The most arresting idea in Adam Winkler's impressively learned study of US gun law, Gunfight, is the suggestion that contemporary American gun culture was more or less invented by the Black Panthers.

Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the party founders, had studied law and discovered California allowed the carrying in public of loaded rifles and shotguns, provided that the guns were not pointed at anyone. They seized on this law to stage theatrical confrontations with an Oakland police force they deemed hostile and oppressive - and then, most dramatically, in May 1967, to walk armed into the chamber of the California State Assembly. Police tried to intervene, but Newton and Seale recited the authorizing law, and pushed ahead.

The Newton-Seale stunt - and the outrage and surprise it deliberately elicited - was made possible by America's pre-1960s gun culture. Pre-1960s Americans lived comfortably both with guns and with substantial gun regulation. Nineteenth century Americans banned concealed weapons. Often they forbade firearms altogether within the limits of a city. Twentieth century Americans outlawed categories of weapons associated with criminal activity: Tommy guns, for example, in the National Firearms Act of 1934.

In two world wars and then the Cold War draft army, the government had compelled millions of American men to carry a rifle in that government's defense. For those veterans - as for the Union Army veterans who had founded the National Rifle Association in the 1870s to better train soldiers for future wars - the rifle symbolized the connection between the people and the people's government.

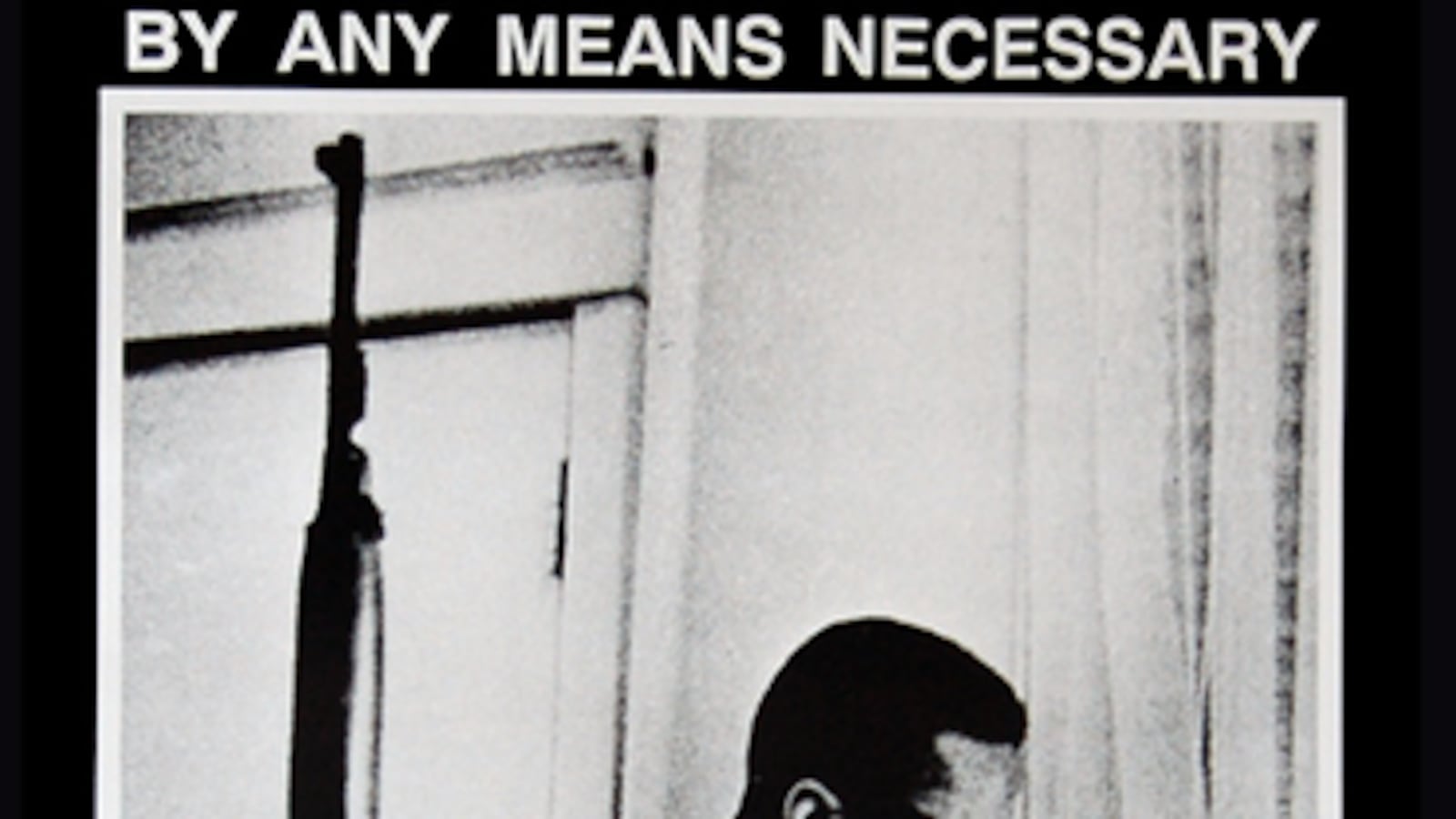

Newton and Seale thought different. They regarded government - the white man's government - as the oppressor and the police - the white man's police - as the enemy. They carried their arms against the government and against the police. The gun symbolized and guaranteed their rights. And the gun they most valued was not the policeman's revolver, not the sportsman's shotgun, but the military style weapon with its distinctive extended magazine. The iconic photograph of Malcolm X with an M1 carbine, taken in 1964, carried the message (although Malcolm X had of course nothing to do with the Panthers).

