For the second time in 33 days, President Joe Biden gathered the nation on Monday to mourn a loss it can no longer fathom, to collectively grieve after a year of grief beyond imagining, as the nation’s death toll from the coronavirus pandemic officially crossed half a million people.

“We often hear people described as ‘ordinary Americans,’ but there’s no such thing,” Biden said, standing in the Cross Hall of the White House. “The people we lost were extraordinary.”

The pandemic year has seen more deaths, as the president noted in a proclamation commanding all U.S. flags be flown at half-mast until sundown on Friday, than the number of Americans who perished “in World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War combined.”

“That’s more lives lost to this virus than any other nation on earth,” Biden said. “They’re people we knew. They’re people we feel like we knew… The son who called his mom every night, just to check in. The father’s daughter who lit up his world. The best friend who was always there. The nurse—the nurses—the nurse who made her patients want to live.”

Biden, whose life and public service has been defined by moments of deep grief, urged Americans to learn from his losses, to “resist becoming numb to the sorrow” of an empty seat at the dinner table.

“I know all too well,” Biden said, appearing to keep back tears as he spoke. “I know what it’s like to not be there when it happens. I know what it’s like when you are there, holding their hands, as you look in their eye as they slip away.”

Biden concluded his remarks by asking Americans to “find purpose” in their grief, a purpose worthy of the lives lost in a terrible year.

“This nation will know joy again,” Biden said, before making his way to the candlelit South Portico, where the U.S. Marine Corps Band played “Amazing Grace.” The National Cathedral, 15 minutes away, had just finished tolling its 12-ton Bourdon Bell 500 times, once for every thousand lives lost in the United States. “We will get through this, I promise you.”

With the first lady, the vice president and the second gentleman at his side, each wearing a black face mask, Biden then led the country in a moment of silence to reflect on the darkest moment of the “dark winter” he’d warned would come. It was 100,000 more deaths since he last told the nation in January, on the eve of his inauguration, that “to heal we must remember,” and 200,000 more than when he told Americans in December that his heart went out to those about to enter the new year “with a black hole in your hearts—without the ones you loved at your side.”

The ceremony was, of course, largely symbolic. The nation’s death toll from the coronavirus pandemic almost certainly crossed the 500,000 mark weeks ago—excess deaths remain roughly 20 percent higher than the official death toll—and the total number of lives lost to the virus will probably continue to rise long even after the pandemic has finally receded, given the upwards revision of estimated death tolls for past pandemics.

