The key to why MJ (booking to Sept 4, Neil Simon Theatre) is such a disappointing piece of theater—for all its visual dazzle and fantastic singing and dancing—is there in the program: “By special arrangement with the estate of Michael Jackson.”

There is nothing surprising in the show, which opens tonight on Broadway. This is a slickly corporate, officially sanctioned slice of legacy clean-up. Two and a half hours of glittery hagiography. If you expect a musical that examines Jackson’s life, controversies, and legacy, forget it. If you want to see anything which even mildly challenges the deification of Jackson, or interrogates his celebrity and actions with depth and nuance, this is not the show for you.

If you want to hear a bunch of Jackson’s most famous (and not that famous) songs stitched together with a colorless lack of plot: roll up. You will hear renditions of “Bad,” “Beat It,” “Billie Jean,” “Man in the Mirror,” “Thriller,” and many more so thunderous the beat vibrates in your chest cavity. You’re going to get the glove, the moonwalk, everything that Michael Jackson is loved and lionized for as a performer.

And it is Jackson the performer, not the person, MJ is squarely focused on. As evident from the audience’s response at a recent performance, MJ will be loved by the Jackson faithful—and perhaps that is enough for it. Reviews like this won’t matter; its audience doesn’t want to hear a bad, or even vaguely doubtful, word said about its subject, and its producers hope his most devoted fans will supply the reservoir of ticket buyers. It is far from alone when it comes to unimaginative karaoke nights dressed up as Broadway theater shows. Fan worship is their beating heart.

The show, with a book by Pulitzer winner Lynn Nottage, is set in rehearsals in a Los Angeles studio for Jackson’s Dangerous tour in 1992, which gets the musical off the hook when it comes to confronting the allegations of child abuse made against the star, beginning with Jordy Chandler’s accusations the following year. Instead, there are references to “allegations,” whatever that refers to. He is seen popping pills for pain resulting from the infamous incident when his hair was set on fire while filming a Pepsi commercial years before.

His astonishing achievements as a Black artist are rightly celebrated, especially in the context of a white America all-too-primed to denigrate Black success. MJ rightly and emphatically states the significance of that success. When asked about his lighter skin color, the Jackson on stage, just as the Jackson in real life, says that its pigmentation comes from vitiligo.

A documentary crew from MTV has been created (a producer called Rachel played by Whitney Bashor, and a cameraman, Alejandro, played by Gabriel Ruiz), whose mildly questioning presence—truly, they are the world’s worst journalists—is seen as a threat. How they are presented says everything about how the media is seen by Jackson’s estate. But they do nothing substantial in terms of revealing anything juicy, despite their stated intent that that is precisely what they are setting out to do. They just kind of hang around, quite clearly not getting the story.

Their lack of editorial inquiry raised, for this critic at least, the specter of exactly the same off stage. Did nobody in the planning of MJ want to go any deeper than the extremely basic song-and-danceathon that has come out of the sausage grinder? Did nobody else think this one-note show might seem a little inadequate? Will every MJ Playbill come with its own amnesia pill? It is not a stroke of genius to excise and erase the last 17 years of Jackson’s life. It is an act of narrative neglect.

