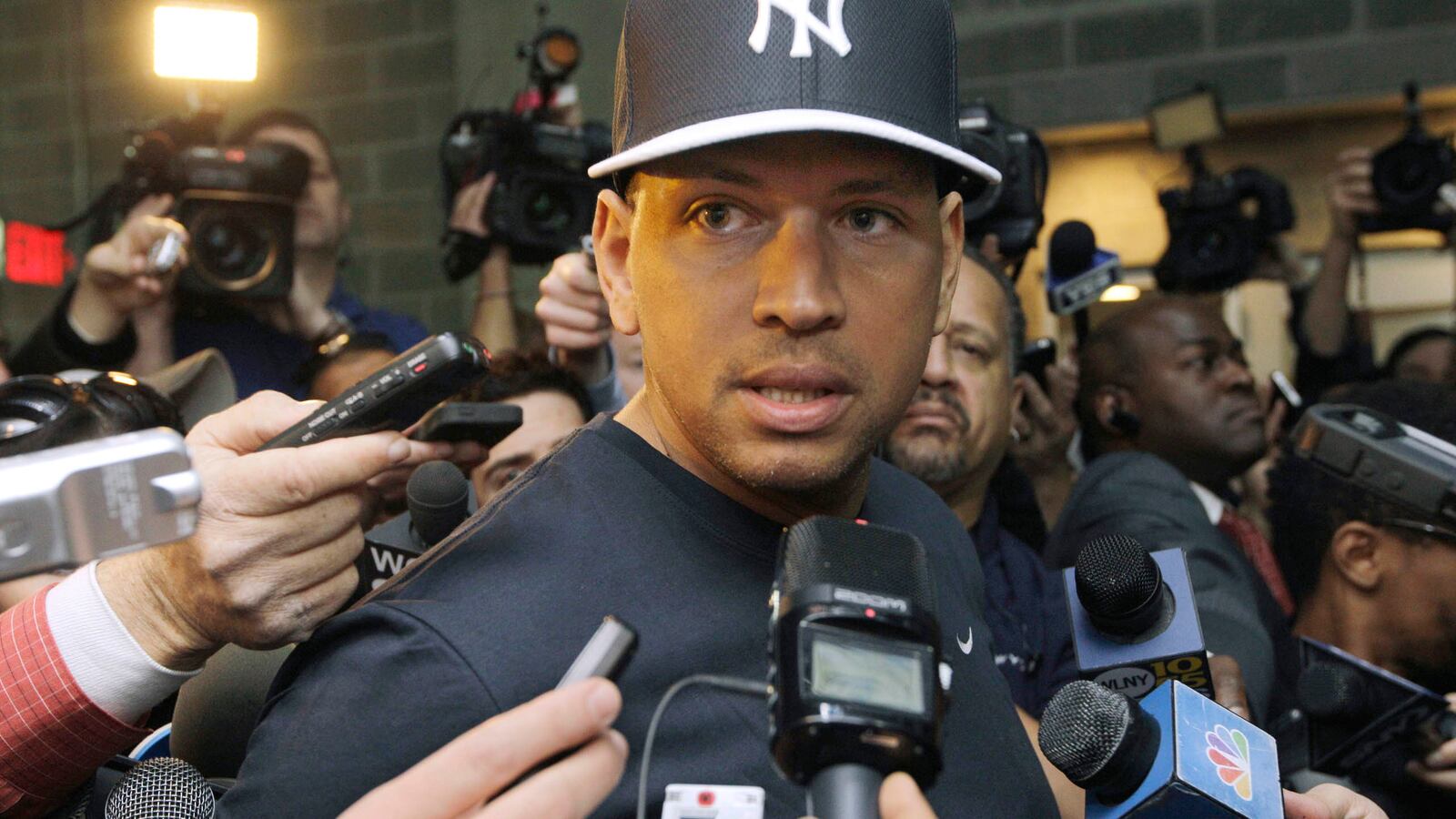

You can get them in any bodega in New York City and in less upstanding newsstands, delis, and convenience stores elsewhere. They’re little packets full of powder, maybe Rhinoceros Horn or maybe Rhinoceros Penis or (more likely) funky cornstarch, along with a bunch of other exotic extracts that may or may not exist, or anyway exist in the packet stashed for sale between the condoms and menthols. There is no guarantee on them and no real reason to believe that these bodega packets—which will give the person who ingests the contents a burst of energy or granitic erections or both—do what they say they’ll do. But some people must be desperate enough to believe in and buy them, because there they are, leering lewdly from behind the scratch-and-win tickets. These packets are not necessarily the same thing as human growth hormone. That’s the banned substance that 20 baseball players—including all-stars such as Alex Rodriguez, Nelson Cruz, Gio Gonzalez, Melky Cabrera, and Ryan Braun—allegedly received from a sketchy Miami pharmacist named Tony Bosch, an offense for which Major League Baseball is preparing to hand out 100-game suspensions, according to a bombshell report by ESPN’s T.J. Quinn. But HGH, it’s worth noting, is not so unlike those sketchy packages of bodega boner powder.