Flash forward half a century. Every one of those old Black Panther themes has been absorbed and redeployed by modern gun rights militants. Hostile government? Check. Self-defense against police or other law enforcement authorities? Check. Military style weapons as symbols of freedom? Check and check.

There had been previous cases where Americans organized themselves into anti-governmental paramilitary forces. But in the past, these forces recognized themselves as illegal: that's why the Ku Klux Klan of the late 1860s wore hoods. The Klan never pretended it was exercising a constitutional right.

What was different about the Black Panthers, at least at the start, was the pains they took to organize their militia movement within the law.

Here's a marvelous description from Gunfight:

In February of 1967, Oakland police officers stopped a car carrying Newton, Seale, and several other Panthers with rifles and handguns. When one officer asked to see one of the guns, Newton refused. “I don’t have to give you anything but my identification, name, and address,” he insisted. This, too, he had learned in law school.

“Who in the hell do you think you are?” an officer responded.

“Who in the hell do you think you are?,” Newton replied indignantly. He told the officer that he and his friends had a legal right to have their firearms.

Newton got out of the car, still holding his rifle.

“What are you going to do with that gun?” asked one of the stunned policemen.

“What are you going to do with your gun?,” Newton replied.

By this time, the scene had drawn a crowd of onlookers. An officer told the bystanders to move on, but Newton shouted at them to stay. California law, he yelled, gave civilians a right to observe a police officer making an arrest, so long as they didn’t interfere. Newton played it up for the crowd. In a loud voice, he told the police officers, “If you try to shoot at me or if you try to take this gun, I’m going to shoot back at you, swine.” Although normally a black man with Newton’s attitude would quickly find himself handcuffed in the back of a police car, enough people had gathered on the street to discourage the officers from doing anything rash. Because they hadn’t committed any crime, the Panthers were allowed to go on their way.

The people who’d witnessed the scene were dumbstruck. Not even Bobby Seale could believe it. Right then, he said, he knew that Newton was the “baddest motherfucker in the world.” Newton’s message was clear: “The gun is where it’s at and about and in.”

It's an oddly contemporary scene, isn't it? Only today, the armed person challenging the power of the police is much less likely to be a young black radical, and much more likely to be an older white conservative.

"The gun is the only thing that will free us," declared the Panthers.

"The purpose of having citizens armed with paramilitary weapons is to allow them to engage in paramilitary actions. " That sentence is quoted not from the Black Panther manifesto, but from an article published just a few weeks ago in National Review by Kevin Williamson.

Before 1965, it would have occurred to precisely nobody that the Second Amendment guaranteed the right to organize private armies independent of the state. People often describe the Second Amendment as ambiguous, but the Americans of the 1790s knew exactly what a militia was. As the federal Militia Act of 1792 enacts in its very first section, a militia was a military force organized by a state government and subject to that government's authority. In times of emergency, the militia could be summoned by the president and be subjected instead to national authority. A group of persons, however well armed, who resisted the government were not a "militia."

They were, in the words of the second section of the 1792 act, "combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings …" In April 1861, Abraham Lincoln would repeat precisely that language in his first proclamation calling forth the militias of the northern states to suppress the rebellion in the South. Meanwhile, the Southern militias in turn rallied to the call of the government they regarded as legitimate, first that of their state, then that of the Confederacy. The Confederacy never allowed Southerners the right to rebel against their own government. It denied, rather, that the government in Washington DC was "its own." That issue was tested and settled 150 years ago.

Since then, dissident groups have from time to time resorted to armed force against local or national authorities. But these groups, however passionately they believed in their cause, never imagined themselves to be acting lawfully. That's why the Ku Klux Klan wore hoods, rather than uniforms: they recognized the risk that if identified they would be arrested and prosecuted. They did atrocious things, but they never pretended to a right to do them.

What was new about the Black Panthers was their attempt to organize an armed militia within the law. Although the group did later degenerate into a criminal gang, its early success was gained precisely from its ostentatious compliance with law. As one former Panther would later write, "The sheer audacity of walking onto the California Senate floor with rifles, demanding that Black people have the right to bear arms and the right to self-defense, made me sit back and take a long look at them."

Remove the overt reference to race, and you have a sentence that could proceed from an NRA militant today.

Most Americans who own guns do so in hope of protecting themselves against criminals. (Hunting has dwindled into an increasingly marginal activity: only about 6% of Americans over age 16 have a valid hunting license.)

But in recent years, the ideology of the gun rights movement has put increasing emphasis on an idea very alien to most gun owners: armed resistance to authority. This armed resistance is usually represented as merely potential and hypothetical. Yet at the same time, it's also stressed that the hypothetical may not be so remote as all that.

When tyranny does arrive, these gun militants want to be ready. In their scenario, however, the target of governmental oppression will not be poor slum-dwellers, but the property-owning and God-fearing. Yet the struggle is the same, and so (the theory holds) the NRA must stand now where Bobby Seale and Huey Newton stood before, only with this one difference: white will be the new black.

- MORE TO COME -