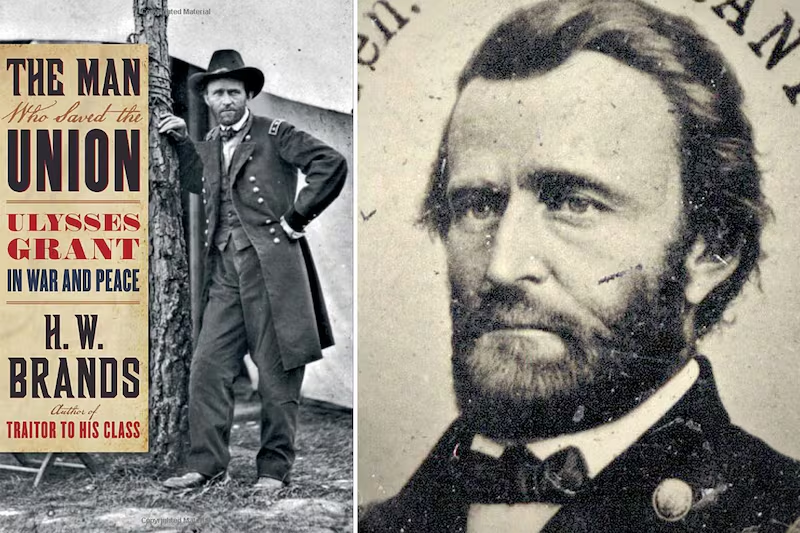

About once a decade it becomes necessary to remind Americans again that Ulysses S. Grant was a great man, indeed a giant figure. The usual way to try to do this is by publishing a thumping big biography, and let me say that there is nothing wrong with this, although it still hasn’t worked. There is nothing new to learn about Grant, no titillating secret (unlike, say, Thomas Jefferson and his relationship with Sally Hemings), no hitherto unpublished letters or diaries—indeed, all Grant biographies tell pretty much the same story. He remains the man on the face of the $50 bill, portrayed in a strikingly unflattering and amateurish engraving that gives him the appearance of a middle-aged man with a grizzled beard and a bad hangover, which is appropriate enough, since the one thing that most Americans know about Grant is that he had a problem with alcohol. The 31 massive volumes of Grant’s letters and papers (each volume almost the weight of a Civil War cannonball) are still available, though one doubts many people buy them, and it is typical of Grant’s decline in history that the Ulysses S. Grant Association has migrated from Ohio, where he was born, to the University of Southern Illinois and finally to Mississippi State University (of all places), where his papers now reside, deep in what used to be the Confederacy. Grant might have had a faint, mournful, ironic chuckle over this.

Grant’s tomb, in Riverside Park, New York City, a small slice of greenery begrimed by the fog of exhaust smoke, at West 122nd Street, sandwiched between Riverside Drive and the busy West Side Drive, remains sadly shabby and surrounded by a ridiculous, ugly, and wildly inappropriate freeform sculptured wall, a hideous, modern local community structure that looks as if it had been clumsily sculpted in a local kindergarten out of shiny red Play-Doh. That his tomb is there in the first place is typical of Grant’s poor judgment about matters off the battlefield. If it had been placed in Washington, it would be a gleaming national tourist attraction, perhaps placed close to the Lincoln or the Jefferson memorial, where he belongs, but the president and Mrs. Grant did not care for Washington, D.C. Galena, Ill., was eager to have Grant’s tomb, but the Grants did not think Galena was the right place to bury America’s most successful general and did not look back with pleasure on the years during which Grant, having resigned from the Army and failed at several professions, worked as clerk in his father’s harness store in Galena wrapping parcels and was ridiculed as the town drunk. Grant rejected West Point, his alma mater, because regulations precluded Mrs. Grant from being buried beside him when her time came, and since Grant was never happy when separated from Julia (he did not drink when they were together), he was unwilling to be separated from her in death. They chose New York City instead, and with the mournful lack of judgment that afflicted Grant whenever real estate or money were concerned, they made the mistake of believing that the Upper West Side was the coming neighborhood and with its view over the Hudson was sure to be the most elegant part of the city, the equivalent of Paris’s 16eme arrondisement or London’s Belgravia, not imagining that they were consigning their remains to a part of New York that would become famous for gang warfare and drug dealing, where no sensible person goes out for a walk at night.

