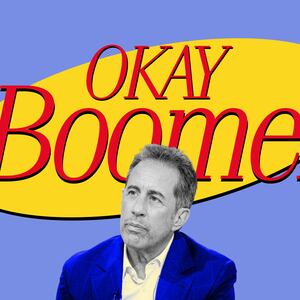

One would be forgiven for wondering what world Jerry Seinfeld is living in where the “extreme left,” as he claimed in a recent interview with The New Yorker, has purged American television of good comedy. For all the left’s mighty powers, it couldn’t quite manage to halt production of biting network comedies like Abbott Elementary, Superstore, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, or The Good Place. Nor did it manage to stave off dark, even transgressive cable fare like It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, The Righteous Gemstones, Atlanta, or PEN15.

The Democratic Socialists of America certainly didn’t stop Seinfeld’s erstwhile collaborators, Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Larry David, from making Veep and Curb Your Enthusiasm, respectively, the latter of which just ended a critically acclaimed final season.

And as Seinfeld himself acknowledged, the left’s path of destruction has yet to temper the spread of deliberately offensive stand-up comedy, a field that includes many proud right-wingers who consider it their business to make comedy racist, sexist, and transphobic again. So what, exactly, is the creator and star of one of the greatest sitcoms of all time complaining about?

Perhaps his problem is less with the left’s influence on television than with the left, period. Seinfeld, whose net worth recently passed $1 billion, has long fashioned himself an apolitical comedian, but of course he’s far from an apolitical figure. A longtime donor to Democratic candidates and causes, he has also long been a full-throated supporter of the far-right State of Israel—not so much in the abstract sense of celebrities who wax poetically about Israel’s “right to exist” than in the concrete, enthusiastic sense of a man who once took his family to an IDF “fantasy camp” in the West Bank. There he participated in “shooting training with displays of combat,” according to the camp, and posed joyfully with the same soldiers enforcing the illegal occupation that, in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, has now seen the slaughter of tens of thousands of Palestinian men, women, and children.

It seems only natural that as public opinion turns against Israel—catching up with a left that has spent decades working to dismantle the apartheid state—so too should it sour on Seinfeld, who has remained a steadfast Zionist over these past six months. In late December, by which point the death toll in Gaza had passed 20,000, he met with hostages’ families in Tel Aviv. Last month, his wife Jessica contributed at least $5,000 to a pro-Israel counterprotest at UCLA. (She later claimed that these funds went towards a “peaceful” demonstration, not the violent mob that attacked a pro-Palestinian encampment.) And this past Sunday, as dozens of students walked out of his commencement address at Duke, he offered some advice to a supposedly over-sensitive generation: “It is worth the sacrifice of occasional discomfort,” he reportedly said, “to have some laughs.”

It’s an interesting message to send to a graduating class that in recent months has been exposed to suspension, expulsion, doxxing, misrepresentation and ridicule across mainstream media, arrest, and police brutality—and he’s an interesting man to say it.

What exactly does Seinfeld know about discomfort? His creative output since ending his eponymous sitcom 26 years ago this week has consisted chiefly of the animated Bee Movie; a television series in which he drives luxury automobiles with his friends; a short-lived reality show called The Marriage Ref; various sitcom appearances as himself; a Netflix special in which he complained about texting; and his widely panned directorial debut Unfrosted, the product of an obsession with Pop-Tarts that dates back to the early Obama era.

What’s so perplexing about Seinfeld’s advocacy for difficult comedy is that his own comedy has never been particularly difficult. He spent the 1990s making a broad, brilliant sitcom about terrible people that cemented his legacy as one of the great observers of modern life, its absurdities and trivialities. From there he went on to watch his bank account grow, occasionally taking a break to grace his fans with some project or another that technically qualified as funny. Which is his right: The wealthy owe us nothing but their taxes, and artists have no obligation to make interesting work. Still, it may concern comedy’s elder statesman—or at least those who hope to follow in his footsteps—that the world seems to be catching on to the fact that he has less to say than his eponymous show about nothing.

On the other hand, anyone who’s paid attention to the comedy world over the last 10 years will likely scoff at the idea that Seinfeld’s chronic complaints about political correctness, support for a state on trial for genocide, and embarrassing post-Seinfeld career might have any lasting effect on his legacy. As the comedian Matt Rife aptly observed last week, in a set that reportedly included transphobic jokes, cancel culture is not real: Comedians, especially very famous comedians, can do pretty much anything and come away with their reputations intact.

