Once again we are in Montana, in the “two-saloon town” of Gros Ventre, for Ivan Doig’s 11th novel, The Bartender’s Tale. And once again we are in the past, this time on the cusp of the 1960s. English Creek flows nearby, as it does through most of Doig’s novels, his second even going by that title. The rugged, rural expanse of the West serves as a backdrop to a steadily unfolding family drama.

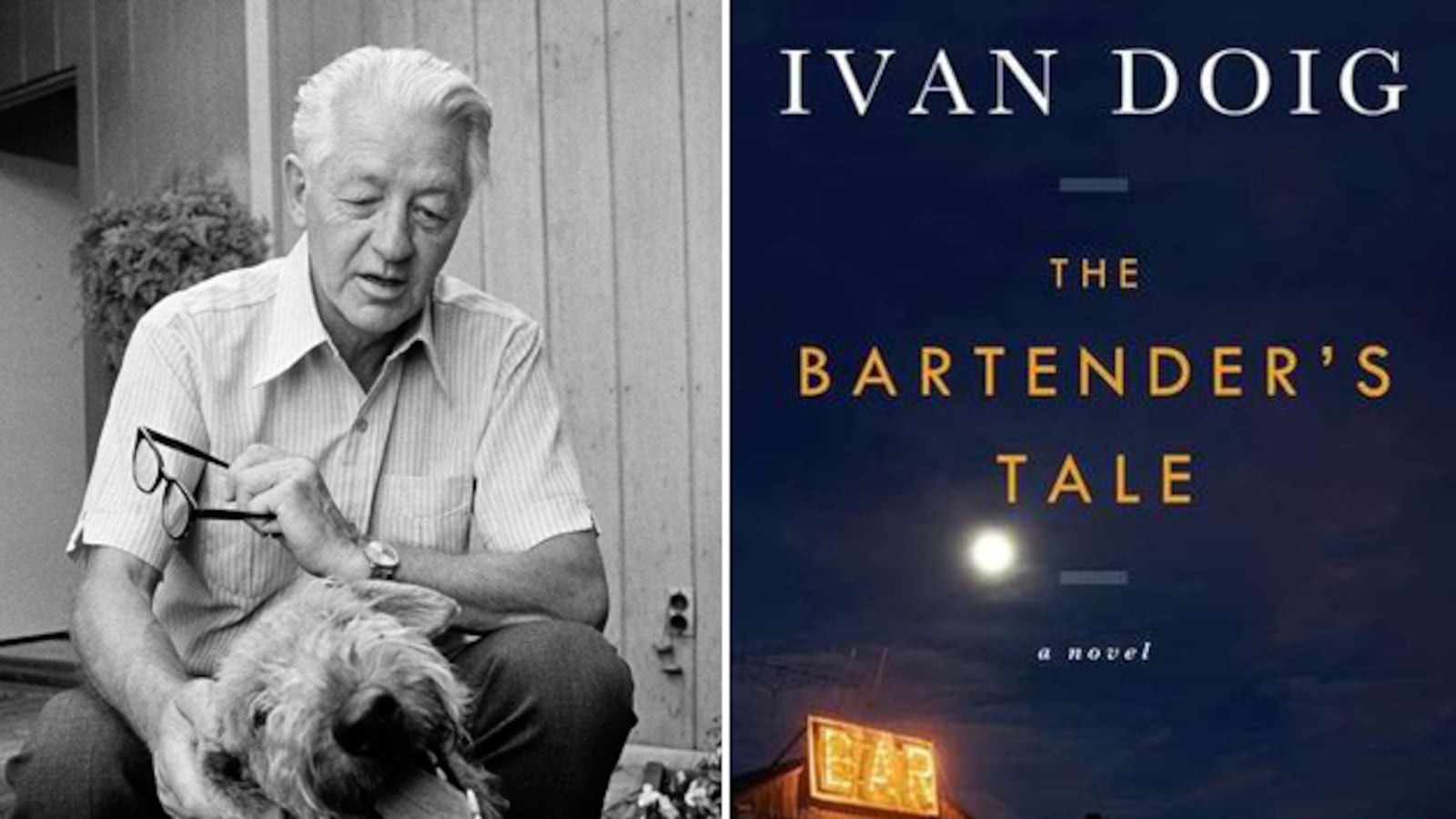

Doig has been dubbed the successor to Wallace Stegner as the Dean of Western Writers, and with this expert novel, in which he sets himself a larger canvas and fills it with a diverse cast, he bears out the Stegner comparison. He evokes an end of an era and dramatizes the power of the past—standard themes of the American landscape novel. His characters’ back stories are revealed to expose their at times duplicitous cores, as we witness Doig’s most autobiographical novel to date, with a fictionalized rendering of some of the father-son escapades we encountered in his 1978 memoir This House of Sky: Landscapes of a Western Mind. Fact and fiction are skillfully fused to document a boy’s last days of youth and a history his father can’t leave behind.

At the heart of the novel is the strongly drawn father-son pair: Rusty, our narrator, and Tom, his father, who is apparently the best bartender who ever lived. After an unhappy early childhood spent with his aunt in Phoenix, Rusty, “an accident between the sheets”, is rescued by Tom and whisked back to Montana. Rusty, at the age of 12, becomes a “half-pint participant” in his father’s bar. Once the watering-hole of homesteaders and cowboys, the Medicine Lodge now caters to ranchers, roughnecks and day-tripping tourists, with a back room stuffed with things left behind by drinkers who can’t afford to pay their bar bills. Rusty loses himself in loot, this “King Tut’s tomb of the prairie.” He enrolls in a fishing derby and meets his nemesis Duane Zane, who doesn’t “take up much alphabet.” He falls in love with a girl named Zoe, who “seemed to come from that foreign end of the alphabet.”

Rusty’s youthful adventures are enchanting, but Doig does something more—he punctuates them with the colorful local idiom of his father’s grizzled punters. Along comes Del, an oral historian, who wants to track down and interview Tom’s former drinking clientele at the Mudjacks Reunion in Fort Peck. Doig uses Del, a “collector of Missing Voices” who catalogs old stories and local dialects with a van full