The day after Jeffrey Epstein killed himself, a man wearing a red hoodie and L.A. Dodgers cap emerged from the dead sex offender’s Manhattan mansion. His hat and shades obscured his face as he hauled a hefty blue gift bag out of the massive townhouse, where Epstein abused scores of underage girls for years.

A photographer captured the scene that day in August 2019, and the pictures were published by the Daily Mail, which identified the mystery man as Epstein’s longtime accountant and a co-executor of his $634 million estate: 47-year-old Richard Kahn. The bag he was carrying, a source with close ties to Kahn said, contained Epstein’s funeral clothes.

Little is known about Kahn outside his work for Epstein. Or about his co-executor, 55-year-old Darren Indyke, who served as Epstein’s personal attorney for more than two decades and was apparently so close to Epstein that the money manager paid for fertility treatments for Indyke and his wife. Neither man has a public social media account, and both shun press interviews.

But both could soon be questioned as part of a lawsuit filed by Jane Doe, who alleges she was 14 when Epstein and his former girlfriend, British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell, began to groom and sexually abuse her in 1994. (Doe is suing Indyke and Kahn in their capacity as co-executors, and Maxwell individually.)

Maxwell, who is in a federal prison in Brooklyn awaiting trial for her alleged role in Epstein’s teen sex ring, could also sit for a deposition in Doe’s lawsuit.

Ghislaine Maxwell

Rob Kim/GettyLast week, Doe’s attorney wrote the federal judge overseeing the case and indicated Indyke would be deposed “in both his personal capacity and as a co-executor of the Epstein Estate,” and would “offer extremely relevant testimony” relating to her claims.

“Indeed, we have reason to believe he has firsthand knowledge of Jeffrey Epstein’s relationship with Plaintiff while she was a minor and even acted on Jeffrey Epstein’s behalf to communicate with Plaintiff on several occasions,” the lawyer Robert Glassman wrote to U.S. District Judge Debra Freeman, responding to the estate’s push to delay the under-oath grilling.

Doe also plans to depose Kahn. In an email thread attached to his letter, Glassman told the lawyer for Epstein’s estate, “With respect to Mr. Kahn testifying in his personal capacity, we would like to know to what extent he knew about Mr. Epstein and Ms. Maxwell’s criminal enterprise. We would like to know if Mr. Epstein had ever told him that he sexually abused and raped my client and other minor victims.”

“I trust you would agree that even if Mr. Kahn started working for Mr. Epstein after Mr. Epstein stopped abusing my client that doesn’t mean Mr. Kahn wouldn’t or doesn’t know anything about it. Right?” Glassman added.

The estate asked that the judge postpone Kahn’s and Indyke’s depositions, not only because they’ve yet to provide discovery materials requested by Doe, but also because Maxwell is requesting a stay in the case pending her criminal trial.

Last week, the judge put the depositions on hold until the court resolves Maxwell’s request and directed Doe’s legal team to find a new deposition date for Indyke in September should Maxwell’s motion be denied.

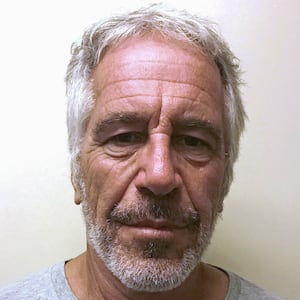

Jeffrey Epstein died by suicide after being charged with sex trafficking by federal prosecutors.

Shannon Stapleton/ReutersDoe isn’t the only survivor who tried to get sworn testimony from Indyke. Victims in other lawsuits, including a case brought by Annie Farmer, were scheduled to depose him, but their participation in a victims’ compensation fund put their cases on hold. (Applicants are not required to stay their litigation until they accept an offer from the fund.)

“One of the ironies is that as Epstein’s executor, by agreeing to set up this claims process, he may succeed in insulating himself from discovery,” one source familiar with the victims’ litigation told The Daily Beast. The source said Indyke “was plucked out of obscurity by Epstein” and described him as the “in-house counsel to Epstein’s enterprise.”

“He was involved in virtually all of the legal work Epstein had,” the source added. “He’s probably the person with the most knowledge about Epstein’s money, business relationships, assets, and legal affairs.”

