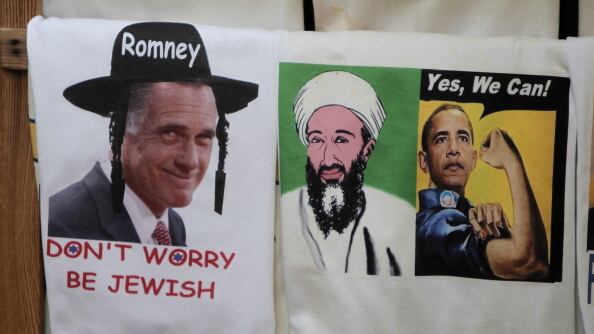

J Street and the Republican Jewish Coalition are out with exit polls about the 2012 Jewish vote. And they show, basically, that the pursuit of the 2012 Jewish vote is more interesting than the Jewish vote itself. Let me explain.

According to J St, President Obama won 70 percent of the Jewish vote nationally. The RJC says Obama got roughly 61 percent nationally, but in its poll more than six percent of respondents refused to answer. How big a drop this is from 2008 depends on what you believe Obama’s number was in 2008. The figure usually quoted is 78 percent. A more in-depth recent analysis suggests it was 74 percent. If the 74 percent figure is correct, Obama’s decline among Jews resembles his four point drop among white Americans as a whole. If the 78 percent figure is correct, the drop among Jews was a bit greater.

But even if Obama’s support among Jews did drop a bit more than among other Americans, the favored Republican (and often media) narrative that it is because he was too tough on Israel is almost certainly wrong. The J Street poll, like every other poll I’ve ever seen on the subject, found that only a small minority of American Jews vote on Israel. According to J Street, only ten percent of American Jews named Israel as one of their top two voting issues. (Another two percent mentioned Iran). The RJC asked a much cruder question, since it contained no comparative element: “In making your decision on whom to vote for president, how important were issues concerning Israel.” And even here, two-thirds of respondents chose “not” or “somewhat” important rather than “very important.”

The surveys contain other clues about the vast discrepancy between the political importance that the media thinks American Jews place on Israel and the political importance they actually do place on it. For instance, J Street found that only 69 percent of American Jews had never been to Israel. Almost twenty percent could not identify Benjamin Netanyahu. And while American Jews offered a generally positive appraisal of Netanyahu, they also overwhelmingly backed a Palestinian state near the 1967 lines with a capital in East Jerusalem, no Israeli troop presence on Palestinian soil, and even some limited return of Palestinian refugees—positions with which Netanyahu emphatically disagrees. By large margins, American Jews also favored Obama’s policies towards Israel and Iran over Romney’s, even though Romney tailored his views more closely to Netanyahu’s. There’s only one way to interpret these findings: Most American Jews just don’t follow this stuff that closely. They like Obama because he’s a liberal Democrat. They like Netanyahu because he’s the prime minister of Israel, and they don’t know, or think, that much about the policy disputes between them.

So if Obama’s numbers did drop slightly more among Jews than among Americans as a whole, what’s the reason? First, Sarah Palin wasn’t on the ticket. Non-Orthodox Jews have a neuralgic relationship to the Christian right, partly because American Jews associate (somewhat unfairly) right-wing American Christianity with the history of right-wing Christian anti-Semitism, and partly because non-Orthodox Jews are so secular that they line up on the opposite side of the Christian right on issues like abortion and gay marriage. The Republican Party’s fortunes among Jews, therefore, closely track the ascendance of the Christian right. The RJC is boasting that Romney’s 30 percent exceeds any GOP presidential candidate in the last two decades. What they don’t say is that every Republican candidate of the 1970s and 1980s save Gerald Ford in 1976 exceeded Romney’s share of the Jewish vote. Why? Because in the 1970s and 1980s, the Republican Party was less associated with the Christian right. Palin drove up Obama’s Jewish vote because she instantly became a symbol of the hard-line conservative Christianity that secular Jews fear. Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan, by contrast, despite their own quite hard-line views on abortion, were defined far more by their economic views.

The second reason that Obama’s Jewish vote may have gone down slightly is money. According to its head, David A. Harris, the National Jewish Democratic Council spent in the low seven figures—perhaps one or two million dollars—this year courting Jews. Another Democratic media operation, the “Hub,” spent $400,000. By contrast, the Republican Jewish Coalition spent $6.5 million. But an RJC board member told the investigative website Open Secrets that the real number was more like $15 million.

In a sense, the vast sums devoted to turning the Jewish vote Republican are more interesting than the Jewish vote itself. In recent decades, the Jewish vote has remained largely static. (No Republican has gotten 40 percent since 1956; none has won it since 1924). But during that same time frame, the role of Jews in the GOP elite has changed dramatically. In the 1970s, WASPs still so dominated the GOP’s operative and donor classes that few Jews felt culturally at home there. Henry Kissinger, for instance, though incredibly powerful himself, tried to limit the presence of other Jews in the Nixon White House because he feared triggering Nixon’s anti-Semitic tendencies, which he himself routinely endured. By the Bush era, by contrast, Jack Abramoff had opened a power-lunch kosher deli near Capitol Hill where all the TVs were turned to Fox. Bill Kristol is far more integrated into the GOP’s power structure than his neoconservative father Irving ever was. And today the GOP’s most famous big donor, Sheldon Adelson, is a Jew.

Just as other historically WASP-dominated elites have opened to Jews, so has the elite of the GOP. And Jews like Adelson have flooded in because the same income inequality that has so divided America in recent decades has divided American Jewry. The J St poll finds that while Obama beat Romney by 39 points among Jews who made under $50,000 a year, he won them by only 24 points among Jews who made over $100,000. And even that only hints at the real discrepancy because to understand the huge rise in Jewish money flowing into the GOP you’d have to poll those Jews making above $1 million a year. In that demographic, I suspect, Romney probably manages a tie. Would those Jewish millionaires say they’re backing Romney because of his views on Israel rather than his views on taxes? In a sense, it doesn’t really matter because the two are so deeply intertwined.

The real Jewish story of election 2012, in other words, isn’t about demand; it’s about supply. The demand to shift party allegiance among the mass of American Jews hasn’t really changed. What’s changed is the supply of Republican Jewish money trying to gin up some demand. In truth, Republican Jewish donors would probably be better off spending their money trying to influence constituencies more pliable than their own. But for many of them, I suspect, supporting a group like the RJC is personally meaningful. They’re not just trying to elect Romney. They’re trying to save their co-religionists from themselves. For most American Jews, voting Democratic is an expression of Jewish identity. For a small group of Jewish one percenters, by contrast, trying to keep other Jews from voting Democratic is an expression of Jewish identity. Culturally, it’s kind of interesting. In foreign policy, it may also matter, as Romney’s Adelson-driven Israel-pandering suggests. Electorally, until the GOP divorces the Christian right, it will matter virtually not at all.