With Donald Trump’s penchant for doling out so many presidential pardons to his uniquely troublesome circle of friends on his way out of the White House, it was only a matter of time until those presidential pals tested the value of their Get Out of Jail Free cards.

A case in Washington, D.C., is now highlighting the consequences of Trump’s messy pardons—and calling into question whether mercy handed out as a political favor has a limited shelf life.

“It’s not an exoneration exactly. It’s not like wiping a crime off the books entirely. It’s very valuable—as long as you don’t get in trouble again,” said David Levine, a professor at the University of California College of the Law San Francisco.

On Monday, a federal appellate court in the nation’s capital heard from Jesse Benton, a GOP political operative who is in knots over the fact that a jury heard about his previous election crimes—before convicting him of brand new ones.

The problem, as his attorneys see it, is that Trump’s pardon in 2020 should have made his first scheme essentially vanish. Instead, it revealed him to be what he is: a man who keeps getting caught playing dirty politics.

A three-judge appellate panel is now considering how to handle this kind of cognitive dissonance. Their decision could hinge on the manner in which the Trump administration quickly pumped out these pardons, circumventing an established review by the Justice Department that serves as a quality control.

American presidents have the authority to wield clemency as a means of unilaterally reversing convictions or even killing ongoing criminal cases. However, an established process tries to minimize the unscrupulous nature of this practice by routing this kind of reconsideration through a tiny corner of the Justice Department known as the Office of the Pardon Attorney.

However, the Trump administration largely ignored that.

“Presidents before Donald Trump had circumvented the pardon attorney. However, no prior president had made the evasion of this process the norm,” two university scholars noted in a 2021 study that found only 25 of his 238 pardons went through what is considered the proper channel.

In late 2022, an investigation by ABC found that at least 10 Trump pardon recipients had already fallen back into trouble just two years after the end of the Trump presidency—either by continuing misbehavior or loose ends from the initial investigations they initially faced. A letter from the White House cut short Kodak Black’s prison sentence for lying to the feds while trying to obtain a gun, but the South Florida rapper was soon caught with drugs. Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon dodged a federal trial for scamming xenophobic donors to the “We Build the Wall” campaign, only to face a mirror indictment from the Manhattan District Attorney.

