It turns out Mark Meadows may have good reason to not want to turn over all of the communications on two personal phones and two Gmail accounts.

After the Jan. 6 Committee disclosed just a few choice text messages between Meadows and Fox News hosts, an anonymous lawmaker, and Donald Trump Jr. about the insurrection, the battle for all of Meadows’ communications has taken on new meaning.

And Meadows’ assertions of executive privilege are undermined by a law he should know well.

Former President Trump’s chief of staff is refusing to turn over some personal emails, text messages, and encrypted chats by claiming that his old boss still retains some executive privilege over them.

But if that’s the case, the Jan. 6 Committee is now arguing, then Meadows should have turned those communications over to the National Archives on his way out the White House door.

“It appears that Mr. Meadows may not have complied with legal requirements to retain or archive documents under the Presidential Records Act,” reads a committee report released Sunday night. The report noted a growing concern that “materials may now be lost to the historical record.”

What little we know of those private communications is plenty damning enough. On Monday night, as the committee voted to hold Meadows in criminal contempt, Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) read aloud text messages to Meadows from Fox News hosts Laura Ingraham, Brian Kilmeade, Sean Hannity, and even Trump’s own son Don Jr., in which they all begged to have the president intervene. He did not.

Congressional investigators are particularly interested in how Meadows used his personal devices and accounts to coordinate several challenges to the 2020 election results—and the disastrous aftermath of the failed coup. Trump’s right-hand man in the White House played a pivotal role, most prominently in organizing the infamous Jan. 2 phone call during which Trump tried to pressure Georgia’s top elections official to “find 11,780 votes” and erase Joe Biden’s victory.

“Mark Meadows' texts and emails reveal deep involvement in setting the stage for the January 6 attack,” Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) tweeted Monday afternoon.

“Had Mr. Meadows been deposed under oath, the committee would have asked him about his handling official government records, a topic that is not subject to any conceivable legal privilege,” Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-FL) said during the contempt vote meeting Monday evening.

Meadows did not respond to a request for comment. In a Fox News interview Monday night, however, he defended his recalcitrant approach by claiming that Trump’s executive privilege claims are “not mine to waive.”