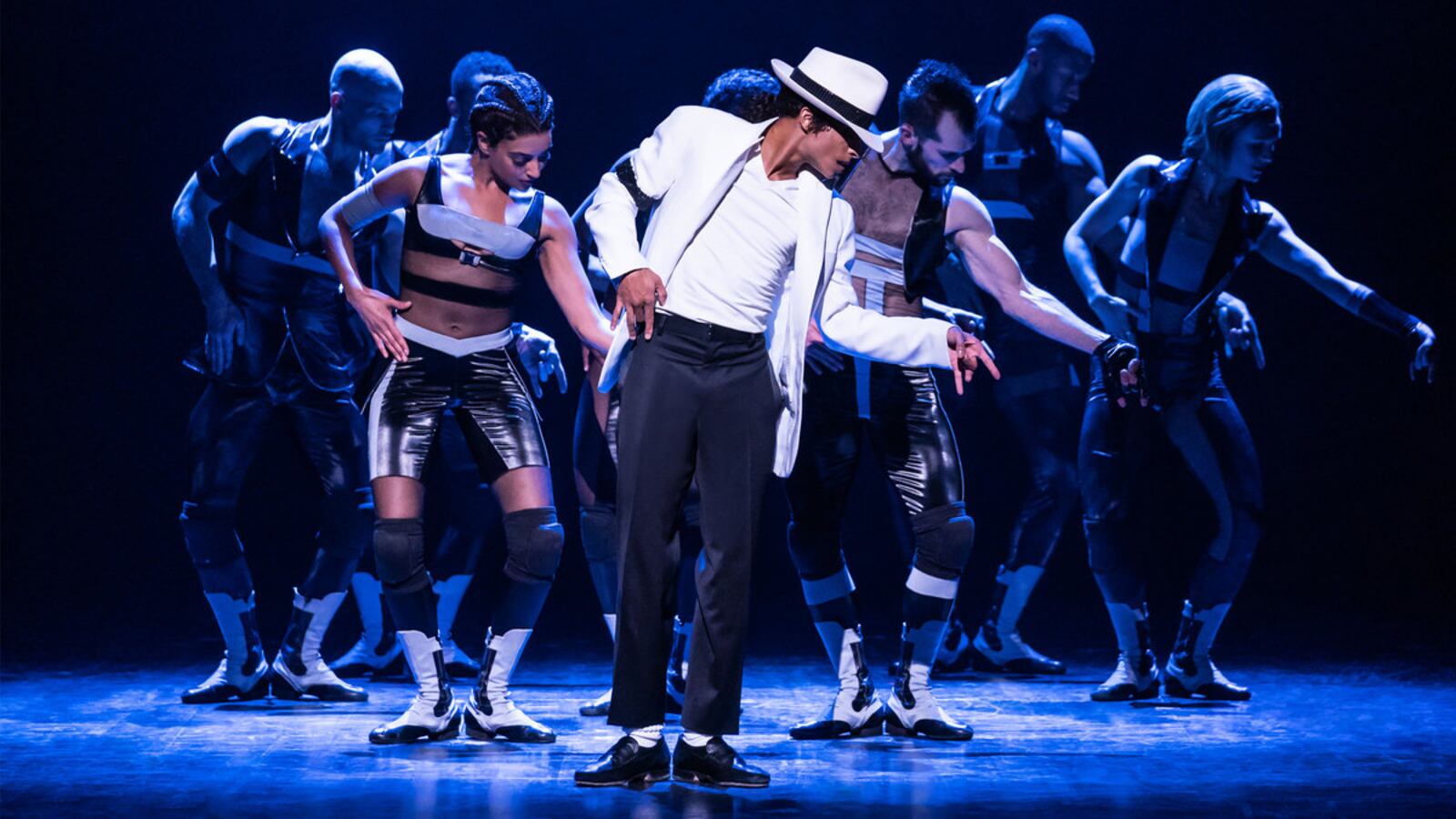

Myles Frost plays Jackson as an adult, and absolutely nails the dance moves and whatever singing he is doing, and that fluttery voice. We see Jackson wanting to soar above the stage despite the costs of such technical wizardry.

He reveals nothing that already isn’t known, or easy to Google. Here again is the story of the brutal dad (Quentin Earl Darrington), who wants Michael to succeed at all costs, and forever to be in his debt.

If the show is meant to be complimentary about Michael Jackson, then it is pinning a lot on the charms of its lead. But just as we strain to hear him, so we also strain to understand him. In the rehearsal room, he just seems to be a nightmare perfectionist, who cares only about himself, treating with absolute disdain the managers and off-camera people who keep his madcap circuses on the road.

Myles Frost as Michael Jackson in 'MJ.'

Matthew MurphyMJ shows Jackson as both supreme performer and diva nightmare, demanding things, threatening to have loads of people fired if his demands are not met, and then a moment later blithely apologizing and saying he values everyone and just wants everything to be great. Perhaps this is supposed to denote his creative genius, but because of the thinness of the story, Jackson too feels oddly insubstantial when he is not singing and dancing up a storm. He is also painted as a victim—of his father and the media. There is half-hearted conflict with his brothers, who feel lousy about being left out in the cold.

The story—or cobbled-together series of well-worn biographical entries—flicks back to Jackson’s childhood, and two younger Michaels. One is played by Christian Wilson and Walter Russell III at different performances, with slightly older Michael played by Tavon Olds-Sample. To be clear: their singing and dancing on stage, is wonderful—and the rest of the company too. But this is a spinoff pop concert, and overlong at nearly two and a half hours.

