I recognize that it's easier to criticize a battle plan from outside the combat zone. I also repeat that President Obama, his political advisers, and White House officials surely didn't instigate, direct, or countenance any IRS targeting of Tea Party or conservative groups. It would have been politically stupid, even suicidal—because it could have blown up in the midst of the 2012 campaign. And at the political level, Obama and his team have shown remarkable smarts since 2007—and as Mitt Romney could attest, a stunning capacity to survive and prevail. In the end, events and the evidence will lead to the overwhelming conclusion that IRS conduct in the Cincinnati field office is a quintessential incarnation of that portion of government that the science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein called "stupid fumbling."

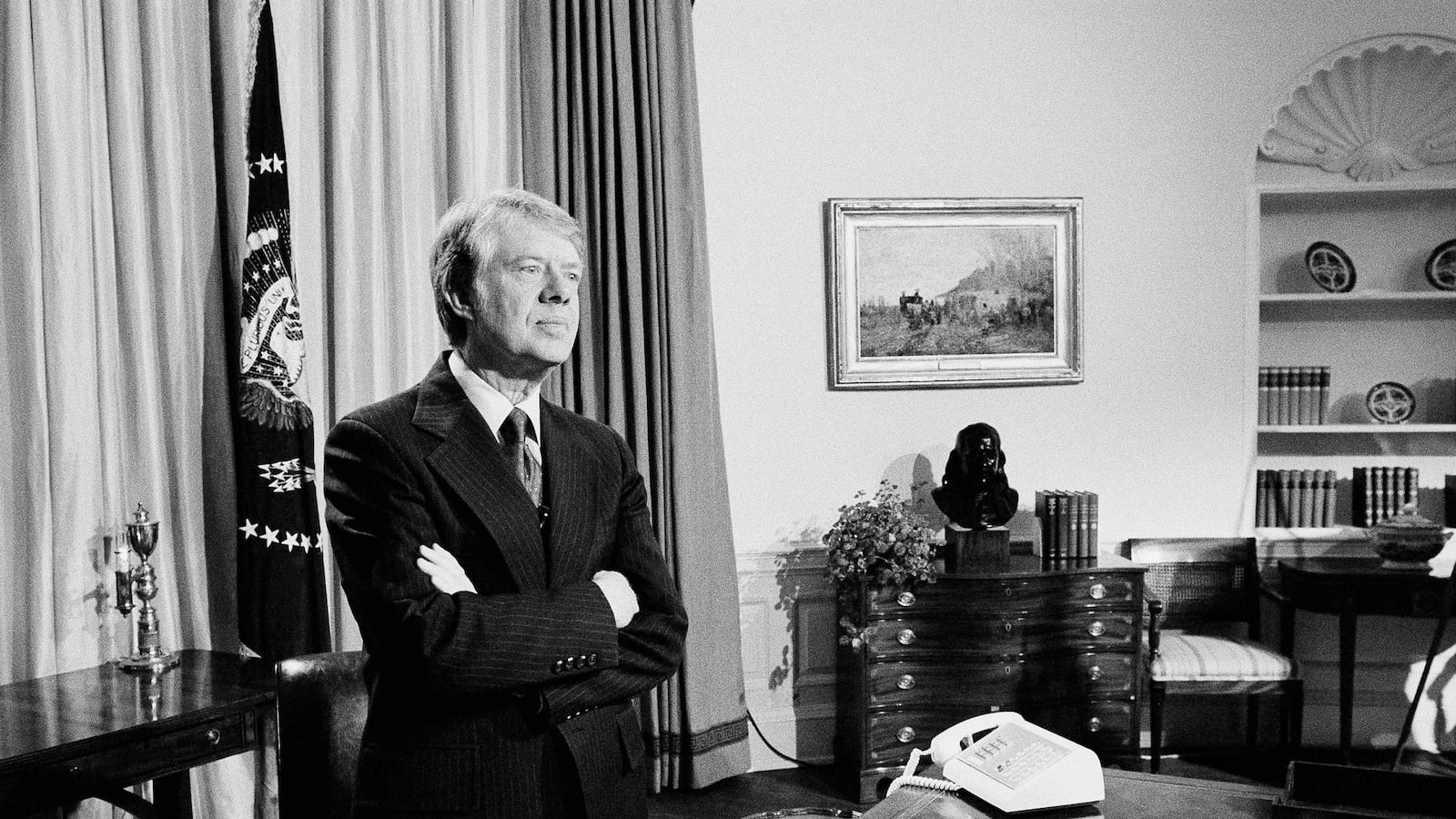

For the White House, there is no crime here, there is no scandal, no matter how feverishly, irresponsibly, or demagogically the GOP labors to concoct one. This is not a case of Nixonian indifference to the Constitution, the law, and the president's oath of office. But it does look like a reprise of Cartersque incompetence, increasingly so as we learn more about how the White House staff handled—or mishandled—a crisis they knew was coming.

White House Counsel Kathryn Ruemmler was told about the inspector general's pending IRS report on April 24. She didn't inform the president, supposedly to "shield" him. And at first, the White House claimed, she didn't tell anyone else either. That claim soon evaporated as the administration conceded that she had "briefed" Chief of Staff Dennis McDonough and other aides. Then the next shoe: other officials in the Counsel's office had known even sooner than Ruemmler. Then another: White House and Treasury staff had conferred about how to deal with the report.

