For a time, John Paulk was the most famous ex-gay person in the world.

Throughout the ’90s, he was the public figurehead of the ex-gay movement. He was on the cover of Newsweek, a coveted guest on the talk-show circuit, and frequently booked to speak at religious conventions. He and his wife, Anne, used to be gay. Then they “found God,” and each other.

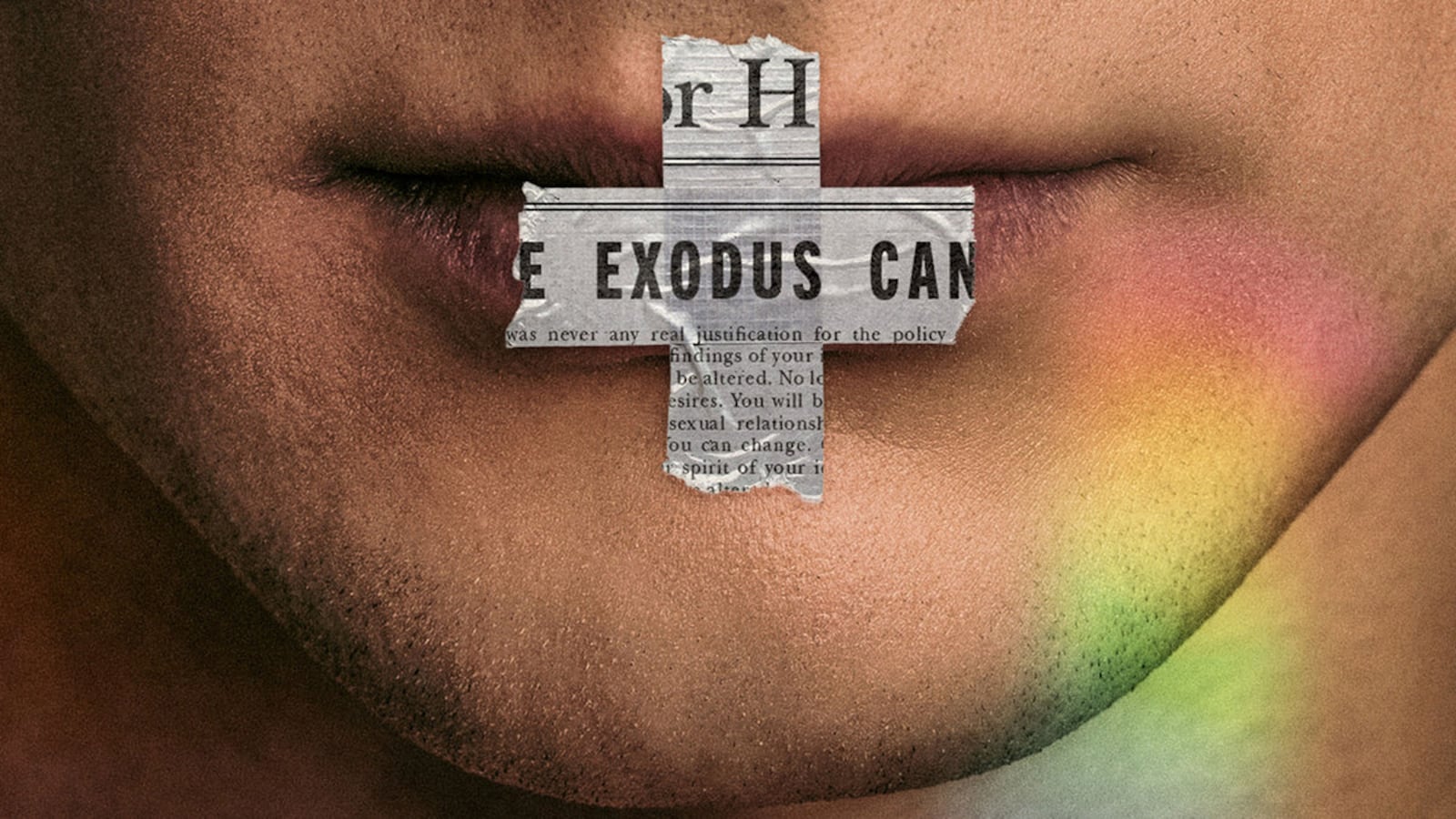

Paulk become a devout and active member of Exodus International, an umbrella organization that connected different groups across the country that were all in pursuit of helping people with “homosexual desires” who wanted to rid themselves of those inclinations and become closer to God. At the crux of these groups is the idea that homosexuality is sick and sinful.

With the help of what is commonly referred to as conversion therapy, they could return to the path toward goodness, toward God, and away from their homosexual urges. Paulk was the proof, a success story.

In 2013, Paulk disavowed Exodus and the idea of conversion therapy, apologizing for his role in promoting it for so many years. He no longer identifies as “formerly gay.” He is gay.

Paulk is among the former participants in the ex-gay movement and leaders who are interviewed in the new documentary on Netflix called Pray Away, which was directed by Kristine Stolakis and executive produced by Ryan Murphy and Jason Blum.

