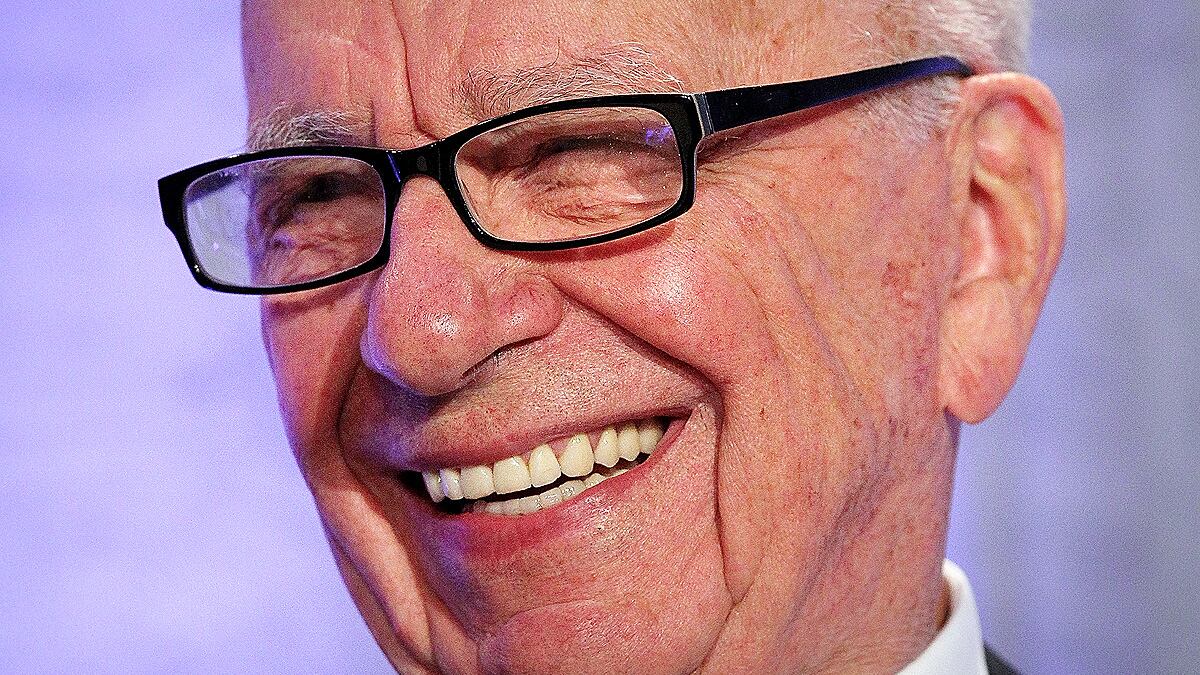

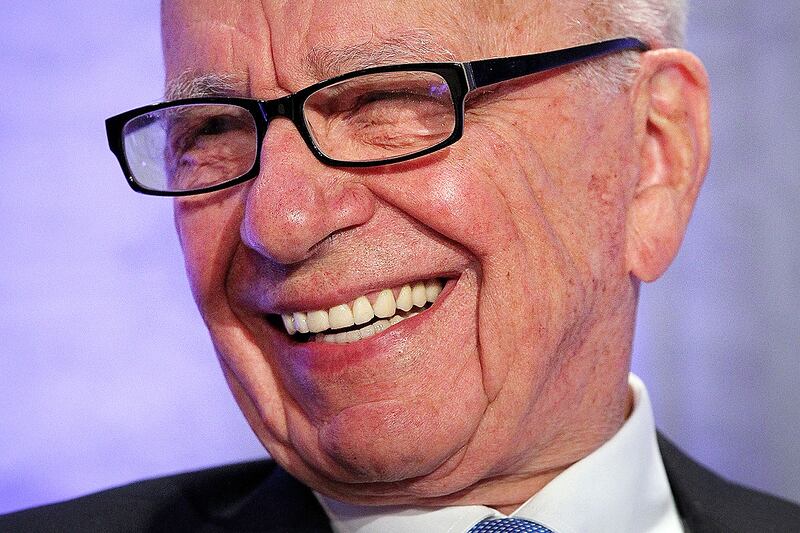

Rupert Murdoch must have hoped that by closely controlling the News Corp. annual general meeting, the first since the widespread criminal activity by his employees hit the world headlines, he would draw a line under the scandal that has engulfed his company. The meeting was switched to the gloom of the Darryl Zanuck Theater in the locked down Fox movie studio, where security guards inside and out outnumbered the 40 or so shareholders by 10 to one.