Louis C.K. has released four specials since confessing to sexual misconduct in 2017, one of which won a Grammy Award. Jeff Ross, accused of grooming a teenage girl in a virtually forgotten 2020 New York magazine exposé, just featured prominently in Netflix’s Roast of Tom Brady. Shane Gillis, a Trump fan with a prolific history of unequivocally bigoted remarks (who has repeatedly promoted Holocaust deniers on his podcast), is one of the most beloved comedians of our day with a new sitcom, Tires, premiering on Netflix next week. Tony Hinchcliffe, who called his opener a racial slur for Chinese people in 2021, appeared on the cover of Variety last month.

Seinfeld himself had a relationship with a 17-year-old girl when he was a 38-year-old TV star. If that didn’t affect his legacy, why would anything else?

It may be that a comedian’s greatest support system is their own peers, who operate powerful levers in the machine of public opinion. Consider that in the wake of Louis C.K.’s brief downfall, an army of his fellow comics defended him, cheered his return to the club scene in 2018, hosted him on their podcasts, and opened for him on his comeback tours. So too did they circle the wagons around Gillis, who received considerable post-scandal support from podcasters like Joe Rogan and Theo Von (and, indeed, from Louis C.K., who appeared on multiple episodes of Gillis’ podcast and hired him as an opener).

Ross floated through his controversy largely thanks to a Los Angeles comedy scene unbothered by inappropriate sexual relationships—perhaps because it was built on them—and less than a year later he was sharing a stage with Dave Chappelle. Do you remember the 2021 child sex abuse lawsuit against Saturday Night Live cast member Horatio Sanz that implicated Lorne Michaels, Jimmy Fallon, Tracy Morgan, Tina Fey, and Seth Meyers? That’s OK, neither does anyone else.

Comedians protect comedians. The industry operates as a social club with a code of silence so strong you’d think it must be a police force. Consider Chappelle—almost a decade into his anti-trans activist era, his diatribes have yet to dent his standing with even progressive comics like Jon Stewart, Patton Oswalt, and John Mulaney.

In Esquire last month, comedian Jerrod Carmichael revealed that Chappelle sought a public apology for comments Carmichael made in a 2022 GQ interview, in which he argued that the elder comic’s transphobia was tarnishing his legacy. Just two weeks after Esquire published the interview, Carmichael gave that apology: “Dave Chappelle is an artist—he’s one of the few artists that we have—and I care deeply about the work that he makes,” he said on The Breakfast Club (a show co-hosted by Charlamagne Tha God, whose accidental confessions to multiple acts of sexual assault did not deter Comedy Central from giving him a late-night series in 2021). “And I’ll tell you, honestly, from now on, any thoughts I have for Dave will be directed in a phone call to Dave. I’ll never do it again. I do apologize for that.”

Whether you’re an open mic comic, a podcaster, a headliner, or a TV star, comedy is essentially a business of favors: You put me on your show, I’ll put you on my show.

Amy Schumer starred in Unfrosted after hiring Seinfeld’s daughter Sascha to write on the latest season of Inside Amy Schumer and then her Hulu series Life & Beth. Perhaps more pertinently, comedy is an industry where everyone you meet may someday be able to give you the gig that changes your life. As the comedy historian Kliph Nesteroff speculated last year, this may be why we rarely see comedians speak ill of Chappelle or Joe Rogan—both figures ripe for critique who also have immense power to boost careers.

This has the natural effect of depressing speech on both sides of the coin. You’re not going to tear into someone like that before they give you the boost, and you’re certainly not going to tear into them after.

So long as Seinfeld maintains the respect of his peers, in other words, his legacy is unlikely to suffer from any political statements he makes or actions he takes. And if his recent appearance on John Mulaney’s Everybody’s in LA is any indication, he’s unlikely to lose the respect of his industry anytime soon.

This is what makes it so gratifying to see a handful of college graduates walk out on him, treating him with a level of contempt that nobody in his own industry of professional contempt artists has ever had the courage to muster. Like a solar eclipse or the northern lights, it’s a marvel we’re unlikely to witness again soon. Enjoy it while you can.