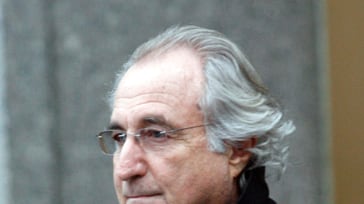

Like the mythic vampire, a Ponzi scheme needs to find new blood to sustain itself. So while Bernard L. Madoff had no problem creating the illusion of constantly expanding profits through the simple device of wholly inventing the transactions in accounts he managed, the only way he could meet requests for redemptions was to find new money. The amounts he needed became staggering in the 1990s, as a handful of his longtime associates cashed in billions of dollars of imaginary profits in their accounts.

His feeder funds fared well, earning hundreds of millions of dollars in fees from their 20 percent cut of Madoff’s imaginary profits and their equally imaginary “performance.”

To replace these billions, Madoff needed a new source. The mother lode he turned to was the ganglia of so-called feeder funds.

A feeder fund, unlike a hedge or private-equity fund, does not manage investments. It is simply a marketing operation. Its principals raise money from investors—often through their social, country club, and professional connections—that they then consolidate into a single account, which they funnel to a money manager with whom they have an arrangement.

Typically, in return for finding investors for the money manager, the feeder gets a relatively small placement fee of about 1 percent. The money manager then charges for his investing skills, typically deducts a performance fee of 20 percent from the profits as well as an annual “net asset” fee of 2 percent on the investor’s nest egg.

But Madoff offered feeder funds a much more alluring deal for finding him money. Instead of merely giving them the standard placement fee, he allowed them to take the entire cut of profits usually reserved for the money manager by waiving all his fees. This generous accommodation became extremely lucrative for them because Madoff reported profit annually of about 15 percent. So the principal of the feeder could deduct 20 percent of that putative profit from all their clients’ accounts, transfer it to their own “carry” account, and redeem it, with the result that they got cash while their clients’ fictitious profits grew each year.

But why would a highly successful money manager like Madoff make such an accommodation and essentially work for free for feeders? The explanation Madoff gave was that he was not greedy and content making a mere .04 cents a share from trading stocks in the accounts (which he could have made anyhow if he charged them a fee). As incredible as this rationale might sound, feeders had little incentive to look a gift horse in the mouth. This amazing inducement, together with the track record Madoff had totally invented, brought in enough from feeder funds to more than cover the $8 billion in withdrawals made by his longtime associates.

For their part, his feeder funds fared well, earning hundreds of millions of dollars in fees from their 20 percent cut of Madoff’s imaginary profits and their equally imaginary “performance.”

Consider, for example, the success of Fairfield Sentry, a unit of the Fairfield Greenwich Group, whose principals included the socially prominent financier Walter Noel Jr., his four well-connected sons-in-law, and Jeffrey Tucker, a former Securities & Exchange Commission official. According to the complaint filed by Irving Picard, the court-appointed trustee for the liquidation of Madoff’s business, between December 1, 1995, and 2008, “it invested approximately $4.5 billion with Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities through 242 separate transfers via check and wire.”

From its cut of Madoff’s notional profits, the Fairfield Greenwich Group “reaped massive fees, in excess of hundreds of millions of dollars, purportedly for investment performance which has proven to be nothing but fiction.”

The Wall Street Journal, which reviewed Fairfield Greenwich’s own records, reported that the firm earned $160 million in the fees it garnered from the money it outsourced to Madoff in 2007 alone. Before the Ponzi scheme collapsed in 2008, the trustee alleges that Fairfield Greenwich, and the entities under its control, withdrew more than $3.5 billion from Madoff. Presumably part of those redemptions included its own fees. Fairfield Greenwich denies it engaged in any wrongdoing and insists that it informed its investors of its relation to Madoff.

But some feeder funds failed to disclose their cozy relationship with Madoff, according to complaints filed by authorities in New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Consider, for example, the charges files against the entities of investment guru Ezra Merkin, who sits on the board of and invests for a number of universities and charities. Merkin’s three funds had (at least on paper) some $2.4 billion invested with Madoff, according to the 54-page civil complaint filed by New York State Attorney General Andrew Coumo.

