Could there be any more desperate group of consumers than new moms? It’s a perpetual market, and one that is willing to spend: Everyone who’s pregnant, adopting, or raising little kids in America is in a constant state of craving—for medical information, strollers, toys—and, perhaps most of all, reassurance.

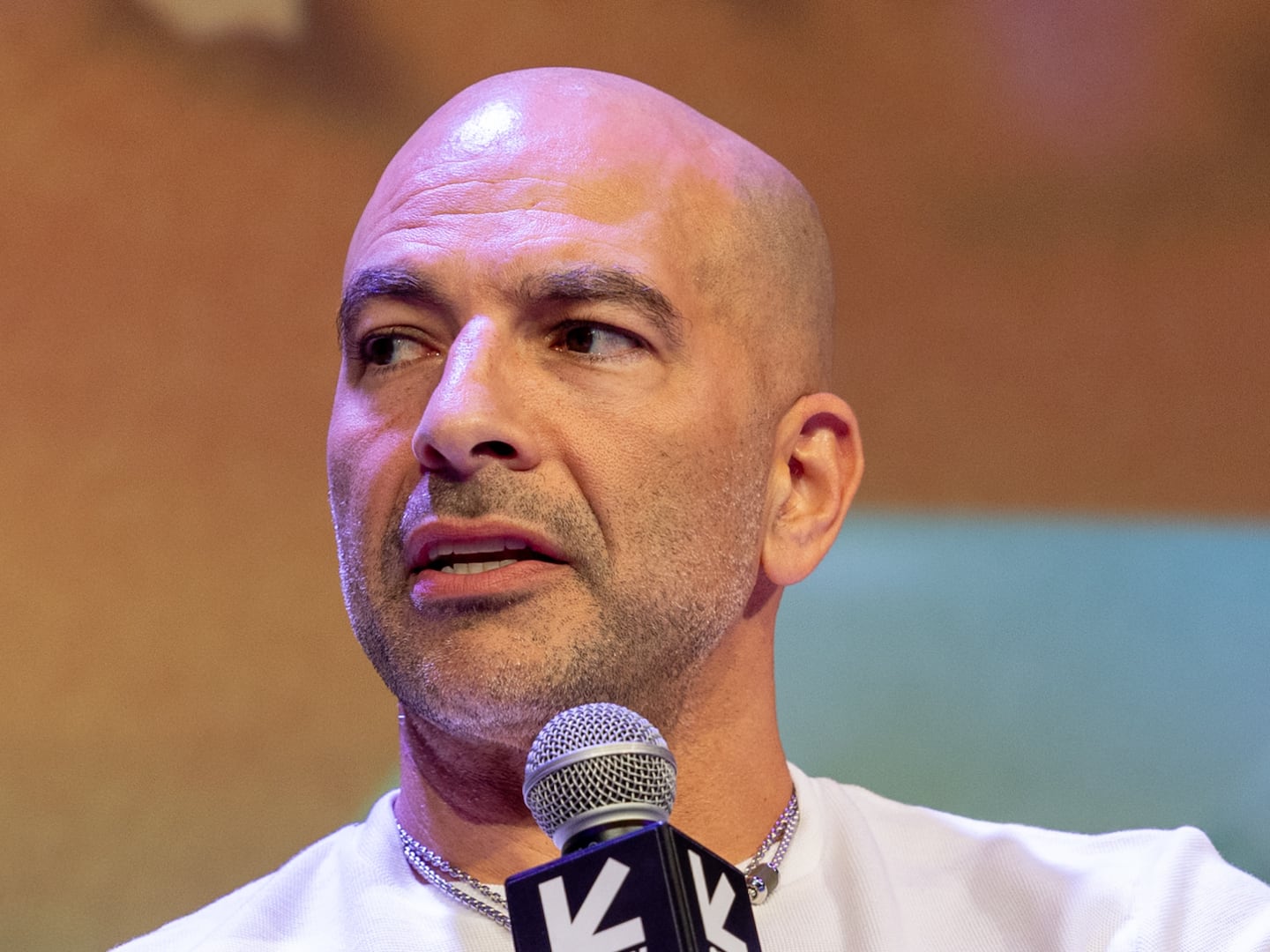

And Tina Sharkey, 45, is delivering it all to them at an amazing rate. Sharkey is president and CEO of BabyCenter.com, which reaches almost 80 percent of American households online that have offspring at any stage from in utero to age 8. If you think about it, that means that in some parts of the country, there’s not a single playgroup parent who isn’t logging on to BabyCenter at one time or another.

The site, as Sharkey sees it, isn’t just selling clicks; instead, she says, it offers companies insight into “tribes”—meaning people who have a commitment to a common purpose.