“He’s a mystery in part because he’s been with Epstein so long," the source said. “He’s been Epstein’s confidant and aide for decades. If he had a life outside of Epstein, it was a very private life.”

Indyke and his criminal defense lawyer Marc Agnifilo, hired amid the government’s ongoing probe of Epstein and his companies, did not return messages left by The Daily Beast. His relatives also declined to comment.

The father of two worked as Epstein’s personal attorney since the 1990s, serving as an officer for the financier’s charities, handling feuds with unpaid contractors, and representing the businesses of women in Epstein’s circle. In 2012, he signed corporation paperwork for the design business of Sarah Kellen, an alleged co-conspirator of Epstein whom Palm Beach cops were ready to charge in their 2006 probe. (Kellen was a named accomplice in Epstein’s 2008 plea deal, which shielded her from prosecution.)

As The Daily Beast has previously revealed, Indyke also represented the women’s empowerment business of Lana Pozhidaeva, a Russian model in Epstein’s orbit. In 2018, Indyke filed trademark paperwork and registered the website for Pozhidaeva’s business, WE Talks. Records show that weeks after Epstein’s suicide, Pozhidaeva swapped Indyke for another lawyer.

Lana Pozhidaeva

Cindy Ord/GettyIndyke’s name is also on corporation filings for the anonymous company that owned Maxwell’s East 65th Street townhouse. In 2000, Epstein’s friend Lynn Forester sold the residence to the LLC for $4.95 million, according to reports.

He served as a trustee of Maxwell’s Max Foundation from 2001 to 2010, until he was replaced by Dana Burns, a woman pictured in society photos with Epstein and who also worked for Maxwell’s ocean nonprofit, The TerraMar Project.

Meanwhile, Indyke was listed as secretary of The Wexner Foundation—a nonprofit founded by Epstein’s only known clients, ex-Victoria's Secret mogul Leslie Wexner and his wife Abigail—in SEC filings from 1998 to 2001. The nonprofit’s tax forms also listed Indyke as secretary through 2006. Two years later, Abigail Wexner gave Indyke power of attorney over her condominium at 15 Central Park West, property records show.

Friends from high school and throughout Indyke’s life were surprised to see his name connected to Epstein in the press after the hedge-funder died.

Indyke grew up in a middle-class family in Glen Cove, a small city on the north shore of Long Island. Childhood pals told The Daily Beast he was a sweet, normal guy who was actively involved with theater from a young age through high school.

In his 1982 senior yearbook, Indyke wrote that in 20 years, he would be “‘performing’ [his] first case for the Supreme Court quoting Al Pacino,” Yahoo Finance reported.

He graduated from Colgate University in 1986 and Cornell Law School five years later. One former friend who grew up on his block said, “Even when he was in high school, he knew he was going to law school.”

“He was driven. Everything he did was towards becoming an attorney. It was something his parents wanted,” the friend added. When the acquaintance got in trouble for selling ice cream at Jones Beach in the early 1980s, he panicked and told an officer his name was something like “Darrel Endike” and gave an address that was slightly off.

Somehow, the pal told The Daily Beast, officials discovered the correct spelling and address for Indyke and appeared at his doorstep over the illegal vending. “His father, Bernie, was furious,” the friend said, adding that “he marched over to my house and confronted my father. I got into all kinds of trouble. The point was: that [Indyke] needed an unblemished record because he wanted to go to law school, and something like this could have hurt him in some way, his chances of going to a top law school.”

“I think I apologized to him [Indyke] for sure,” the friend said. “But it was really his father who was most upset.”

After law school, Indyke did a four-year stint with Gold & Wachtel, a now-defunct boutique law firm, and represented several clients in copyright lawsuits.

Gold & Wachtel represented Epstein at least as far back as 1988. Firm principal William Wachtel declined to discuss that but said he hired Indyke as a favor to the younger man’s father, Bernard Indyke, whom he described as a mailroom employee at a financial company that had retained Gold & Wachtel.

Court records indicate Indyke’s father was in fact a manager and member of the board at Jackie Fine Arts, a Gold & Wachtel client that sold low-value art reproduction rights to the rich at high prices as a calculated tax dodge. Efforts to reach the founder of the company, Herman Finesod—once hailed as the King of Tax Shelters—were unsuccessful.