of recording equipment called “the Gab Lab”, to explore his interest in surveying the “pure lingua America” that still blossoms in the West. We may be as baffled as Rusty by grizzled punters who pepper their speech with “bobbasheely” (a good friend, actually a Gulf Coast slang), “honyocker” (a failed homestead farmer) and “turster” (a drunk who destroys toasters), but we can join Del in gleefully soaking it all up.

Rounding out the cast of characters are Proxy, a “milk-blond force of nature” and a supposed stand-in for Marilyn Monroe who is Tom’s old flame, and Francine, her erstwhile wild-child daughter, who turns out to also be the daughter Tom never knew he had. The last part of the novel focuses on the awkward reunion of this “slapped-together family,” and Rusty’s fear that the irrepressible Proxy could in fact be his mother.

Rusty describes his father as someone who “would not tell the least tale about anything,” who only “pours the drinks for the lost dreamers, eternally swabbing the bar while listening to their stories, ever listening.” Like father, like son: Rusty sits at a vent in the back room of the bar as a clandestine “earwitness,” absorbing the town gossip. Zoe likes this about him: “Priests do this all the time … People come and tell their troubles, and they get to feel better because somebody is listening to them.” Doig has written a novel about listening and recounting. As Proxy and Francine’s arrival twists neat family ties into a tangled skein, it becomes clear that Tom does indeed have a tale to tell, and a mesmerizing one at that. A father might not be able to leave his past behind, but by revealing it he’s freeing his son and releasing him into the future.

Stegner, in an introduction to Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs: Living and Writing in the West, his collection of essays on the American West, argued that “the remaining western wilderness is the geography of hope.” Stegner’s writing sought to track and capture the West’s vast and varied landscapes, its diverse history and culture, but also its indigenous optimism. “The West,” he wrote, “is hope’s native home.” A new generation of writers, he believed, was continuing this tradition. Doig’s was the first name Stegner mentioned. In these writers Stegner could feel “the surge of the inextinguishable western hope. It is a civilization they are building, a history they are compiling, a way of looking at the world and humanity’s place in it. I think they will do it.”