In talking to these leaders and survivors of conversion therapy, Stolakis chronicles the trauma and pain inflicted by these groups and examines how organizations like Exodus International manipulated people’s faith and desire for a relationship with God to convince them to “pray away” their homosexuality.

“I think a particularly dark part of this movement is that it combines religion and people's connection with something greater with pseudo psychology,” Stolakis tells The Daily Beast. “When you grow up in a community where you’re getting a message that you are sick and sinful, there is tremendous motivation to want to try to change that.”

Stolakis grew up in a Catholic family and learned that her uncle had gone through conversion therapy. For much of his adult life, he experienced depression, anxiety, ideations of suicide, obsessive compulsive disorder, and addiction. Part of the reason she wanted to make Pray Away was to have a better understanding of why, for so many years, he had continued to believe that he could change—or “convert”—and participate in a belief system antithetical to who he was.

“I really think a lot of the public doesn't understand this movement unless you live in one of these communities,” Stolakis says. “And if you live in one of these communities, it's like the air you breathe.”

It’s estimated that approximately 700,000 people have gone through a form of conversion therapy in the United States. A national survey found that LGBTQ youth who experienced conversion therapy were more than twice as likely to attempt suicide.

Activists have worked hard to push politicians to ban the practice, and have been successful in passing legislation in several states making it illegal. But those bills only ban the practice from licensed therapists. Where this has always been happening, in the church and in religious communities, it still thrives and is protected by law.

“This is a message that we hope our film sends, which is that as long as some version of homophobia and transphobia exist, some version of the conversion therapies will continue,” Stolakis says.

It was important for her to feature leaders of the ex-gay movement who have since apologized for their involvement and spoken out about its harm; she wanted to show current leaders and organizations that there is a path out. But even if influential organizations like Exodus International have shuttered, the movement is as strong as ever.

“I wish I could say something rosy, that this collection of leaders has defected, therefore this is going away,” Stolakis says. “It’s not the case. There are always going to be new leaders essentially in training, ready to take this place if this larger culture of homophobia and transphobia continues.”

A crucial voice in Pray Away is that of Julie Rodgers, who was a teenager when she started working with Living Hope, an affiliate ministry of Exodus International. She grew up in a conservative Christian family that was heavily involved in the church. When she was 16, she came out as gay to her mother, who became frantic and eventually got her daughter a meeting with Rick Chelette, the executive director of Living Hope.

Chelette promised Rodgers’ family that he would “heal” her, in part by identifying something in her past—sexual abuse, strained relationships with a parent—that gayness could be “blamed” on.

Rodgers eventually became so involved with Living Hope that she would move into a live-in recovery house and rise to become one of its most popular speakers, traveling the country to preach about her journey and endorse the organization. “My whole entire life was structured around not being gay,” she says.

She was told to give up porn and playing softball, and to wear more makeup to feminize her appearance. She felt compelled to confess every lesbian urge and lapse in gender expression to Chelette. But when she was sexually assaulted while in college, no one at Living Hope or at Exodus offered help or counsel. They seemed largely at a loss with what to do about it. It’s then she realized that this wasn’t a community. She was being used as a prop, molded from a young age when she was emotionally vulnerable.

When she first watched the finished Pray Away film, she struggled while listening to former leaders, many of whom she knew personally and once spoke alongside at religious conferences, coming to terms now with all the pain they caused and grappling with the fact that they have blood on their hands.

“I have really been trying to remain open to their humanity,” Rodgers says. “It’s really, really hard being human. I know that and I know that nobody benefits by me relitigating their past behavior. All I can do is meet them where they are now. We don’t have to be best friends, But we do have the shared goal of wanting nobody else to go through this. I wish they had wanted it 10 years earlier. All that matters is what they’re doing today.”

Rodgers is now married to her wife, Amanda. Their wedding was in a church that embraces the LGBT community. “It was really redemptive to be in this place where that has been a source of so much shame for me and Amanda both,” Rodgers says. “To have all these people come around us and celebrate us and celebrate our love, specifically our gay, lesbian love in that space. And for a priest to be like, ‘OK, y’all kiss now, right here at the altar,’ it was so incredibly healing and redemptive.”

Stolakis and Rodgers’ urgency in making Pray Away stemmed in part from a desire to battle the assumption that in 2021, when “woke” and “inclusivity” are buzzwords, practices like gay conversion therapy don’t exist anymore. When pop culture turns the concept of gay converstion therapy into a joke, as shows like Saturday Night Live have done several times in recent years, it fosters an assumption that, because it’s being laughed off, it must not be a serious problem in modern society.

Anecdotally, they’ve observed the opposite. The more progressive certain parts of society become, the more aggressive and protective these communities are of what they consider to be morally upright and pure lifestyles.

“There’s definitely a sense in which we are seeing polarization and we are seeing more people that I’m connected to still in the Christian right really digging their heels and doubling down,” Rogers says, adding that Living Hope is larger and more influential than ever.

“I think it is a mistake if we look at this as a red versus blue issue, as Republican versus Democrat,” Stolakis says. “This is not that. We’re talking about making sure people are more or not more likely to kill themselves. That’s what we're talking about. There’s no room for politics. We need to make sure that people are safe.”