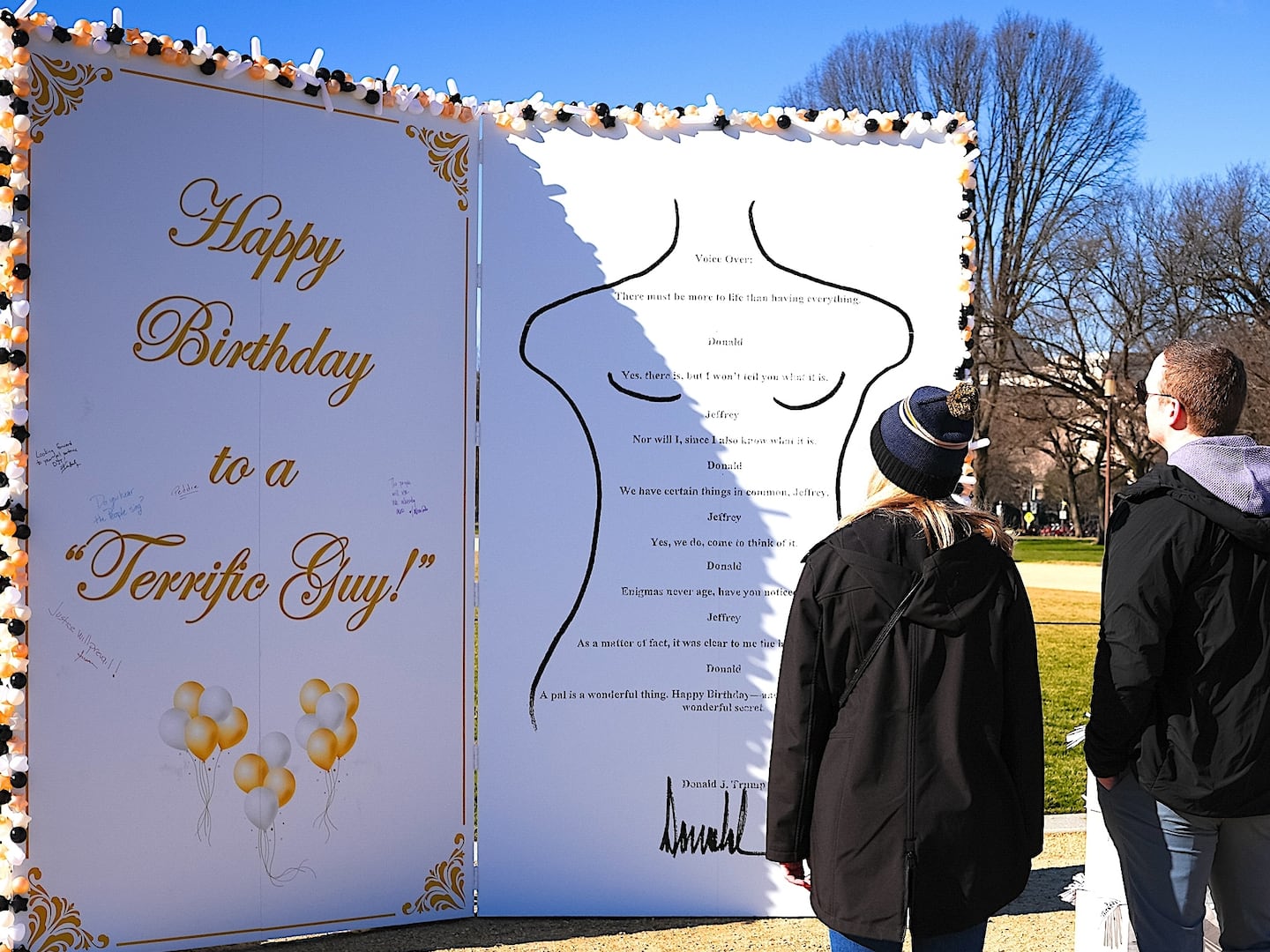

What the moment did mark, however, is the cementing of the pandemic—and the government’s response to it—as Biden’s responsibility. Yes, he was left a national response that was in worse shape than he could have imagined, with millions of missing vaccine doses and an anti-inoculation movement that has run rampant on social media. His predecessor had lost interest in addressing the pandemic months before his term ended, turning attention to an unsuccessful coup attempt that his own task force warned would cost American lives.

But no president, alone in his thoughts during a moment of silence remembering 500,000 dead citizens, can plausibly go back to repeating the White House’s line from earlier days that he’s “only been here three and a half weeks,” or “only been here three weeks,” or “only been here two and a half weeks,” as White House press secretary Jen Psaki had told reporters in the last week.

It took weeks for the Biden COVID-19 task force to get its footing. For the first several days, the administration struggled to explain exactly how it would get vaccinations moving and why states across the country were canceling appointments en masse. Officials offered various answers, including that the administration was still trying to locate millions of doses and that the Trump administration had left them with a broken distribution playbook. In that time, thousands of people died, many of whom were infected before Biden took office. Still, the talking points at most press conferences on COVID-19 over the last several weeks have focused on the fact that case and death numbers across the country are steadily decreasing.

While the nation’s vaccination rate is improving and the administration has inked new deals with pharmaceutical companies to ensure doses flow throughout the next several months, health officials are still concerned about the emergence of new variants. Officials say while data suggests that the vaccines available to Americans work well against the United Kingdom and South African mutations, other, potentially more deadly variants could cause another surge this spring—and further delay any semblance of normalcy in American life.

Back to normal—children attending school in an actual school, adults making face-to-face small talk with colleagues, families eating at restaurants and celebrating weddings and gathering for funerals, and a White House where visitors aren’t tested for a virus as thoroughly as they are for firearms—has never seemed so far away. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the lone holdover from the Trump administration’s beleaguered COVID-19 firmament, appears perpetually on the verge of telling Americans that we’ll never have true “normal” again.

“It really depends on what you mean by ‘normality,’” Fauci said in an interview last weekend. “If ‘normality’ means exactly the way things were before we had this happen to us, I can’t predict that.”

Biden, too, has been cautious not to overpromise on timelines for vaccinations or school reopenings, lest he under-deliver or be thwarted by any number of the many factors beyond his control. It remains a giant question whether vaccinations stop the spread of the virus, or whether children can be effectively vaccinated, which means that “normal” for families will be delayed even longer. A third of people say they won’t get a vaccine, for reasons either understandable and moronic. Other once-in-a-century disasters, like the Texas deep freeze that delayed the delivery of tens of thousands of vaccinations, could further move “normal” out of reach.

The reality of that possibility comes as the nation’s grieving process has moved on from shock and denial and depression to, increasingly, anger. Violence against Asian Americans is increasing across the country. Voters are increasingly desperate that Congress won’t be able to send additional COVID relief to Biden’s desk until mid-March, even as he went the fast route rather than sacrifice, as one Biden insider put it, “two or three months of negotiation” that would have led to “only two or three Republican votes.”

Biden’s focus, Psaki told reporters ahead of Monday’s ceremony, is on passing the American Rescue Plan and ensuring that the nation has enough vaccines to inoculate 300 million Americans against the virus.

“But the American people have a role to play here as well,” Psaki said. “Wearing masks, social distancing. Everybody wants to get back to normal, but the president, the federal government can’t do that alone. It is going to take everybody participating in that process to get closer to normalcy.”