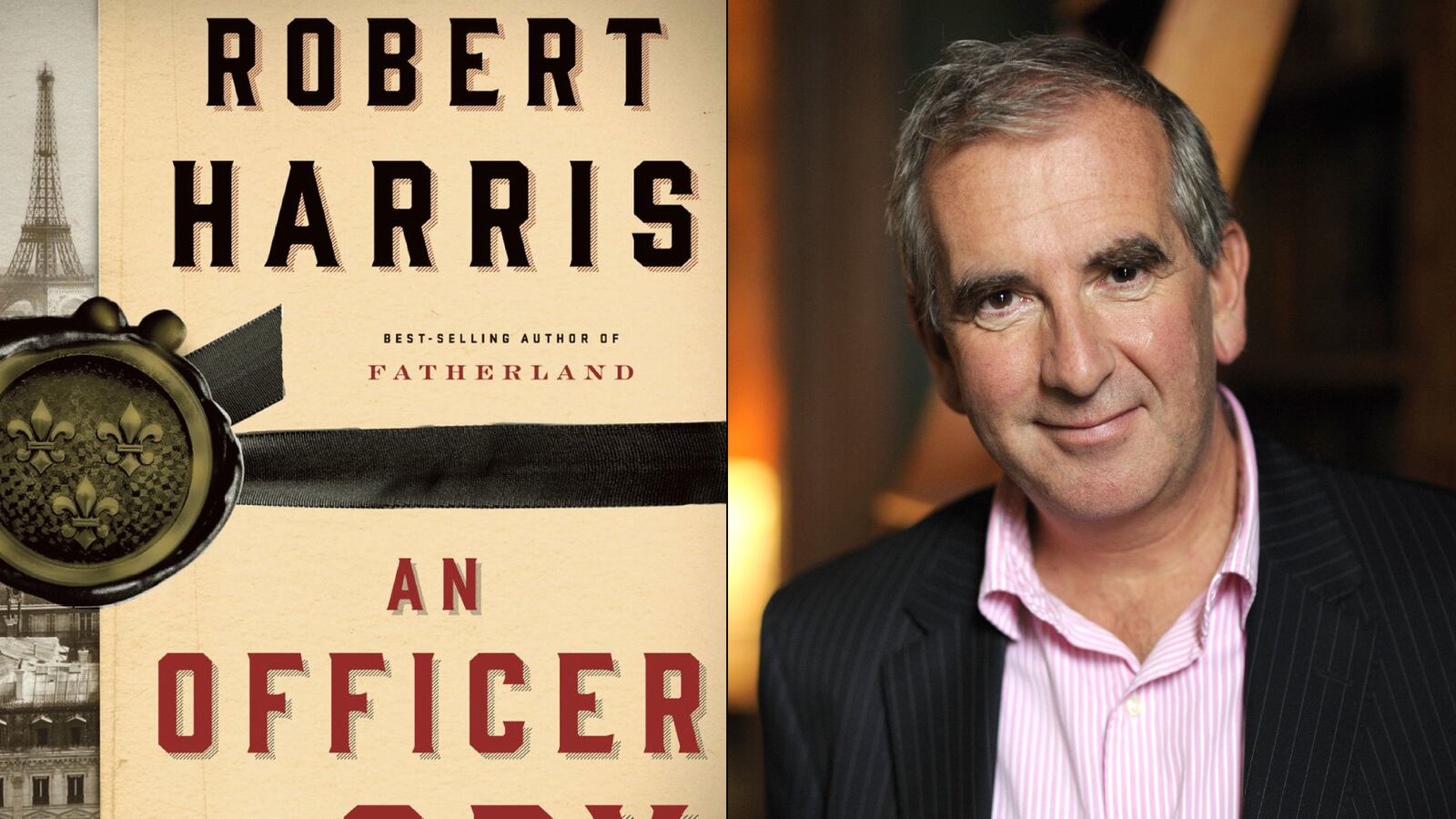

Nothing is more difficult than writing a “historical novel” about a real event (and real people), and few people are better at it than Robert Harris, the author of Fatherland. One problem with this kind of fiction is that all but the most ignorant reader knows how things turned out in the end, there are no surprises. In the case of his new book An Officer and a Spy the subject is the Dreyfus affair, so we know before opening the book that Dreyfus will be found guilty and that eventually, after nearly a decade, his name will be cleared—there have been innumerable books about “the Affair,” and even a movie (actually, by my count there are at least sixteen movies about the Affair, including the most famous one, made in 1937 and starring Paul Muni as Emile Zola, the firebrand French novelist whose accusations against those who had connived in finding Dreyfus guilty help free him), so the element of suspense, one of the most valuable tools of the novelist, is entirely missing.