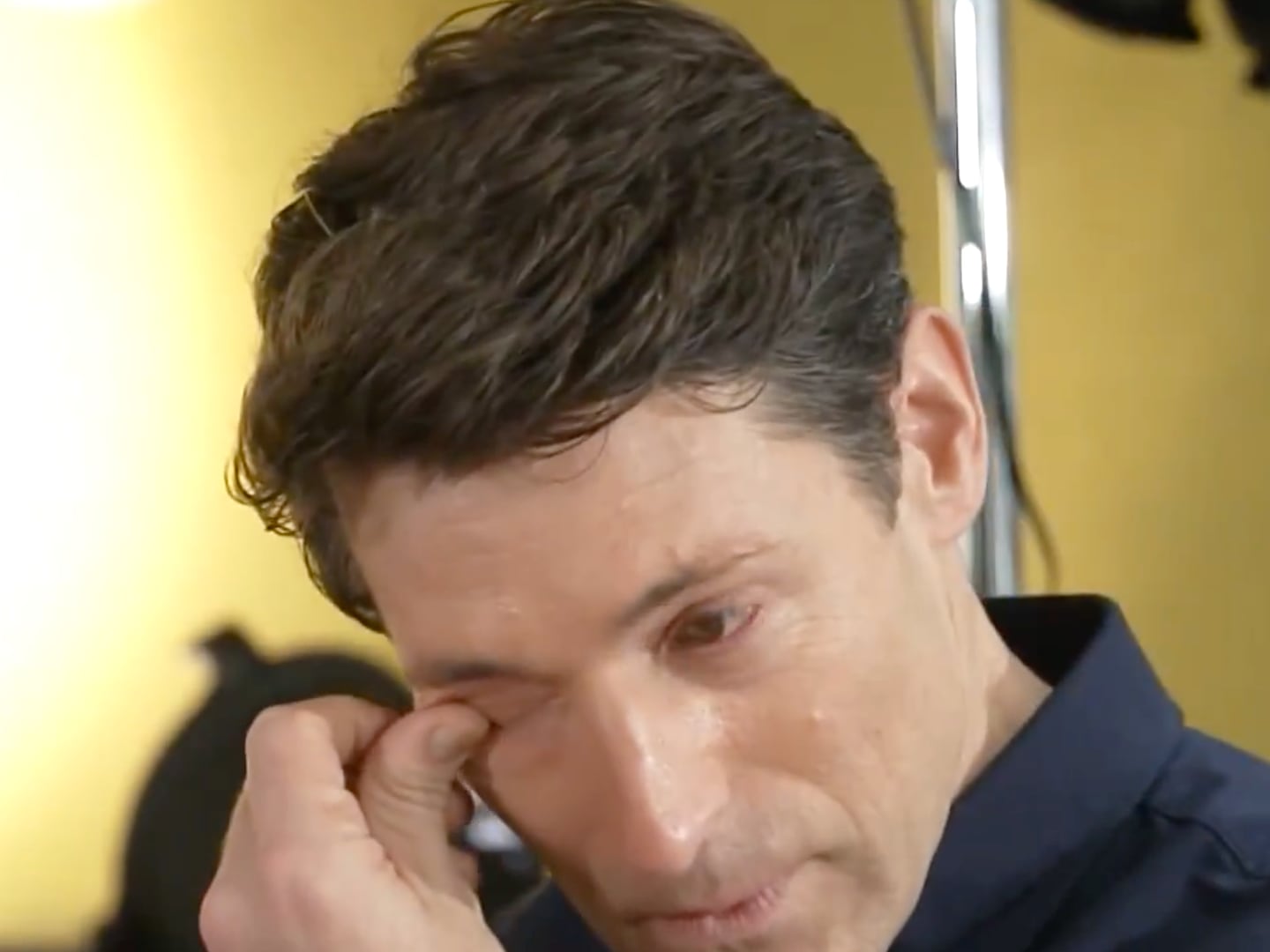

Levine, the California professor, pointed to what he considers a shoddy review process at the Trump White House.

“The pardon office has standards. They would explain why somebody was deserving of a pardon. They would have done a lot of homework and talked to the prosecutor in the case, and they would have the paperwork straight,” Levine said.

Former President Donald Trump speaks as he holds a campaign rally at Coastal Carolina University ahead of the South Carolina Republican presidential primary.

Sam Wolfe/ReutersInstead, Benton’s case forced prosecutors and his lawyers to give a close reading to a White House press release—one that lumped in 29 ex-cons, including the foreign cash-loving GOP adviser Paul Manafort, Trump’s daughter’s father-in-law Charles Kushner, and perhaps the slimiest conservative political operative of all time, Roger Stone. Released a day before Christmas Eve, the lengthy statement quoted a former Federal Elections Commission chairman reasoning that the law Benton broke “was unclear and not well established at the time.”

The trial judge thought the pardon was generic, not enough to wipe the slate clean. The Department of Justice recently told the appeals court that the press release “said nothing about the president’s motivations.” Meanwhile, Benton’s lawyers claimed “the pardon thus represented the President’s conclusive determination that Mr. Benton was innocent because he lacked fair notice and did not willfully violate the law.”

“That’s just a bad reading. The press release does not support that claim. Any court would recognize it,” University of Michigan law school professor Richard Primus told The Daily Beast.

The innocence question is an important one. Pardons declaring someone innocent totally nullify a conviction, so that previous case can’t be used against them at some later trial. There’s no criminal history, because history is rewritten. But that’s a difficult argument to make for Benton.

