Showtime’s new comedy, HAPPYish, wastes no time shocking the system. It opens on a photo of Mount Rushmore, an arrow pointed at the bust of Thomas Jefferson, as Steve Coogan’s cantankerous protagonist Thom Payne rants his voiceover.

“This is Thomas Jefferson, founding father of my adopted home of America,” Payne says. “Which I love with all my heart. But then, fuck, he had to go write that line, ‘Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’”

What could possibly be wrong with that? Thom goes on: “Life, sure. Liberty, I understand the basic concept. But happiness? What the fuck is happiness? A BMW? A thousand Facebook friends? A million Twitter followers? I wish he’d been more honest. I wish he would’ve just said ‘pursuit of happiness, whatever the fuck that is.’ Just don’t keep us guessing, Tom. Guessing, and pursuing, and failing.”

Then, finally: “Fuck you, Thomas Jefferson.” Steve Coogan flips off the camera. A punk-rock version of “If You’re Happy and You Know It” plays.

Welcome to HAPPYish.

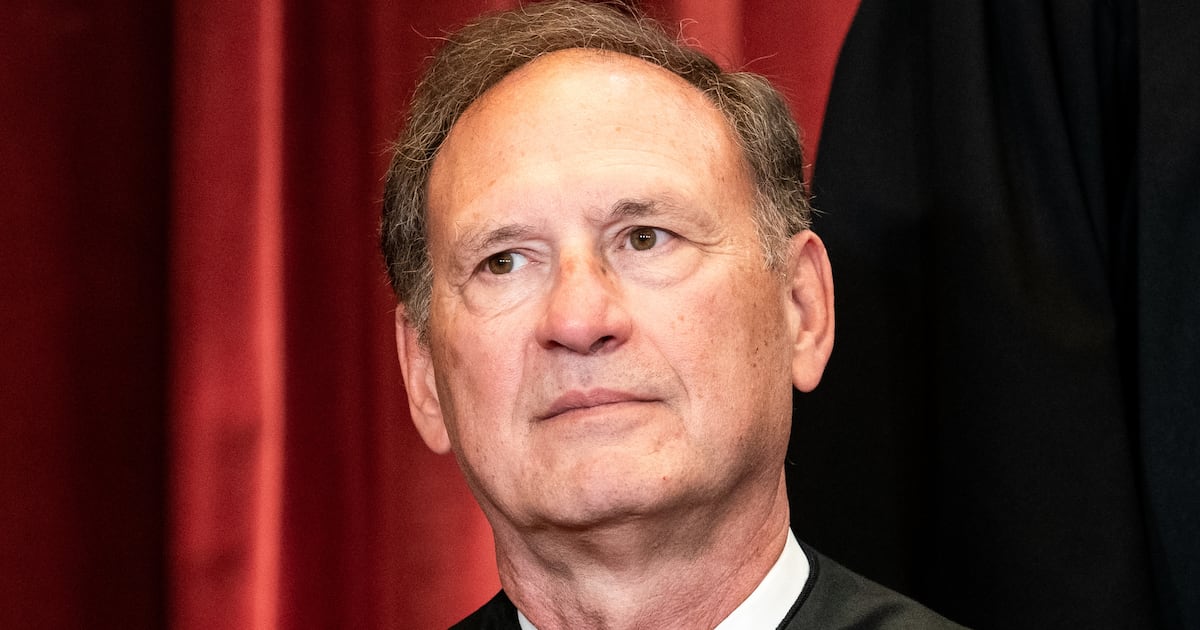

Sunday night’s new series arrives on Showtime with unusual pre-premiere interest. Philip Seymour Hoffman had actually played the lead in a pilot that was ordered to series, but the project was put on hold following the actor’s sudden death.