House Speaker John Boehner's press secretary gleefully tweeted: "I can't wait until tomorrow's version of events." That says it all about a plainly hapless effort to protect the president—which instead seems likely to yield a prolonged inquisition into the interstices and tick tocks of what is now routinely referred to as a "scandal," distracting the White House and enthralling the Washington press corps day after day, and conceivably for months on end. GOP overreaching, as I've argued, may hurt the party in the 2014 midterms. But despite all the invocations of legal propriety—of not interfering with an ongoing investigation—it's hard to credibly contend that the White House strategy here, if you can even label it that, has been a model of crisis management.

White House Press Secretary Jay Carney has become a serial punching bag at the daily West Wing press briefings. He's been close to unflappable amid a storm of restatements, retractions, and inconsistencies. Nonetheless, he should never have been sent out there without being fully informed—and it's no excuse to suggest that all the facts weren't available or assembled yet. They were all known somewhere in the White House—or at the Treasury. The aides who had been briefed early on certainly hadn't forgotten that; they just forgot to tell Carney.

Yes, the Republicans yearn to make a mess of any kind at any time. Yes, the distinctions and revisions here may be irrelevant—and frequently petty. Still the story feeds ferociously on them—and thus the president's men and women have inadvertently, awkwardly given aid and comfort to his adversaries.

Was there a better way?

We don't know exactly what Ruemmler was told. The Washington Post has reported that it was "a thumbnail sketch … that the IRS had improperly targeted Tea Party and conservative groups." Presumably, that's what she passed on to other Obama staff. And that should have been enough to set off alarm bells—and set in motion a coherent planning process so the president could move decisively and thoroughly as soon as the headlines hit.

Did he have to be so conspicuously left out of the loop in his own White House? He could have said that he had been informed the report was coming, say two weeks before, but couldn't react or act until the news was out. But even if he was cosseted in darkness, those around him who had seen the unhappy light could have hammered out a contingency memo to put on his desk at a moment's notice. Then he could have responded quickly and more convincingly—which is what campaigns depend on, and what presidents have to do, when time is of the essence.

And you can't assume that everything will go according to schedule. So it's no excuse to plead that the story leaked early, at the ham-handed behest of Lois Lerner, the IRS official who would soon cite the Fifth Amendment and refuse to testify before a congressional committee. Lerner had planted a question, word for word, with a participant at a conference, which she answered by revealing what the IRS had done before the Inspector General could issue his report. Apparently, she was aiming to get herself ahead of the curve—she was in charge of the offending IRS unit—and provide some cover for the agency. The result was exactly the opposite. And the White House staff should have realized that the big story tends to leak.

If the president's advisers had gamed all this out—if he had been looped in or at a minimum prepared to adjust and swiftly execute the game plan—it's possible he could have taken command from the very start.

Saying at the outset that the White House or that he himself had been informed a couple weeks earlier actually could have given him an advantage. It would have made the decisive steps he could have announced immediately look like considered measures, not a rushed attempt to channel the news cycle.

Then, on that very first day, he could have and should have fired the acting commissioner of the IRS. (He did that later.) While it's impossible under the law to dismiss civil servants out of hand, he could have and should have said that anyone at the IRS involved in the targeting of right-leaning organizations would be put on leave. (Lerner the leaker has been. But what about the others? If they had contested any such decision, it would have strengthened the president's credibility. The White House shouldn't have let the lawyers stand in the way.) Obama could have and should have immediately announced a Justice Department investigation. (It was announced—a day later—by Attorney General Eric Holder, not the president.)

I have no doubt that the president's outrage was genuine—that he was deeply angry. But the harsh words he did speak needed to be backed up, on the spot, by tough deeds. This was a time for some drama, Obama—for a White House fully committed to engage the issue, get out everything that was known, and pursue every conceivable remedy. Instead the information and decisions have come in dribs and drabs, as redrafts and corrections, propelling wave after wave of IRS stories.

There are now Republicans demanding a special counsel. It won't happen, and shouldn't. For now, Americans believe the president is telling the truth—and in a CNN poll, 55 percent agree that "IRS employees ... were acting on their own." Still, that's muted consolation for a president and a White House already facing the challenge of developing a fresh strategy for a season of unprecedented gridlock.

As anyone who reads my columns knows, I regard Barack Obama as an exceptional president of high achievement. But on the IRS story, there was systematic "fumbling" in the West Wing. I agree with Obama's former press secretary Robert Gibbs that "it's the responsibility of people inside ... who know that they have information or knowledge to go to Jay [Carney] and make his job easier." Indeed, they needed to do a much better job all around as the crisis gathered. And they will have to do it again, not just in all the faux scandals that will relentlessly run their course, but in great political battles ahead.

On the IRS, the course probably will be longer than it had to be. For the White House, the problem here resembles Carter, not Nixon. It isn't about crime; it's about competence. This president didn't do anything wrong. But the West Wing sure didn't do everything right.