While working on Ron Paul’s longshot presidential campaign in 2011, Benton bribed an Iowa politician with $73,000 to switch his endorsement to the libertarian underdog just days before the state’s influential primary caucuses. But just four months after Benton got convicted in 2016, he orchestrated a $100,000 deal that funneled money from Russian businessman Roman Vasilenko, who wanted to take a picture with Trump, to the MAGA candidate’s presidential campaign. Benton then tried to clean up the scheme by laundering the money through his own funds.

The most experienced of the three judges at Monday’s appellate hearing, Judge Karen LeCraft Henderson, zeroed in on the proceeds of the crime.

“The amount of money was $100,000. And Mr. Benton gave the Republican Party, whatever the committee was, $25,000. Whatever happened to the $75,000?” she asked.

“I don’t know exactly what happened with that money. It's possible that he kept it or he did something else,” said Benton’s lawyer, Nick Harper.

Benton’s case hinges on the appellate court’s interpretation of how his trial employed federal rule 404—which ironically has nearly the opposite meaning of the computer network code by the same name that pops up every time a file is missing. The federal rule allows prosecutors to use prior convictions to prove a person’s identity. It’s akin to recognizing a master thief by his distinctive break-in techniques.

“It’s evidence showing that the person who did it this time is probably the person who did it the prior time, because that’s the way he works,” said Mark Osler, who runs the Federal Commutations Clinic at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota

Which is why Judge Bradley N. Garcia on Monday noted that “there is a definitive ruling that the [pardoned] conviction can come in for willfulness and mens rea” (a person’s criminal state of mind) because it “shows a certain M.O.”

The legal question for this appellate court is whether it was fair for the jury to hear about Benton’s Iowa bribery before convicting him of the Russian photo op scheme. After all, the jurors were specifically told to decide only on the second case and instructed to narrowly consider the previous one. They were told “you may not use this evidence to conclude that he has a bad character or that Mr. Benton has a criminal personality.” Federal court rules fiercely protect a person deemed innocent, but they give prosecutors more leeway if a pardon falls short of that.

Simply put, a pardon doesn’t make it all go away.

“It’s more nuanced than that. It relieves the person of many of the effects of the conviction. But it doesn’t erase the past,” Osler explained.

Benton’s ongoing legal battle in D.C. is a harbinger of what’s to come for the dozen or so others who have cases working their way through courts across the country. Their pasts may, indeed, come back to haunt them at the end of their newer trials.

Presidential pardons aren’t new to this federal appellate court. Henderson herself was on the panel that unanimously refused to free White House aide Scooter Libby in 2007 when he appealed his convictions for his role in outing CIA officer Valerie Plame—only to have President George W. Bush immediately commute his sentence hours later.

More to the point, however, Henderson has already wrestled with the mess that vague, last-minute pardons leave in their wake.

Given her 34-year tenure, she was there when the entire circuit was reviewing a case—only to be interrupted when President Bill Clinton, days before Christmas 2000, suddenly pardoned a Tyson Foods executive who got caught schmoozing the Agriculture Department secretary with a free flight to supposedly derail food safety regulations. The D.C. appellate court wouldn’t let it go without a few parting shots.

“Certainly, a pardon does not, standing alone, render [Archibald] Schaffer innocent,” the court noted. “In fact, acceptance of a pardon may imply a confession of guilt.”

They determined that the bland wording of Clinton’s signed executive grant of clemency merely acted on the conviction “without purporting to address Schaffer’s innocence or guilt.” And that’s exactly where many of Trump’s pardons now stand.

The flood of press releases about presidential pardons that Trump hastily issued in his final days at the Oval Office—while he was simultaneously busy plotting to remain in power after losing the election—were lengthy. But the vast majority make no mention of a person’s actual innocence.

“Historically, presidents haven’t had any requirement that they explain why,” Osler said. “That’s why these Trump press releases are kind of remarkable—they’re much more than we usually got. They’d do batches of pardons, list each one, and often would give a reason why.”

But, like Trump, they now appear to be all show and little substance.