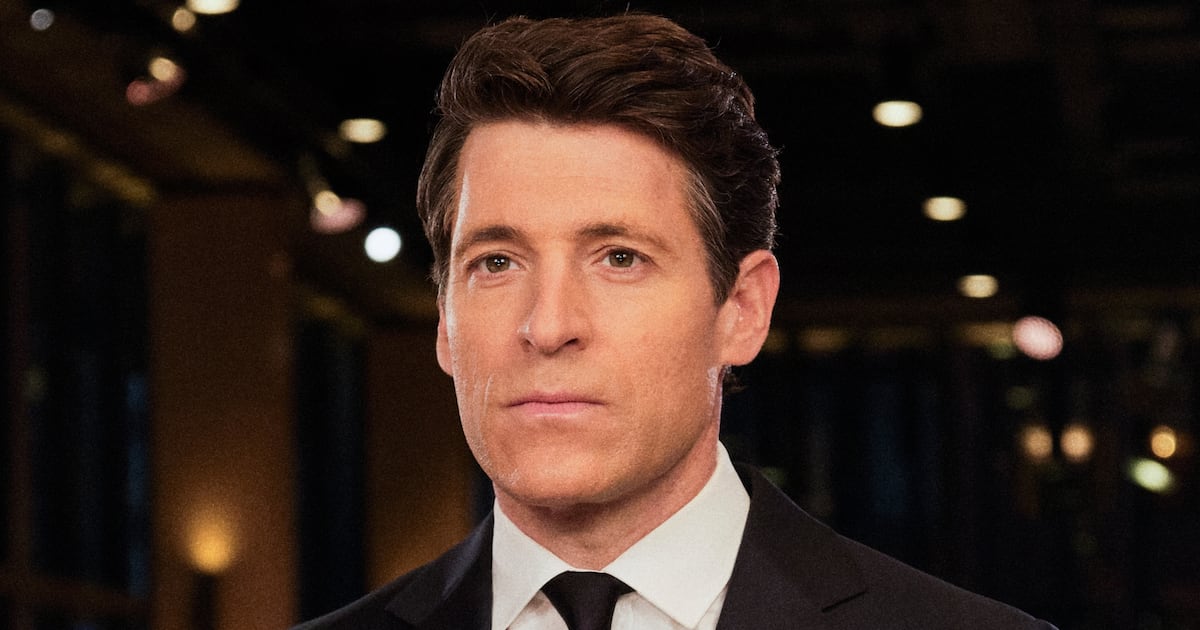

Last October, Coogan signed on to replace Hoffman. It was a hard decision to take over Hoffman’s role, and something that many of his friends cautioned him against doing, as Hoffman’s ghost would undoubtedly haunt his performance. “But if anything, the very fact that he’d been associated with it was a testament to the quality of the material,” Coogan tells The Daily Beast.

Once Coogan signed on, HAPPYish writer and creator Shalom Auslander retooled the part of Thom Payne to tailor it more to the Brit’s singular gifts.

His Thom would be an angsty-angry ad man whose world is disrupted when a 25-year-old wunderkind is installed as the new head of his agency, bringing with him a whole new lexicon: words like “viral” and “social” and “digital.” Thom encounters a surrealist midlife crisis—making out with and/or murdering Keebler elves are involved—as he, his friends, and family talk through his roadblocks to happiness.

The existential dialogue hits its most provocative peak during a conversation with a headhunter played by Ellen Barkin, when he suggests he might be happier at a new job. “That’s a myth, Thom. You’re as happy now as you’re ever going to be,” she says. “We each have our own joy ceiling. It doesn’t matter how much fucking money you have or how perfect your family or how many Pulitzers you win. You hit your joy ceiling, you’re done.”

“Joy ceiling.” It’s either the most enlightened or most cynical—the most accessible or the headiest—idea to hit television this year. As such, HAPPYish, with its absurdist fantasy sequences and dialogue-by-way-of-therapy, is also proving to be one of the most polarizing series to hit television this year.

“If something is liked by everybody then I’m not really interested in doing that work,” Coogan tells the Beast. “I think polarizing is not necessarily a bad thing—as long as enough people like it to keep it alive.”It’s a directive that’s proved fruitful for Coogan thus far, propelling him to status of comedy icon in the U.K. thanks to his indelible character, Alan Partridge. And here in the U.S., he’s coming off two Academy Award nominations for Philomena, which he produced, co-wrote, and starred in.

Ahead of Sunday’s HAPPYish premiere, we talked to Coogan about stepping into Philip Seymour Hoffman’s prodigious shoes, giving the fuck you to Thomas Jefferson, and why we may never be happy. (Though he very much seems to be. Ish.)

This must be a really interesting press tour because I imagine you’re not just being questioned about your role, but also someone else who played it before you.

It’s obviously something that’s going to come up. It’s part of the history of the show now, I guess. If time goes on and there are more seasons of the show, then it becomes more of a footnote, although an important one, in the genesis of the show. But had Philip Seymour Hoffman done an entire season it would’ve been an entirely different scenario. I wouldn’t have stepped into the role. Because he had only done a pilot that wasn’t broadcast and I felt that I’d have an opportunity to own that role and make it work for me.

Did you ever see the pilot Philip shot?

I didn’t. Deliberately so, because I didn’t want to have anything in my head. I will see it now that I’ve completed the season out of curiosity. And I think that was wise, from my point of view.

The pilot starts off with a big rant, the refrain of which is the phrase, “Fuck you, Thomas Jefferson.” It certainly makes an impression. How do you feel about that opening monologue?

It’s a good starter to set the tone for the show, which is a kind of anger and, also, the idea that it’s going to take a swing at sacred cows. It swings at the things that are supposed to be above criticism. And not just those kind of people who are idolized, but also the last remaining taboo, which is corporate America. Shalom said to me that one of the last things we’re not allowed to really criticize is corporate America because it’s so powerful. So it’s nice to be able to mention real companies and real products, which we do every week, and do so without being intimidated. Showtime has been very good in backing us to the hilt and wanting us to have real balls.