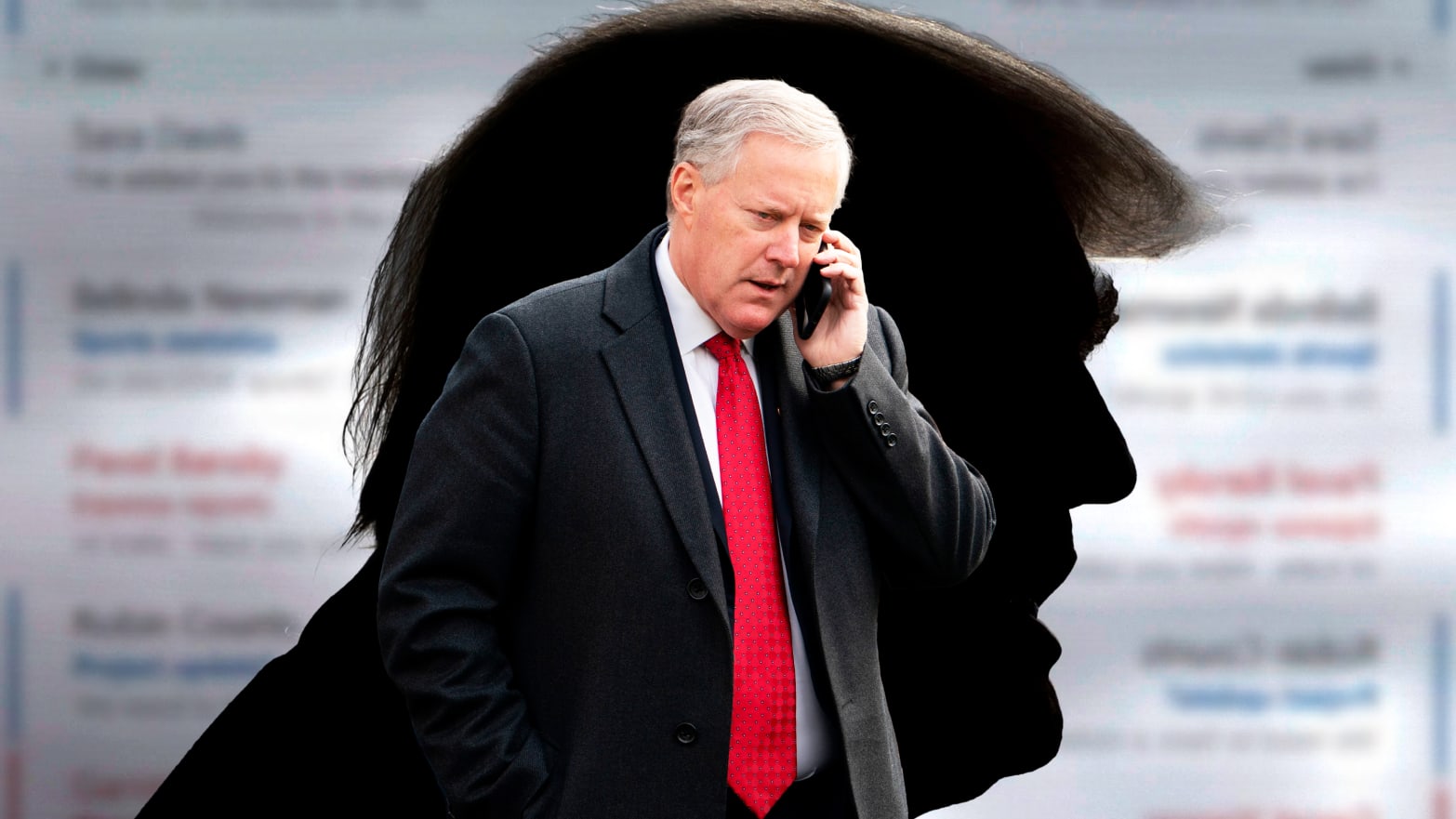

Former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows greets supporters before President Donald Trump speaks during a rally on Oct. 31, 2020.

Mark Makela/Getty

The use of a personal cellphone and two Gmail accounts means that Meadows, who may soon be held in contempt of Congress and face criminal charges, could also be fighting off accusations that he violated federal records laws.

Committee members want to ask Meadows about his texts with an organizer of the pro-Trump rally at the Ellipse, a park just south of the White House that served as a staging area before the violent assault on the U.S. Capitol building on Jan. 6.

Documents released by the special commission allege that Meadows discussed speakers and the locations of certain individuals. Members also want to question Meadows about text messages he sent to others on the line during the damning Trump Georgia phone call, as well as messages he sent members of Congress “regarding strategy for dealing with criticism of the call,” according to the committee.

Among the communications also drawing their scrutiny: his chats about Trump’s potential 2024 run and his conversations he had about a potential job at a news network.

Meadows has already turned over nearly 9,000 pages of documents requested by the committee. But the committee is still coming after him, because of his reluctance to turn over some evidence about inner workings at the Trump White House—and his refusal to sit down for sworn testimony behind closed doors.

And if what Meadows has already turned over to investigators is any indication, the former Trump chief of staff used his personal phone for quite a bit of government work.

“Mr. Meadows’ production of documents shows that he used the Gmail accounts and his personal cellular phone for official business related to his service as White House chief of staff,” reads the latest committee report. “Given that fact, we would ask Mr. Meadows about his efforts to preserve those documents and provide them to the National Archives.”

There’s a bit of irony here. Meadows made it to the White House after years of being one of Trump’s most loyal allies in Congress, where he previously served as the chairman of the House Freedom Caucus and one particular subcommittee: Oversight and Government Reform’s panel on government operations.

That subcommittee actually oversees the management of federal records, which means Meadows is well-versed in the rules regarding government communications.