Yet until the First World War, Grant’s tomb was a bigger tourist attraction than the Statue of Liberty, it was built with $600,000—the largest sum ever raised for a memorial at the time—contributed by nearly 100,000 of Grant’s grateful fellow citizens, and more than a million people lined the streets to see his body carried there, in a procession of more than 60,000 mourners, including President Grover Cleveland, two ex-presidents, the justices of the United States Supreme Court, and countless generals, including two of the Confederate generals he had defeated, Joseph E. Johnston and Simon Bolivar Buckner.

When magazines publish lists of the best or worst presidents, Grant is always likely to fall into the latter category, despite that as president he prevented America from going to war with Britain or France, treated Native Americans with a decency and sympathy never emulated by his successors, did more than his share to bring the former Confederate states back into the Union as political equals, and appointed the first black to West Point as a cadet.

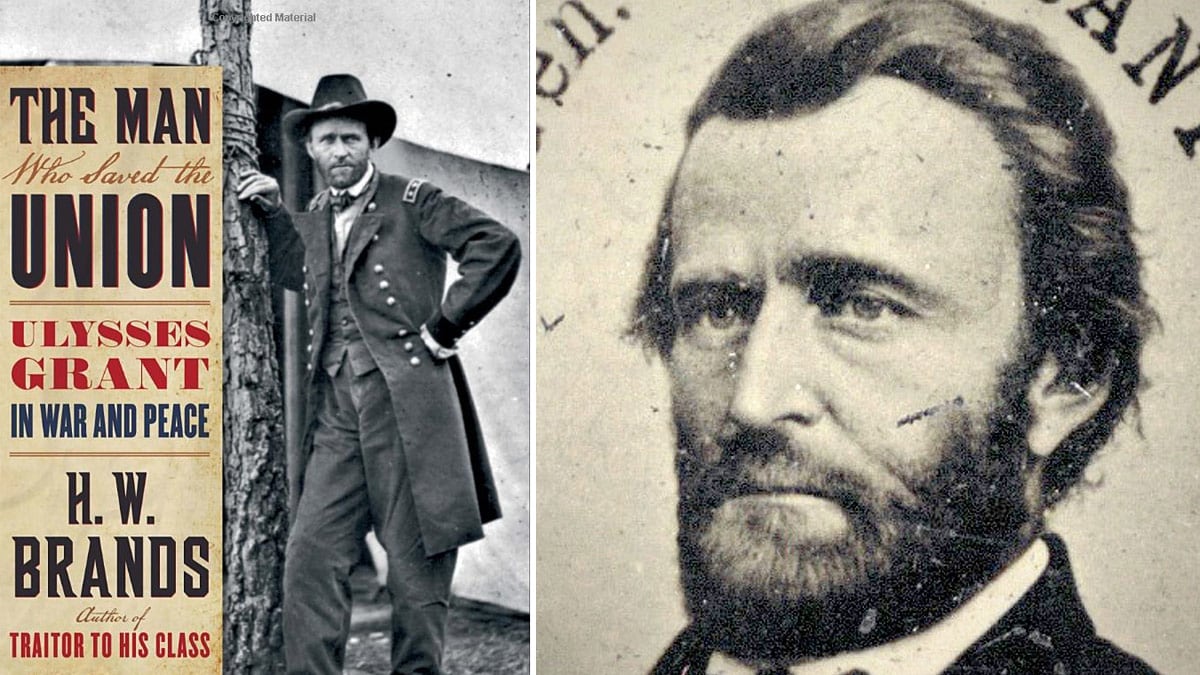

What is more, Grant was at once a Horatio Alger success story and, as Professor Brands points out, “the man who saved the Union,” as well as the best general America has ever produced and the author of what is arguably one of the twin bedrocks of American literature, Moby-Dick in fiction, Grant’s Memoirs in nonfiction. There was a time, at any rate north of the Mason-Dixon line, when even in the poorest household you would find two books, The King James Bible and Grant’s Memoirs—the latter perhaps the greatest nonfiction bestseller of the 19th century after the former, and the spare, chiseled, direct prose of which, never a word too much or wasted, was admired by everyone, and served as the inspiration for such American writers as Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein.

Professor Brand’s biography of the victor of Vicksburg is thorough, balanced, and a good read, although, it must be said, he skimps on Grant’s childhood, which is a pity, particularly since Grant himself commented on the art of biography, “I read but few lives of great men because biographers do not, as a rule, tell enough about the formative period of life. What I want to know is what a man did as a boy.” I am afraid Grant would, in this respect, be disappointed by Brands’s book, since he only gives Grant’s childhood and “formative years” four pages out of 637. Four pages from the arrival of the Grants in America in the 1630s to the arrival of Grant in West Point seems be just the reverse of what Grant would have wanted in a biography, but never mind, Brands isn’t writing for Grant. After that, his book tells Grant’s story in a very readable and respectful way, though like most of Grant’s biographers he finds the General’s meteoric rise during the Civil War from retired captain to the first lieutenant general since George Washington and commander of all the Union armies more interesting