There’s a line in this pilot that I feel like encapsulates a lot of the show’s ennui and also the biting tone. Thom is lamenting that his depression medication won’t allow to him achieve an erection and says, “That’s life, either happy and soft or miserable and hard.”

That’s the sound bite-y way of trying to encapsulate things. I guess one of the benefits of Thom working in an industry like advertising is he knows how to reduce everything to bite-sized chunks. It’s also one of the reasons he hates the industry he works in. You can get audiences to think about stuff, if it’s good, that they wouldn’t normally think about.

There’s a lot of existential dialogue for them to respond to.

Particularly how the people of my generation feel lost in the new, constantly evolving world of social media. How do they relate to it? That generational gap that is emerging. I sometimes feel like I’m the last of the analog world. There’s a perennial struggle not just with middle age and trying to find out what happiness is, but with that whole thing of should you try to get up to speed and plugged into every new development in the digital revolution or should you say, “Hang it,” and I’m just going to be who I am.

Where do you sit on that spectrum?

Personally, I think if you try and not relate to it at all you’ll actually end up as the crazy guy living in a stone cabin in the hills. You have to embrace it. What I do is try to embrace as much as I need to do what I do, but I don’t want to become preoccupied with it. People are queuing up around the block because of some new Apple product. That, I think, is just insanity. It’s like the thing that’s supposed to help you express yourself becomes the thing you’re living your life for. There’s something science fiction-y about it that freaks me out. Of course, anything that can help us communicate is a good thing. You can’t be negative about the whole thing because it democratizes knowledge and empowers people. That’s a good thing. It’s good and bad. You gotta try to harness what you believe is positive about and try to kick back against what you think is unhealthy.

There’s a scene that skewers advertising’s role in this. But how did we become a culture that’s obsessed with happiness even though, as Ellen Barkin’s character says, we all have a joy ceiling that we’re never going to get through?

If people were not this obsessed with being content then capitalism would begin to fail. Because the notion is that you have to think that happiness is one consumer product away. Otherwise people will stop buying stuff that they don’t need. The whole Western civilization and capitalistic economy is built on people buying stuff they don’t need. That’s what’s touched on in this show. Advertising is a great vehicle for that.

How does the fact that Thom works in advertising affect his own pursuit of happiness?

Thom has an intellect and he’s creative. And he’s entered this pact where his creativity is being used not to enlighten the world or shed light on humanity. He’s using it to sell shit. That’s a big ethical problem for him. That’s something I can identify with. Personally, although I understand Thom’s angst, I don’t have that issue because I feel like I’m lucky that I’m able to put my creativity into stuff like this that talks about stuff and has substance rather than someone who’s just selling Coca-Cola, which I would find soul-destroying.

How does Thom justify it then?

You have to put food on the table, but he finds it mind-numbing. He works in advertising and admits that he’s sold his soul. But there are people who work in it and are prostitutes for corporate America and it doesn’t bother them in the slightest. Some people might think he’s a hypocrite, but he thinks that “As long as I’m bothered by this it means I still have a soul. The moment I buy into this lock, stock, and barrel is the moment I’ve entered the pact with the devil and crossed over to the dark side.”

The whole idea of the joy ceiling: I can’t decide if it’s the most enlightened thing I’ve heard, or the most cynical.

It’s interesting you see that. I say Shalom’s words—and they’re his words—but there’s sometimes a bleakness to his outlook that I don’t actually fully share. As a person I empathize a lot with Thom’s views, but I’m not totally in concert with them. If it’s a Venn diagram, it’s an 80 percent overlap between us. I think I have a slightly brighter outlook. But you’re right, sometimes it’s a little bleak. But that’s the tone of the piece.

Reading some of the profiles that have been written about you, there seems to be an obsession about your iconic status in Britain but not in America. Is it as much of a concern for you as for these writers?

Not at all. It’s something I have no control over. To me, all I try to do is work that I think is interesting and good. But always stuff that I do on my own terms. If that crosses over, then great. If not, it doesn’t matter. Because it’s not like I could do anything differently. So I just have to be honest and do work I believe in, and that will either translate or it won’t.

How does your fame in America compare to your fame in the U.K.?

Do I get recognized in America? No. I get recognized in Whole Foods by some hipster. And that’s OK! I don’t get recognized in Wal-Mart. But I’m doing the kind of stuff I want to do. In some ways, fame empowers you. But it can also be a handicap because people start to have preconceptions about you. An actual fact, because I’m famous in Britain, those preconceptions limit me. And because I’m not as famous in America, I can sort of do whatever I like because I’m not trying to get over some notion of what I am. It’s fine, in a way.