In fact, Meadows used his subcommittee to look into the IT specialist who worked on Hillary Clinton’s private email server, which fueled a seemingly endless debate about the improper use of personal devices.

Meadows, who was highly critical of Clinton’s private email server for years, later defended Trump administration officials who used private devices for official business, with one important caveat: that they turn over the device.

That was the case with former Trump diplomats Kurt Volker and Gordon Sondland, who were wrapped up in the first Trump impeachment case over Trump’s phone call to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. And Meadows has previously addressed charges of hypocrisy, claiming that the difference was that Clinton was dealing with classified materials.

But Meadows seems to want carte blanche to personally determine what’s private and public, while simultaneously arguing that the information he claims is shielded by executive privilege is also shielded from being turned over to the National Archives.

That argument may prove to be a tenuous one.

Meadows appears to have also used two cellphones with North Carolina area codes, according to the Jan. 6 Committee. At least one of them—a phone line belonging to “Meadows for Congress”—was the target of a committee subpoena that was sent in November. Investigators want to see that phone’s metadata and subscriber information, along with a log of calls, text messages, voicemails and other connections during his last four months in the White House.

His political group stopped paying for its Verizon account in November 2020, just as Meadows began helping Trump with his despotic attempt to stay in power. This raises the question of whether Meadows was using a personal phone for White House business—while it was possibly being paid for by donor funds from his congressional campaign.

Meadows, who was targeted last fall in a complaint to the Justice Department for allegedly tapping tens of thousands of dollars in campaign funds for personal use, charged monthly phone bills to his campaign. The practice is common among elected officials who keep a separate cell specifically for campaign activity, such as fundraising, travel, and contacts with a tight political circle.

Although Meadows converted the campaign to a leadership political action committee in July, shortly after leaving Congress for the White House gig, federal filings appear to show that he continued using it for personal expenses, including those cellphone payments.

Federal election laws restrict how officials are allowed to use phones underwritten by donor cash. But the late-November cutoff suggests a meaningful change in status at a significant point in time—just as Trump was ramping up the post-election chicanery. While the House select committee’s subpoena reaches back before the election, the most significant discussions and text messages would have fallen well after the reported payments ceased.

It’s unclear whether Meadows stopped using his official line, and, if he did, when and why.

Don W. Wilson, who served as the nation’s archivist from 1987 until 1993, told The Daily Beast that there’s little wiggle room here.

“If it’s official business, then it’s a record. And by the nature of his role and his office, there’s not much unofficial,” he said. “He shouldn’t have been using his personal cellphone… and if he was, there should have been some sort of transfer to the National Archives.”

The federal government’s gargantuan library has found itself at the center of a fight between the bipartisan Jan. 6 Committee and Trump, who claims that vast troves of his presidential records should be kept secret, somewhat bafflingly, for the sake of the Republic. His legal challenge has already lost twice—once in district court and again on appeal—but until the case is officially resolved, the National Archives isn’t turning over evidence to investigators.

Wilson, who has been watching this unfold from his home in South Carolina, hopes the presidential records will be turned over.

“Theres’ a real need for someone, and it’s probably Congress, to get to the truth,” he said. “And the only way they can get to that is through the records and witnesses. But a lot of it is going to have to come through the texts.”

Meadows is being especially guarded about his personal cellphone’s text messages, and that issue appears to be what derailed negotiations between him and the Jan. 6 Committee. While Meadows was quietly fighting off a subpoena to testify, he was turning over records. That is, until he discovered that the committee sent Verizon a subpoena for his old phone’s records. When investigators crossed that line, Meadows cried foul and sued the committee.

Wilson said Trump’s insistence to keep call logs secret—and Meadows’ reluctance to turn over text messages—foreshadows just how damning they may be.

“What were the texts? What were the phone calls? If they can’t even get the logs for the official phone calls, that’s pretty revealing,” he said. “It’s going to come out eventually. But what it’s doing to the country right now is a travesty.”