Years ago, when I was a restaurant line cook who sometimes took college classes, I visited a friend at her mother’s house in Virginia. Her mom was an enthusiastic cook and a gracious host. She happily showed me around her kitchen, and we talked about food. There was a pressure cooker on the stove, and I asked what was in it. Green beans, she answered.

I was about 20 and good cooking was, to my mind, a Francophilic thing, done à la minute, grill and garnish, all things al dente. I’ll blame my fascination with Julia Child’s television show.

My friend’s mother liked French green beans very much, she said, but she also liked Southern green beans. She grew both, and she cooked the Southern ones in a pressure cooker with ham.

My mind was blown.

In the arrogance of my youth, I’d simply thought that people who liked green beans that way didn’t know any better. I thought people ate that way not because they liked to cook that way, but because they didn’t know how to cook.

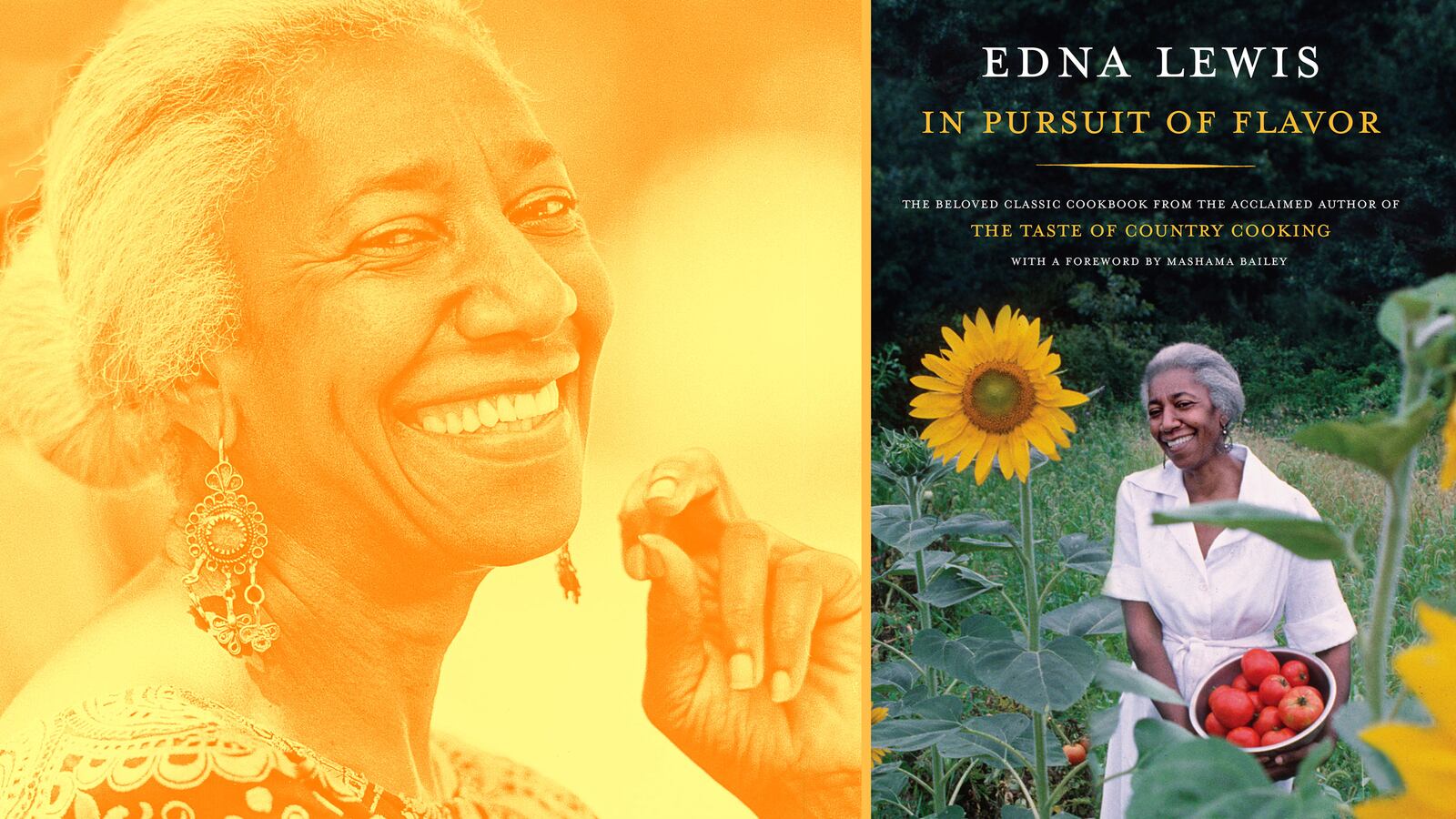

I have seen no better representation of open-mindedness and the all-embracing impulse than in Edna Lewis’s cookbook In Pursuit of Flavor, which was recently reissued by Knopf. Originally published in 1988, the book is composed of six chapters, each focused on the source of the food. Instead of “meat,” the section is “From the Farmyard,” and therefore includes eggs. The recipe for Brunswick Stew (which calls for squirrel, but allows that you might simply use more chicken in its place), is right next to the recipe for Roast Pheasant with Currant or Gooseberry Sauce.

Lewis, who passed away in 2006 at the age of 89, is renowned (sainted, even, and deservedly so) as the cornerstone of African-American cooking and Southern foodways. For her role in that there are no plaudits too great. She is the sine qua non.

She wrote in In Pursuit of Flavor: “I grew up in Freetown, a small farming community in Orange County, Virginia, which was founded by my grandfather and his friends shortly after his emancipation from slavery.”

Like the cookbook that preceded this one, The Taste of Country Cooking, published in 1976, In Pursuit of Flavor leans heavily on her upbringing. The flavors of her mother’s kitchen are the flavors she chased for the rest of her life.

“I feel fortunate to have been raised at a time when the vegetables from the garden, the fruit from the orchard, and the meat from the smokehouse were all good and pure, unadulterated by chemicals and long-life packaging.”