Some historical novelists use a fictional narrator to guide the reader through the historical past, but Harris, like Hilary Mantel, does without one—his central figure and narrator is Marie-Georges Picquart, a professional army officer who knows Alfred Dreyfus and is a witness to the latter’s famous degradation. Selected to replace the head of the French Army’s counter-espionage department, Picquart inherits the documents that were used to find and convict Dreyfus of espionage, and gradually becomes convinced that far from proving Dreyfus guilty, they demonstrate his innocence of the charges against him—and expose the existence of a real traitor, Major Charles Esterhazy, and worse still the connivance of the most senior officers in the French Army in placing the blame on the wrong man, and then patching together an elaborate “cover-up” to protect themselves and the reputation of the Army.

Whatever he may have been like in real life, Harris succeeds in making Colonel Picquart a likeable and believable character—indeed he is the center of the novel rather than Dreyfus, who for most of the book is far away on Devil’s Island, kept in abominable and shameful conditions, his mail read and censored, his remote hut on the tiny island a kind of tropical hell of heat, insects and enforced silence. Not a likeable or engaging man, Dreyfus has only three things that keep him clinging to life—his devoted and intelligent wife, Picquart’s growing determination to reveal the proofs of his innocence, and Dreyfus’s unwavering faith in his own innocence, even in inhuman conditions that might have driven any other man mad with grief and rage.

Very cleverly, Harris has not made this “a period piece.” Effortlessly, he convinces us that these people are French, that the time is 1895 to 1906, but there is no attempt to create a phony French atmosphere, always off-putting in a novel, like a phony French accent in a film. Instead, he presents us with an altogether familiar reality, a government cover-up, not so very different from Watergate really—it is a novel about espionage, conspiracy, media manipulation, political scandal and the overwhelming desire of the military top brass to save face at any cost. The result is that the book reads like a very modern, contemporary story, not like a “period piece” or the retelling in “faction” form of a familiar historical incident. Except for the absence of television it is all alarmingly familiar.

Having said which, Harris must also be congratulated for the way in which he creates a crisp, fast-paced drama, and his brilliant gift for creating believable characters. Picquart is bluff, smart, stubborn, courageous, horrified at the conclusion his own largely unauthorized search through the files of the office he commands gradually leads him to, his dilemma is that of an honest man being asked to condone a web of deceit, and who cannot do so, even though he knows it will jeopardize his career. He is “a whistleblower,” to use a term which did not then exist, and one by one he uncovers the complicity and guilt in the men he commands and those above him, all the way to the top.

He is, in the most sympathetic way, a man with a conscience, a brave soldier who leads a busy social life, reads Proust, has a married mistress, and whose life seems successful and settled until he begins to look at the files, and begins to explore them reluctantly, appalled to realize that he has put everything he values at risk, but nevertheless determined to go on.

Now that the brilliant John le Carré has long since given up writing about the secret worlds of intelligence and counter-intelligence in favor of novels of ideas, apparently written out of vague anti-Americanism and anti-big corporation feelings (it’s hard to be a master spy novelist once the Soviet Union has been removed as the enemy), Harris has, with this novel, taken his place as the master of making documents and scraps of paper, the details of painstaking intelligence work, into drama. Those reading this book will need to keep their wits about them as Harris introduces the famous letters and that served to incriminate Dreyfus, as if they were doing a crossword puzzle. But part of the entertainment lies in these tantalizing bits of papers, some artful forgeries, that having served their purpose are filed away, intended never to be seen again, except that Picquart can’t stop digging them out, studying them, at first out of curiosity, then out of a determination to know the truth, hardly caring that he will bring down a government, derail his career, expose his love affair with a married woman, and set off the chain of events which led to Zola’s famous article “J’accuse!” and to the eventual exoneration of Dreyfus.

With a rich cast of characters, a perfect ear for dialogue and an awesome command of the Dreyfus Case in all its perplexing detail he has written a novel that is at once exciting reading and surprisingly informative. If you don’t know anything about the case, you will emerge knowing as much about it as anyone can, and if it’s old familiar ground, you will emerge astonished at what a rich stew Harris has made of these dry old bones, and wondering whether it isn’t time for a new movie about Dreyfus, with Picquart, as he was in real life, the hero.

From one of the great scandals of the late 19th century, Harris has written a novel which is true to the facts, scrupulously so, but reads like a combination of Le Carré at his best and Conan Doyle writing about Sherlock Holmes. I could have wished it longer, and am dying to know what he will do next.