HGH is indeed banned under the Joint Drug Agreement between MLB and the Players Association. There is also no reliable test for HGH anywhere on the planet. Nor is there any indication that HGH does much of anything for player performance beyond, as Tim Marchman pointed out on Twitter, helping to burn fat when used in conjunction with more proven and equally banned performance enhancers such as steroids. “It no doubt makes players who use it look like porn stars,” Marchman noted, but whether HGH use makes for better ballplayers is in serious doubt. That is beside the point to a certain extent—HGH is against MLB rules, and rules are rules. But the vigor with which MLB has pursued this case calls into question just what the point of all this truly is.

***

Baseball is an exceedingly difficult game. Mets fans receive painful reminders of that nightly, but every fan and player knows it. What made baseball’s steroid era perverse was not that all those drugs somehow made the game easier—there are not enough steroids on earth to turn your author into F.P. Santangelo, let alone Barry Bonds—but how the pervasiveness of PEDs threw the sport out of balance.

The game looked and felt different, and not just because a few players on every team looked like extras from Pain & Gain. Hitters and pitchers alike changed their approaches, and the game got a little dumber, puffier, and more like professional wrestling. That both Bonds—a sure-thing Hall of Famer before he began his steroid use and started rewriting the record books—and an end-of-the-bench goofball like Santangelo felt compelled to resort to performance-enhancing drugs shows just how juiced the game was a decade and a half ago. But it’s also a reminder that the game is difficult for everyone who plays it at the highest level. The lack of evidence for HGH as an effective performance enhancer is just as immaterial as its illegality. The game is hard, and players have millions of reasons to pursue something, anything, that might make it easier.

It has always been this way, although the relentless and not-at-all novel pursuit of an edge seems a bit more colorful when it involves a hopeless pitcher on the even-more-hopeless Miami Marlins getting caught on camera drooling onto a baseball. The spitball and its myriad cousins—pitchers have Vaseline’d, sandpapered, thumbtacked, and pine-tarred baseballs for a century and more—are illegal, and players are suspended when they’re caught in the act. But if seeking a pharmaceutical edge is broadly a reflection of the same old and fundamentally human impulse that leads dead-armed pitchers to slather their hat brims with Vaseline, it’s clearly one that Major League Baseball views as a more serious threat to the game. The frankly discomfiting and possibly self-defeating zeal with which commissioner Bud Selig has pursued the case against Bosch and his alleged clients is proof.

In his reporting, Quinn—an ace reporter specializing in PED-related stories—reveals the extent to which MLB has worked to build a case against the players whose names (and, in some instances, code names) appear in Bosch’s records. Bosch had long denied any illegal behavior, which left the names in his notebooks as, well, nothing more than the names of various baseball players scrawled in the notebooks of an ethically challenged sketchball so prototypically Floridian that he might as well have stepped out of a Charles Willeford novel with syringe in hand. To secure Bosch’s cooperation, MLB sued Bosch, tried to get federal agencies to bring charges against him—Quinn reports that the DEA turned down MLB not once but twice—and promised him protection against its lawsuit and the league’s assistance in any future prosecution. The deal that finally flipped Bosch, Quinn writes, included an agreement to “drop the lawsuit [MLB] filed against Bosch in March; indemnify him for any liability arising from his cooperation; provide personal security for him and even put in a good word with any law enforcement agency that might bring charges against him.”

The determination apparent in that seven-layer dip of inducements is even more obvious in the penalties the league reportedly plans to pursue, including 100-game suspensions for players such as Braun and A-Rod. That’s usually the penalty for a second offense, with the two offenses in question here being more or less concurrent. The first was simply associating with Bosch, and the second was denying any association with Bosch when questioned about it by MLB.

You’ll notice that what’s missing in that list of offenses is, not to put too fine a point on it, any real offense—that is, a positive test or any other evidence that the players in question broke the rules. A clause in the Joint Drug Agreement allows the commissioner to suspend players if he has “just cause” to believe they were in violation. An appeals process also allows accused players to confront and question witnesses before an arbitration panel. So this might get even more interesting as it works itself out, and perhaps doubly so for those who’d always dreamed of watching A-Rod, like a buff, frosted-tipped Matlock, cross-examine a witness.

There’s something extraordinary and not a little self-defeating, as SB Nation’s Steven Goldman notes, in Major League Baseball’s quest to bring some of its most recognizable stars to justice for alleged crimes that seem awfully hard to prove, possible consequences and near-guaranteed and highly public awkwardness notwithstanding. But it is, maybe, not that surprising.

It’s one thing for MLB to do what it deems necessary to maintain the game’s fairness. That’s a goal everyone can get behind, give or take a few crossed fingers. But if Selig and Major League Baseball are out to protect the “sanctity of the game,” they’re doomed to lose and lose and lose again, and not just because their janky star witness is basically someone Carl Hiaasen would’ve edited out of one of his novels. Baseball should be fair, of course. But it has never been sanctified, no more than any other human pursuit, from sports to politics. We can believe what we want to believe—that HGH will add some extra miles per hour to a fading fastball; that cheating can be regulated out of human endeavor; that what’s in that dicey-looking packet next to the Newports does what it says it will do. But we’d do well to remember one bigger, truer thing: there’s always enough human folly to go around.

Selig and Major League Baseball seem to be after an overdetermined, semivindictive, specific-unto-bespoke type of justice here. They don't seem to have thought about what would happen if they get it.