“You find someone successful and hitch your wagon to them,” a childhood friend of Indyke’s, who last saw him when they were in their twenties, told The Daily Beast. “People fall into these situations and they can’t extricate themselves… That’s the benefit of the doubt I would give him.”

Indyke perhaps felt indebted to Epstein for his largesse.

As Indyke wrote in a glowing biography of his boss—prepared for Florida prosecutors—Epstein paid for “prohibitively expensive in-vitro fertilization cycles,” for him and his wife.

“Shortly after I began working for Jeffrey, I experienced a personal and unexpected tragedy. After five years of marriage, my wife and I learned that I was infertile and we could not have children in the traditional manner,” Indyke wrote in the bio, first reported by The Palm Beach Post.

“I meekly approached Jeffrey and asked him if it would be possible to drop my wife and me from the company’s medical policy in exchange for a different one or cash payment,” Indyke continued. “Puzzled by my request, Jeffrey naturally asked why. When I told him, he was visibly affected and without even a moment’s consideration, he told me to go for treatment and send him the bills. Having been with Jeffrey only a few months, I was astounded by his generosity and hurried to my desk to call my wife to share the amazing news.”

Indyke claimed Epstein paid for five cycles of in-vitro, and that Maxwell even offered to look into adoption for his family.

“At the unsuccessful completion of our fourth cycle and a failed adoption attempt, my wife and I were at the end of our rope and did not want to continue,” Indyke declared. “Without Jeffrey’s support and stubborn daily encouragement we would not have. He even recruited his then girlfriend, Ghislaine Maxwell, to meet with us to offer assistance with local adoption and overseas adoption procedures and to encourage us to try again.”

“Thankfully, after our fifth cycle, my wife and I were blessed with twin daughters. Although Jeffrey was adamant that we owed him nothing, Jeffrey honored us by agreeing to be the godfather of our children.”

In the past decade, Indyke and his wife have owned two different properties in Boca Raton, Florida—one of which they still own, having acquired it for $3.1 million without a mortgage in 2015. Another, bought in 2014 and sold four years after, sat in the exclusive enclave of Boca Grove Plantation; it required the pair to shell out at least $70,000 beyond the $460,000 purchase price for a “social equity membership in the Boca Grove Golf & Tennis Club.”

All the while, they maintained a residence in Livingston, New Jersey, which they purchased through an LLC for $1.75 million in 2003.

In his recent book, Relentless Pursuit, longtime victims’ lawyer Brad Edwards described Indyke as Epstein’s “fixer” who “had attended important hearings as well as my depositions of Epstein over the years.” When Edwards sat for a 2017 deposition in his years-long court battle with Epstein, Indyke was there to take notes. “Darren Indyke, who was a staple at every Epstein event, was situated in his normal spot at the far end of the table in order to monitor and report back to Epstein everything that happened,” Edwards wrote.

“He wasn’t a litigator, more like a fixer,” Edwards noted at another point. “Indyke had one client: Jeffrey Epstein.”

Lawyer Brad Edwards

Johannes Eisele/GettyEdwards represents a client referred to as Katlyn Doe, who alleges in a lawsuit that Epstein forced her to marry one of his non-citizen female recruiters—nuptials arranged, she says, through Epstein’s “long-time New York attorney.”

“The ceremony included not only signing the necessary legal paperwork prepared by [the attorney] but also posing for photographs to give the appearance that the marriage was legitimate,” the complaint states. Whether Indyke was this attorney hasn’t been publicly confirmed. Edwards could not be reached for comment.

Kahn is a lesser-known figure in Epstein’s world, and his name is hardly mentioned in litigation related to the sex-offender’s victims.

There were no public images of the accountant until the Daily Mail’s photos of him transporting the gift bag in August 2019, along with snapshots of him leaving Epstein’s home in February 2019 following a two-hour visit.

Days after the Mail published the images, an attorney for one victim wrote to Kahn’s lawyers, demanding materials be preserved.

“Is it true that Mr. Kahn entered Mr. Epstein’s townhouse and removed documents?” the lawyer wrote, before requesting “a list of documents and/or materials Mr. Kahn removed from Mr. Epstein's townhouse that day and on any other occasion after Mr. Epstein's death.”

Counsel for the Epstein estate dismissed the Mail report and told the victim’s team via email: “Our clients take their preservation obligations seriously.”

