother,” I have to say: “I was Adam Lanza.”

I don't say this to get attention. It's in the past, and I honestly would prefer to pretend those years of my life never happened. I’ve struggled hard for psychological healing, and I sincerely believe I’ve made progress.

However, given recent events, I have a warning to offer - and an obligation to offer it.

I hope that by giving this explanation, including why I was the way I was, the world will work out that it is possible for kids like me – kids contemplating the most awful crimes - to get better. Kids like me and Liza Long’s son are not psychotic lost causes. We can be stopped. We can be saved.

What was wrong with me exactly is a complicated subject – I’ll leave that for the next installment of this story. For now, I just want to explain what goes through the head of a potentially dangerous teenager. If you are the parent of a child like me, or know someone who is, please listen:

We don't take our rage out on you because we hate you, or because you're bad parents, or even because we're evil. We take it out on you because we know you're a captive audience. Often, you're the only audience we have.

When I attacked my mother or got angry at her, it had very little to do with her and much more do with the feelings of rejection and helplessness and crazy that had been percolating in my head from the experience of isolation that comes with being different. And isolation makes us even more different than we started.

I'm not saying that angry, abusive, and dangerous teenagers just need to be hugged. There may well be cases where mental illness has set in and become so drastic that hugs alone would be comically insufficient. But what I am saying is that for me, at least, feeling loved and wanted by somebody was a precondition to health. If I had ever come to feel that my mother didn't care about me, then everything would have looked hopeless. I would have given up on healing and started coming up with other, more drastic measures to make the world stop hurting me. Because of the way the media covers these events, it wouldn't have taken a genius to figure out that for a social outcast of my stripe, there really was only one way to make the world stand up and take notice. My mother was the last line of defense that stopped it from getting that far.

Maybe a parent of a difficult child will read this and think, “I have made every possible effort to show my love and support – and my kid is still a little monster.”

The problem is that what is obvious to a normal adult is not always obvious to an abnormal child. Children like me will look for reasons to ignore love, especially if we feel the people who love us are also hurting us.

That seems to be what happened between Nancy and Adam Lanza. Nancy Lanza had spent time volunteering at Sandy Hook elementary. She also, understandably, had sought to have Adam involuntarily committed. Those two facts together seem to have led Adam to the conclusion – perfectly logically from the point of view of a kid like him and like me as I then was – that his mother cared more about the children of Sandy Hook than she did about him. In his reaction and rage, a shooter was born.

Parents, I cannot stress this enough: the healing process starts with you. Not the mental health community. Not the police. Not the government. Not the school. You.

I know it’s hard. I know that we’re asking for the most love when we are least loveable. I can only promise that we – or some of us – will sooner or later understand and recognize the heroism of what you did.

If you throw your child away like a broken toy, or treat them like someone else's problem, they will be lost altogether. Your child may be too far gone for you to fix alone, but that doesn't mean you can do nothing. My mother did almost everything, and if you ask her now, she'll admit she was deadly worried about me ending up on the news - as worried about me as Liza Long is about her son.

She was right to be, because at one time in my life, I was Adam Lanza. I was Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. I was Seung-hui Cho. I was James Holmes. I was Michael. But my mother held fast. She is the main reason why, unlike theirs, my experience can be described in the past tense.

Part Two is now online, and can be read here.

Part Three can be read here.