Cuomo alleges that Merkin collected hundreds of millions of dollars of performance and net asset fees based on the fictional transactions of Madoff while he “actively obscured” that Madoff, not he, was managing money. Merkin’s three funds, called Ascot, Ariel, and Gabriel, all had money with Madoff. Ascot was purely a feeder fund for Madoff, whereas Gabriel and Ariel, which were supposed to perform complex arbitrages on distressed debt, divided their money between Madoff and two other money managers.

“The incentive fee Merkin collected included 20 percent of the profits reported by Madoff, which, of course, were fictitious,” the complaint notes. “Even after subtracting expenses and fees paid to other outside managers, Merkin’s fees for Ariel and Gabriel totaled more than $280 million.”

Meanwhile, Ascot produced an additional $169 million in net asset fees. And, according to the complaint, these fees were paid directly to Merkin, who did not reinvest them with Madoff via the feeder fund. While collecting these fees, Cuomo alleges, “Merkin’s deceit, recklessness, and breaches of fiduciary duty have resulted in the loss of approximately $2.4 billion” to his investors.

Merkin denies any wrongdoing. In the court papers filed on July 1, 2009, he asserts that his dealings with Madoff were known to his investors and there was no deceit or breach of his duty. Perhaps so, but if Cuomo’s assessment of Merkin’s financial records is accurate, Merkin raked in nearly $450 million in fees by giving Madoff the lion’s share of his investors’ money.

Madoff may have provided even more extraordinary emoluments to some other of his feeders. Consider, for example, what the trustee describes as “The Curious Case of Sonja Kohn.” Kohn met Madoff in the mid-1980s, when she had her own brokerage company in New York. She then founded the Bank Medici AG in Vienna and used it as a feeder fund for Madoff.

Raising money from the newly rich oligarchs of Russia and Eastern Europe, she eventually placed (on paper, at least) an estimated $3.5 billion with Madoff. After the collapse, the trustee sorted through the records of one of Madoff’s front companies and found that sizable transfers had been made to Kohn, even though she did not work for that company.

Next, as The Wall Street Journal reported, prosecutors in the U.S., Britain, and Austria launched their own investigations of alleged payments she received from Madoff. According to the affidavit filed by U.S. prosecutors in Vienna, some $32 million was paid by Madoff over a course of 10 years to a New York company that was “owned by Sonja Kohn personally,” while, according to a similar British affidavit, $11.5 million was paid by Madoff’s London subsidiary to another company she allegedly controlled.

If such payments were indeed made by Madoff, they provide an additional inducement for money-raisers to feed Madoff’s insatiable Ponzi scheme. Kohn states through her spokeswoman that neither she nor the Bank Medici received any kickbacks from Madoff and describes herself as “the greatest Madoff victim.”

Even excluding such alleged side payments, Madoff’s feeders extracted more than $1 billion in performance and net asset fees from his phantom profits. While there is no evidence in any of the litigation that indicates that any of these feeders were privy to Madoff’s grand Ponzi scheme, they had intriguing clues that might have cast their golden goose in a different light, such as Madoff’s inexplicable generosity in relinquishing his entire performance fee just to get his hands on their money, his curious practice of exiting the market entirely at the very end of each quarter so that his quarterly statements to the feeder funds would list nothing but Treasury bills and cash, and, even curiouser, his employment of an unknown two-man accounting firm in New York's Rockland County—operating out of a 13-by-18 office, no less—to audit all his multibillion-dollar operations.

Missing such flashing signs that something was amiss while they harvested their rich bounty of fees may be understandable on Wall Street but, in my book, it hardly qualifies them for victimhood.

Edward Jay Epstein studied government at Cornell and Harvard, and received a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1973. The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood is his 13th book. The sequel, The Hollywood Economist will be published in January 2010.