But if that was his plan, it soon went awry. No sooner had Murdoch repeated what has become his mantra, “There is no excuse for such unethical behavior,” than Tom Watson, one of the British lawmakers who has called the Murdochs to account, pointed out that the big-screen backdrop behind the board members on the dais did not merely celebrate such notable News Corp. achievements as American Idol. It also sported a London Times front page marking the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton.

Did the company not realize, asked Watson, that it was the hacking of the royal couple’s intimate voicemails by Murdoch private eyes that had lifted the lid on what was described by one shareholder as the “industrial strength criminality” going on under his nose? Despite the worldwide brouhaha, it seems that no one in News Corp. has been paying much attention to what another shareholder described as “the pervasive and value destroying scandal,” either before it broke or since.

And so it transpired. Representatives of California pension funds, Christian investors and Australian shareholders took it in turns to demand that Murdoch step down as CEO and chairman and make way for a truly independent figure who would improve the ethics of the company. Even before the debate began, Murdoch told the meeting he would be voting against the motion, and as his friend Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal would be joining him, the motion would be defeated, so there was no need for discussion.

For all the solemn declarations of remorse, Murdoch appears to have no intention of living up to his belief that when it comes to newspapers, “The buck stops with the owner, whether the presses break down, whether there are libels in the papers, or anything else.”

To deflect attention from Murdoch’s son James, who stands accused of perjuring himself before the British Parliament and who must return to be quizzed again next month, he and his brother Lachlan, exiled to Australia, sat in the front row of the theater in an area cordoned off by velvet ropes and policed by guards. Neither James Murdoch, nor the deputy chairman Chase Carey, whom many News investors hope will succeed the old man before long, found it in themselves to say a word to shareholders.

But it was the strange behavior of Rupert Murdoch himself that attracted attention. Before opening the meeting he recited from a script his regret that the scandal had broken without quite apologizing for what had been done in his name or accepting responsibility for the ethos in his company that led so many to believe he would approve of such activity. No sooner had he formally opened the meeting, however, than it became clear he was not chairing it unaided. To his left, in the gloaming, was a man staring straight at the crowd like a secret serviceman looking for assassins. Before long it was this shadowy figure who was not only telling shareholders their time was up but, in one extraordinary outburst, telling “Rupert,” as he called him, to stop talking.

Whether it is because he has enjoyed total control over News Corp. for so long that he has forgotten, or whether he has simply lost the ability to chair a formal meeting, Murdoch made error after error in trying to keep the meeting from sliding into chaos. At times he added to it himself, announcing after a barely whispered prompt and long after debate had begun the conditions on which he would allow the floor to ask questions.

Shortly after the shareholders had begun demanding he step down, he showed his contempt for them by announcing that, debate or not, the voting was now open. To silence a particularly virulent Australian critic, Murdoch peremptorily brought the meeting to an end, only to be advised that he had not followed protocol so must open the meeting again before closing it according to the rules.

And when not banging the lectern to make his point, he kept interrupting speakers with testy, acerbic asides. “That’s not true, but never mind,” was a favorite, though at one point he told Stephen Mayne, the terrier-like Ozzie, “I’m not accusing you of being a liar, but . . . ” He could not resist stopping a representative of the Church of England in his tracks by sneering that the Anglican Church’s investments had shown poor returns. And when a Catholic priest suggested that a company’s ethos always stemmed from the top, Murdoch was indignant, saying he was highly ethical, as were all his newspapers and television stations, and that if the priest wanted to hear more, he would take him to lunch.

So an event that might have put at ease some of the nagging doubts about whether Murdoch had really learned the hard lessons of the last year and was up to reforming morality in the battered company has only delayed the reckoning. By next year’s annual general meeting, the federal investigation into whether his employees broke American law will be well advanced, as will the lawsuit claiming News Corp. overpaid for his daughter Elizabeth’s film company Shine.

Meanwhile, as Watson warned the meeting, a second wave of civil suits in England will soon erupt from News Corp. employing a convicted felon to hack personal computers. There are also civil suits in Britain arising from the hacking of the phones in 2002 of two murdered 10-year-old girls; the parents of murdered schoolgirl Miller Dowler cost $3.2 million to settle. The key question, however, remains whether 12 months from now Rupert Murdoch will still be at the helm at 1211 Avenue of the Americas.

Nicholas Wapshott’s Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics has just been published by W. W. Norton.