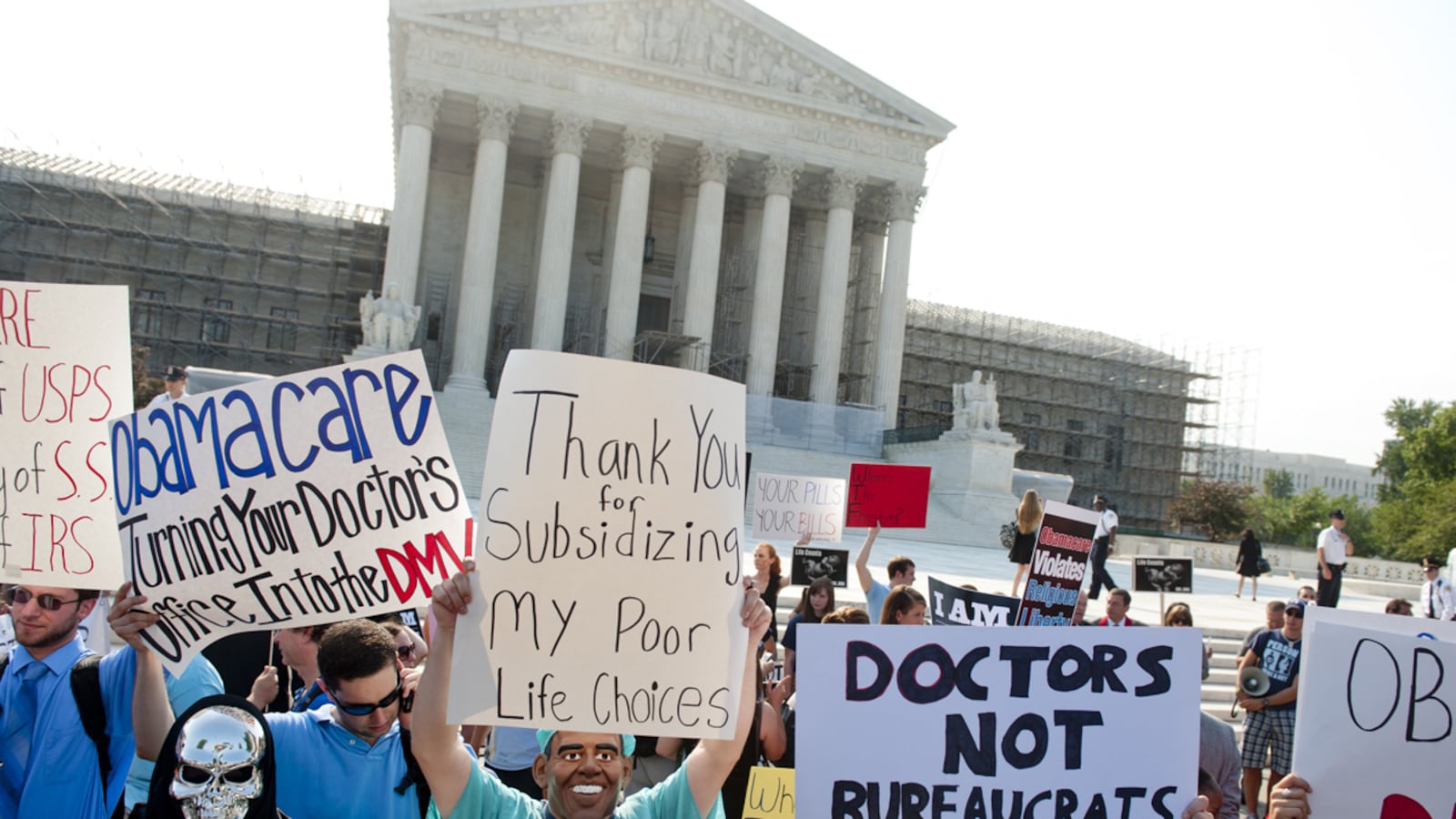

It’s easy to see why liberals are relieved today: the most important progressive legislation of most of our lifetimes has survived. It’s easy to see why centrists are relieved: the Supreme Court’s legitimacy has survived. Centrists understand that it’s not a good thing for an ostensibly nonpartisan institution like the Supreme Court to be at war with one of America’s two major parties. John Roberts has made sure that didn’t happen, and as a result, the court’s legitimacy is no longer in free fall.

Conservatives, by contrast, are livid. As with abortion, ostensibly conservative justices, appointed by ostensibly conservative presidents, have upheld policies that most conservatives hate. But take it from a liberal, thoughtful conservatives should be relieved too. For one thing, Roberts has proved that at least some conservatives really believed all that talk about judicial restraint. The conservative movement has been most successful when it balances its desire to repeal progressive change with a principled belief in the value of conserving things, even things right-wingers dislike. That’s what Dwight Eisenhower understood when he imposed fiscal discipline on Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman’s newly created welfare state rather than trying to repeal it. It’s what Ronald Reagan understood when he set a more traditional tone for the country rather than directly challenging the new freedoms of the 1960s. In the Tea Party era, the GOP has become too revolutionary and insufficiently conservative. It has lost the modesty that true conservatism should have at its core. From the bench, Roberts has shown how to restore that balance.

Finally, Roberts has prevented conservatives from succumbing fully to the temptation that so badly damaged liberals in the 1960s and ’70s: the temptation to win in the courts what you can’t win at the polls. In the ’60s and ’70s, as the Democratic coalition crumbled, liberal activists increasingly turned to the courts to extend progressive change. In so doing, they prevented themselves from having to reckon with the reasons that so many voters were turning against their policies. Overreliance on the courts made liberalism more elitist. And it made the conservative backlash of the Nixon and Reagan eras more intense—because if there’s one thing Americans hate more than unpopular policies, it’s unpopular policies imposed upon them by unelected courts.

Now, because of Roberts, conservatives will have to defeat Obamacare the hard way: by defeating Barack Obama. If Mitt Romney wins this fall, and Republicans grow stronger in Congress, the GOP will be able to significantly undermine Obamacare legislatively. If, on the other hand, Obama wins despite a lousy economy and public ambivalence about his signature domestic achievement, Republicans will have to ask themselves hard questions about their unpopularity among the fastest-growing segments of the American electorate. In the long run, that will be good not only for American democracy, but for American conservatism. And one day, perhaps, the conservatives who today revile John Roberts will give him his due.