BabyCenter’s formula is simple: advice tailored to each mom’s family circumstances. Say you have a 4-year-old boy, a 2-year-old girl and another child expected in four months. After registering with the site, you’ll start getting its pregnancy bulletin, detailing what’s happening with your baby (at 24 weeks, she weighs about a pound, and her taste buds are developing), and you’ll be asked if you’re planning to breast-feed. If so, BabyCenter directs you to a “Top 10” list of nursing “essentials,” articles on breastfeeding basics (reviewed by BabyCenter’s medical advisory board), and links to BabyCenter nursing groups. You can also post pictures of your kids, vent about your terrible 2-year-old, and check out a video of a Caesarean section (warning: not for the faint-hearted).

The site, as Sharkey sees it, isn’t just selling clicks; instead, she says, it offers companies insight into “tribes,” meaning people who have a commitment to a common purpose—in BabyCenter’s case, raising children. As the individuals in these tribes act, react, and engage, they generate “egosystems.” An egosystem composed of “passion players,” she argues, is a valuable source of customer information.

OK, it’s perilously close to New Age jargon—Sharkey lives in Marin County, after all. But her point is that advertisers and sponsors pay a premium to connect with BabyCenter (she won’t say how much) because the site’s audience spends a lot of money and is intensely engaged with the product, i.e., their children. BabyCenter is not a retailer, though parents can buy everything they need (and a lot of stuff they probably don’t) via its marketing partners. There are 250 of these, covering everything from artificial nipples to real-estate and financial services.

Like many an Internet infant, BabyCenter was conceived by two young (and, at the time, childless) men; it launched in 1997. The founding fathers loved their brainchild dearly, but not so much as to turn down an adoption offer from eToys (remember them?) for $150 million. No surprise, the year was 1999. Two years later, eToys was bankrupt; in the ensuing tag sale, Johnson & Johnson bought BabyCenter for $10 million. BabyCenter is now one of the 200-plus standalone companies that make up the J&J empire, and it’s the only media company.

Earlier this year, BabyCenter shut down its online retail shop, opting to serve as a marketing and advertising platform for the likes of Target and diapers.com, rather than compete with them on their own turf. In 2007, Sharkey figured that BabyCenter was worth $500 million; she declines to offer a new estimate. Revenue was $73 million in 2006, according to The Deal, another figure Sharkey declines to update, only saying that growth is outpacing the industry. She won’t say whether the site is profitable.

Sharkey is intelligent, confident, and successful. Her teeth are perfect, her two sons, ages 10 and 7, are cute. Any normal person would itch to dislike her, but damn it, she is also charming and thoughtful. There is, however, a discernible vein of iron: The crowded Internet baby business is no place for cuddles. “She’s a fairly relentless tactitian and manager,” says Ted Leonsis, the former vice chairman of AOL, where Sharkey worked before joining BabyCenter.

No question. Sharkey can talk the tech talk fluently, and walk it, too. She spent the first year at BabyCenter overseeing the replacement of the creaky Web 1.0 infrastructure to improve social-networking capabilities, something she further enhanced with the acquisition of mayasmom.com. But she is much more interested in what the technology enables—what might be called the sociology of online business. And that insight has been crucial to her evolution into an online impresario of parenthood.

It's not an obvious place for a Manhattan-raised daughter of the rag trade to end up. For that, credit a power mom, the running man, a college course, and a giant turntable.

The power mother is Sharkey’s own, who went back to work when the youngest of her three daughters was in sixth grade, and eventually became president of Perry Ellis America. (Her father and grandfather were also in the garment industry.) “A superstar and a role model,” Sharkey says of her mother, who died last year.

The running man is the little yellow cartoon logo that AOL used for years. Sharkey associates it with Leonsis. “He taught me about empowering consumers and always putting them at the center of the experience,” Sharkey says. At AOL, she was in charge of “social media"—and takes credit for coining the term, a claim that is bolstered by her ownership of the domain name socialmedia.com.

The college course was at the University of Pennsylvania, where she did her thesis on Minitel, the French telecom service that began in the 1980s and in many ways anticipated the Internet. The course was on “group processes,” a subject that has intrigued her ever since: “The way that people come together and apart; who gets anointed as leader.”

And the turntable comes from the rotating stage at the shopping-network QVC, where Sharkey worked in the early 1990s. The stage was divided into quadrants; the camera would shoot one quadrant, while the other three would be set up for the next shot. The combination of technology and real-time interaction “was this inspired, crazy thing,” she says.

In 1995, Sharkey became one of the founders of iVillage, AOL’s effort to create a space on the Internet just for women. Visiting the Parent Soup chatroom late one night, she asked the assembled mothers what they liked most about it. The answer: each other. It was a lightbulb moment for Sharkey: “I knew at that moment that things were different. I was no longer a producer, but a facilitator.” Fourteen years later, Sharkey still sees herself that way.

What’s next? Expanding internationally; BabyCenter is now in 18 countries, using local editors and advisory boards. Enhancing connectivity. Developing higher-value services to sell. Sharkey’s goal is simple, and audacious: "We want to be the world’s partner in parenting."