What’s interesting about Lewis is that she spent most of her life living in New York. What is striking, in the context of our current food scene, is how wide-ranging and inclusive Lewis was. She wasn’t exclusively Southern at all.

For while there’s nothing more Virginian than Brunswick Stew, the recipe for roasted pheasant, right next to it, seems almost British. She doesn’t call her Leek and Potato Soup vichyssoise, but it is, and whether you think it came from America or France, it is in no way a Southern dish. Except that, of course, there isn’t any reason it shouldn’t be. If you grow leeks and potatoes, and there’s a dairy cow around, it’s really only a matter of time until those things come together in the soup pot.

What this cookbook is, then, is worldly. There are recipes for preserves, cucumber pickles, and canned peaches, as one would expect in a cookbook from a cornerstone Southerner. There are also recipes for Christmas Stollen, Ethiopian Bread, and Red Snapper with Olive Mayonnaise. Useful, achievable recipes abound—she isn’t showing off and she would never veer off into the realm of caricature. There are no recipes for mountaintop lowcountry heritage benne seed boil with country ham and pimento cheese stuffed soft-shell crabs.

There is a recipe for soft shell crabs, however, that is nothing but that—everything you need to know about dredging and pan frying “just about the most delicious shellfish you can cook.”

Right next to it is a perfect encapsulation of how limitless, and how wonderfully cohesive, Lewis’s way of thinking about food was. Herring Fillet in Cream Sauce with Garlic, Tarragon, and White Wine, begins with a rejoinder not to worry about the bones. She then recalls her eagerness to catch herring during its short Spring season, since there were no fish shops in Freetown. She poaches the fillets in what sounds like a very French concoction to me, serves them with mushrooms and scallions, and garnishes with a Bombay mango. The recipe is like an intersection of influence—childhood, seasonal availability, French cookery, and the nice mangoes she found at the Union Square Green Market.

Because she is not afraid of this confluence—the pieces that make up Lewis—the book comes off as a serene testament to how people actually cook and how her recipes are a true reflection of her experiences.

It makes me want to eat with her, at her house. Instead, I’ll make her roast chicken and biscuits.