The presidential debates are iconic, high-profile events that attract global media attention. So why are only a relative handful of American colleges vying to host them?

Most of those that wind up with the honor are hardly household names. On Monday, President Obama and Mitt Romney will face off for the third and final time at Lynn University in Boca Raton, Fla.

Initially, dozens of schools express interest, says Mike McCurry, co-chairman of the Commission on Presidential Debates. But many are scared away by the cost and commitment required.

“They learn that you have to load up on your power, bring in new air conditioning, pay for a lot of security. The financial commitment the school makes is a minimum of $1.5 million,” McCurry says, which goes to the commission for production fees. “At that point a lot of schools opt out of the process.”

Only 12 schools applied to host this year’s presidential and vice-presidential debates.

Of that dozen, Hofstra University on Long Island was picked for the second time. The total cost to the school: $4.5 million.

“We had the perfect facilities, but we still had to do a tremendous amount of work,” says Stuart Rabinowitz, the university’s president. “We had the basketball arena, but we had to turn it into a television studio according to exact specifications, and we had to bring in fiber-optic cable. There’s a tremendous amount of infrastructure work that’s done, and it literally takes months, and then security has to be put up.”

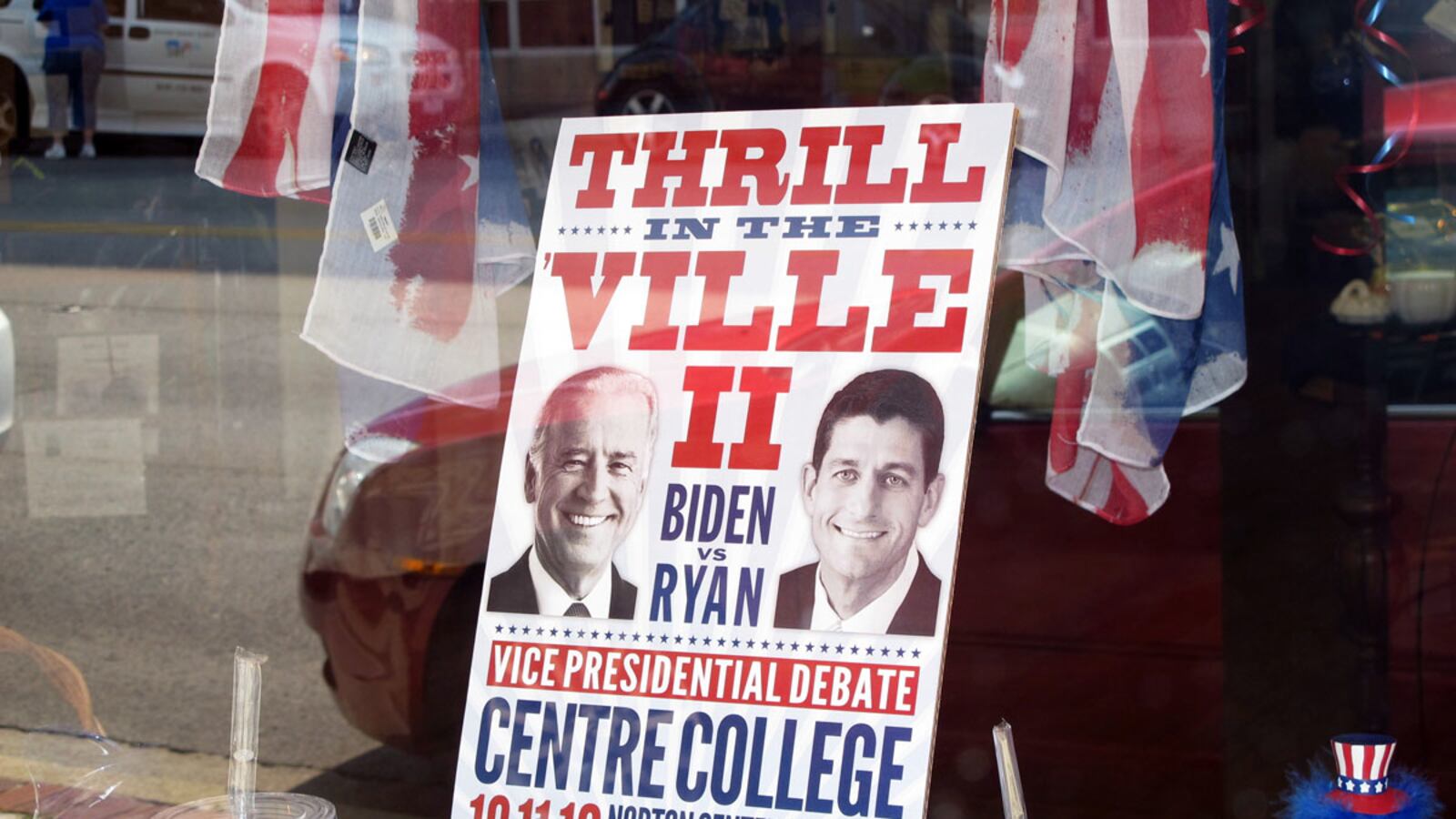

Centre College in Danville, Ky., the site of this year’s vice presidential debate, spent about $3.3 million. It was also Centre’s second time hosting a debate.

“When you accept the offer to become a debate site, what comes with it is a whole host of things to provide,” says Centre’s president, John Roush. “We had about 600 people in the audience. There’s a huge laundry list of things you have to provide to the media, the commission, and to the Secret Service.”

Others schools that have hosted include Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, Belmont University in Nashville, and the University of Mississippi; only occasionally does a more famous school such as UCLA provide the venue. The largest school picked this year was the University of Denver, which hosted the first presidential debate.

Despite the onerous requirements and restrictions, the host schools are drawn by a priceless level of free advertising.

Most of the applicants, says McCurry, a former White House press secretary, are not “large, well-known universities like Stanford, Harvard, Princeton, and the University of California. For smaller schools that would like to be better known and have a great story to tell, this is a good platform to tell it,” he says.

Rabinowitz says Hofstra noticed a definite increase in public interest after hosting its first debate in 2008. He says the school’s name was listed as the 12th Google search term on the night of the debate, and that the number of Hofstra applicants rose 20 percent.

“I think building a national brand is not a one-shot deal. Getting it twice persuaded people that it wasn’t a fluke that we got it once. They don’t come back twice to a place unless they love it,” Rabinowitz says. “We really do believe that it’s part of our mission here too. You can’t make your students vote or get interested [in politics], but you can sure inspire them.”

Centre College also noticed an immediate 10 percent increase in applications and a surge in alumni donations. This year U.S. News & World Report listed the school among the top 10 that receive the largest alumni support.

Both schools say they would do it again.

“There is absolutely no doubt that we will try in my mind,” says Rabinowitz. “It won’t be easy, that’s for sure. I don’t think three times in a row to win a presidential debate has ever been done before, but that’s part of the allure.”