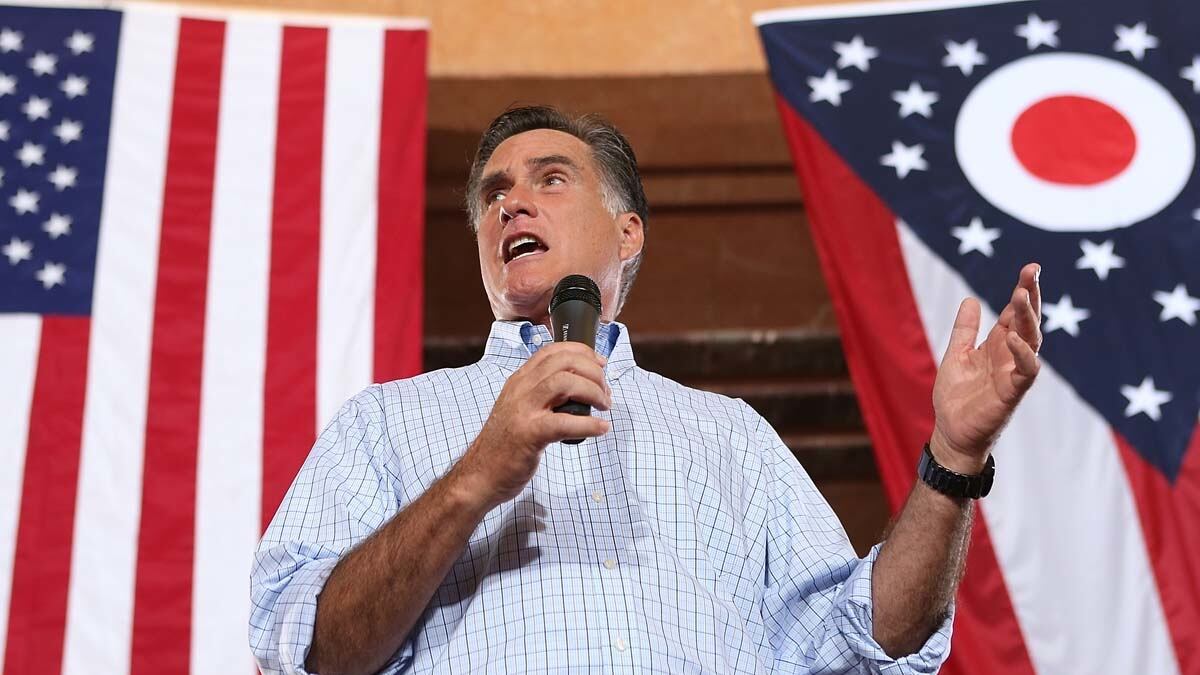

Mitt Romney is the most unpopular major-party presidential nominee in recent U.S. history.

As far as I can tell, there is simply no precedent for Romney’s sustained favorability slump.

Mitt Romney is the most unpopular major-party presidential nominee in recent U.S. history.

As far as I can tell, there is simply no precedent for Romney’s sustained favorability slump.