A person with knowledge told The Daily Beast that the bag contained funeral attire and that Kahn “was doing his obligation as an executor which is to attend to the burial details.”

The source said Kahn “has never socialized with Epstein” and wasn’t aware of Epstein’s alleged abuse. Kahn first met Epstein when he began working for him in 2005, out of a Madison Avenue office he shared with Indyke. (An accountant named Bella Klein, and Epstein’s personal assistant and alleged co-conspirator Lesley Groff, also routinely worked in the New York office.)

“Richard worked out of the office,” the source added. “Did Epstein appear at those offices? Yes. Did Richard see any of the activities that were the focus of press attention? No.”

Kahn’s name appears throughout records for Epstein’s nonprofits and corporations and was mentioned in the 2010 deposition of Epstein’s Palm Beach house manager, Janusz Banasiak, who described him as a senior accountant.

“Would you say that Mr. Kahn is a key employee, like a right-hand man of Mr. Epstein?” one victim’s lawyer asked. Banasiak replied in the affirmative.

Kahn is listed as treasurer of Epstein’s Financial Strategy Group Ltd. (FSG), which filed an application in 2013 to become an international banking entity based in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Indyke was secretary and Epstein president, records show.

FSG, which changed its name to Southern Country International, was approved in 2014 to run a bank specializing only in offshore clients. In 2018, Erika Kellerhals, Epstein’s tax lawyer based in St. Thomas, told territory officials the bank’s operations hadn’t yet begun. According to The New York Times, whether the bank actively pursued customers is unclear. But months after Epstein died, the estate transferred more than $12 million to Southern Country's coffers. The bank’s year-end value was $499,759 two weeks after the transfer, the Times reported, and what happened to the money isn’t clear.

According to FSG’s articles of incorporation, Kahn became a certified public accountant in 1995. He graduated from Syracuse University in 1994 and got a masters in taxation from Pace University in 1999.

Kahn and his wife, Lisa, purchased a $2.8 million co-op apartment on the Upper East Side in 2008, property records show, and they took out a mortgage on that residence in 2016. The couple also owns a six-bedroom Hamptons manse purchased for $1.5 million in 2015.

Kahn, who declined to comment for this article, has been an executive with Epstein’s shadowy nonprofits since at least 2007.

That year, Kahn replaced Maxwell as treasurer of the C.O.U.Q. Foundation and held the role until the charity dissolved five years later.

C.O.U.Q. contributed $46 million in stock and other assets to Wexner’s YLK Charitable Fund in 2008, just before Epstein started his Palm Beach jail sentence. According to one CNBC report, Epstein’s nonprofit gave $14 million to YLK in 2007.

Before C.O.U.Q. shut down in November 2012, Epstein created another murky entity called Gratitude America Ltd.

The charity’s tax filings didn’t show revenues until 2015, when Kahn replaced Epstein as president of the group and investor Leon Black donated $10 million through an anonymous LLC. The attorney general of the U.S. Virgin Islands recently issued civil subpoenas to Black over his relationship with Epstein.

Deutsche Bank AG, where Gratitude America had an account, is also under fire over its relationship with Epstein. In July, the bank was fined $150 million for failing to detect millions in suspicious transactions, including payments to Epstein’s alleged co-conspirators and more than $800,000 in withdrawals made by Epstein’s personal attorney.

Similar to Indyke, Kahn made political donations to the same candidates Epstein backed throughout the years.

In 2007, Kahn and his wife each made $2,300 donations to the presidential campaign of former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, a friend of Epstein. Indyke and his wife, Michelle Saipher, also donated $2,300 apiece to Richardson that year. (One of Epstein’s victims, Virginia Giuffre, claims Maxwell directed her to have sex with Richardson. He has denied involvement with Epstein’s trafficking scheme.)

Kahn donated a total of $5,400 to the campaign of Congresswoman Stacey Plaskett of the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2016, and $2,700 in 2018. He shelled out $2,600 to Plaskett in 2014 (as did fellow Epstein accountant, Bella Klein). After Epstein’s July 2019 arrest, Plaskett said she’d return Epstein’s money, though it’s unknown whether she planned to return the funds of his associates.

In the itemized receipts for the 2016 and 2018 donations, Kahn’s occupation is listed as “attorney.” He’s never been registered, however, as a lawyer in New York state.