than the two terms of Grant’s presidency, or the disappointing years that followed his departure from the White House, a national hero second only to Washington, an international celebrity, and a complete failure at handling his own or other people’s money, not from dishonesty, for Grant was scrupulously honest, but because he was as naive as a baby about financial matters, as his publisher Mark Twain commented, and not very much less so about choosing his friends, the members of his cabinet, and his business associates.

William S. McFeely’s Grant remains the gold standard where biographies of Grant are concerned, a work of literature as well as a biography, but once Brands gets to the Civil War, his narrative, like his subject, marches to a faster pace, and Grant’s story, though it has been told before, is told well, and gives a believable impression of the man himself, who despite his shyness, his dislike of giving speeches, however short, and his unprepossessing appearance—it is typical of Grant that when he accepted Robert E. Lee’s surrender of the Army of Virginia at Appomattox Court House he was, through no fault of his own, clad in a wrinkled and muddy uniform and without a sword, whereas Lee wore a brand-new uniform, polished boots, a gold sash, and an elaborate sword—was a man of extraordinary energy, patience, fairness, and battlefield genius, with a dry wit and a very American dislike of what would now be called “big shots,” or who thought themselves better than he was.

Apart from his victory at Vicksburg, which together with Gettysburg, fought at the same date, sealed the fate of the Confederacy, Grant’s finest and noblest moment was his negotiation with Lee and the supreme tact and patience with which he brought the Civil War to an end. As the two men parted, Lee remounting Traveller to ride back to what remained of his army and assume his role as the warrior, saint, and martyr of the Lost Cause, Grant standing on the porch of the McLean house, the Union gunners began to fire a hundred gun salute. Grant ordered them to stop. “The Confederates are not our prisoners,” he said. “We do not want to exult over their downfall.” He may or may not have said, “We are all Americans again now,” but it is certainly what he thought. Like Grant himself, Brands moves on from that epic moment—perhaps the epic moment—of American history, with a certain reluctance. Lee moved on to become myth, but Grant was only 43, he had a whole life in front of him, and nothing, not even the presidency, could compare with that moment, watching a gray-bearded man, in a gray uniform, on a gray horse ride away as every Union officer present lifted his cap in respect. Grant had won the Civil War. The story from his birth to that moment is a heroic saga, the story from then to his death from cancer, a long tragedy, but Brands tells both parts well, and fairly, and deserves great praise for once more attempting to put Ulysses S. Grant where he belongs, in the pantheon of American heroes.