There is no story here. No tension. It is odd to have Darrington play the brutal Joe, and the stern but kind Dangerous director Rob. Why some lead characters seem to stay on stage and randomly sing along, like Rachel the documentary producer, is a mystery. One performer stands out above all others: Ayana George as Katherine Jackson, whose voice is so smooth and superlative it soars above the show.

MJ ends with “Thriller,” which looks like the most amateur part of the night, with crap zombie costumes that resemble walking trees. The audience, by now in raptures, doesn’t care. MJ has done its greatest-hits best. Jackson, the program says, “is one of the most beloved entertainers and profoundly influential artists of all time.” But that is not the full story of his life or image—and this high-voltage musical is a cynical grab for dollars, as well as yet another depressingly empty Broadway celebration of celebrity.

Prayer for the French Republic, Joshua Harmon’s play about history, family, identity, and how overly maligned Israel is, is three hours in duration (booking to February 27). This Manhattan Theatre Club production, which opens tonight, has two intervals, and a brilliant group of actors who have somehow mastered its many crashing waterfalls of speeches and arguments—and do it twice on Saturdays. Not all of it coheres, and much of it is repetitive. Yet the play, directed adroitly by David Cromer, when it is not stuck one of its many didactic spirals, is also moving and funny as it switches between its two historical time periods.

In Paris of 2016-2017, the Benhamou family—mother Marcelle (Betsy Aidem), Charles (Jeff Seymour), and Elodie (Francis Benhamou) find themselves hosting a distant American cousin (Molly Ranson). She seems to be a cuckoo in the nest, but her presence is soon subsumed into a crisis. Son Daniel (Yair Ben-Dor) has become a bloodied victim of anti-Semitic violence, and from this unfolds a tale of a family questioning how safe they can be in France, especially in the wider political and cultural context of anti-Semitic rhetoric and violence, and political ascendancy of Marine Le Pen’s far right party. A lone piano binds both narratives, as does the fate—back then and right now—of the family’s piano-selling business.

Nancy Robinette, Kenneth Tigar, Ari Brand, Pierre Epstein, Peyton Lusk, and Richard Topol in 'Prayer for the French Republic.'

Matthew MurphyIn another four walls in Paris in 1944-46, we meet Irma and Adolphe Salomon (Nancy Robinette and Kenneth Tigar). Somehow they have managed to stay safe in the Nazi-occupied city, while the fate of their children is unknown.

Later we will meet their son Lucien (Ari Brand) and his son Pierre (Peyton Lusk), the latter whose care in the later years (as played with a lovely growling solemnity by Pierre Epstein) is a chief cause of concern for Marcelle and brother Patrick (Richard Topol), who acts both inside the play as an antagonist challenging his sister—over how visible a Jew she needs to be—and as a narrator taking us through history. What price safety? What price love? What do politics and ideals mean? What do we know of ourselves? What happened to the real people of the past whose names we invoke with a shaky grasp of who they were?

No summary of the play can do justice to its many textures and modulations, but they pierce most effectively when focused on the witty and serious interactions of family members rather than its pro-Israeli invective (most volubly expressed by Elodie in one cascading diatribe—a standout rhetorical feat of Benhamou’s aimed at Molly). This play isn’t shy about stating views. It does not hide behind words or symbols. It ends with a death made beautifully lyrical, and it is lovely to see its sprawling kind—for good and occasionally bad, it commanded this critic’s attention throughout—back on the New York stage.

Kearstin Piper Brown and Justin Austin as Esther and George in 'Intimate Apparel.'

Julieta Cervantes and T. Charles EricksonIntimate Apparel is the first opera to be produced by New York City’s Lincoln Center Theater (booking to March 6), and its first production resulting from the Met/LCT New Works Program. It follows, tenderly and beautifully sung, the travails of Esther (Kearstin Piper Brown), a maid who is good and hard-working, who falls—long-distance, via letter—with a man who will eventually become her husband. But George (Justin Austin) is not the man she thought she was writing to, and so she is faced with the question of how to stay in, or leave, a marriage that is terrible for her. Staged on one of Lincoln Center’s smaller stages, this story finds a concentrated focus.

Make sure you pick up a copy of the Lincoln Center Review when at the theater; it relates the story of how Lynn Nottage came to write the play Intimate Apparel, which has now been set to opera. It helps make sense of the two images we see at the end of act one and at the end of the play—images of Black women that Nottage and composer Ricky Ian Gordon have both brought to life and endowed with presence and meaning.