2025 wasn’t a particularly great year to be gay in America—rising hate crimes, hate speech and culture wars collided with a record amount of anti-LGBTQ legislation.

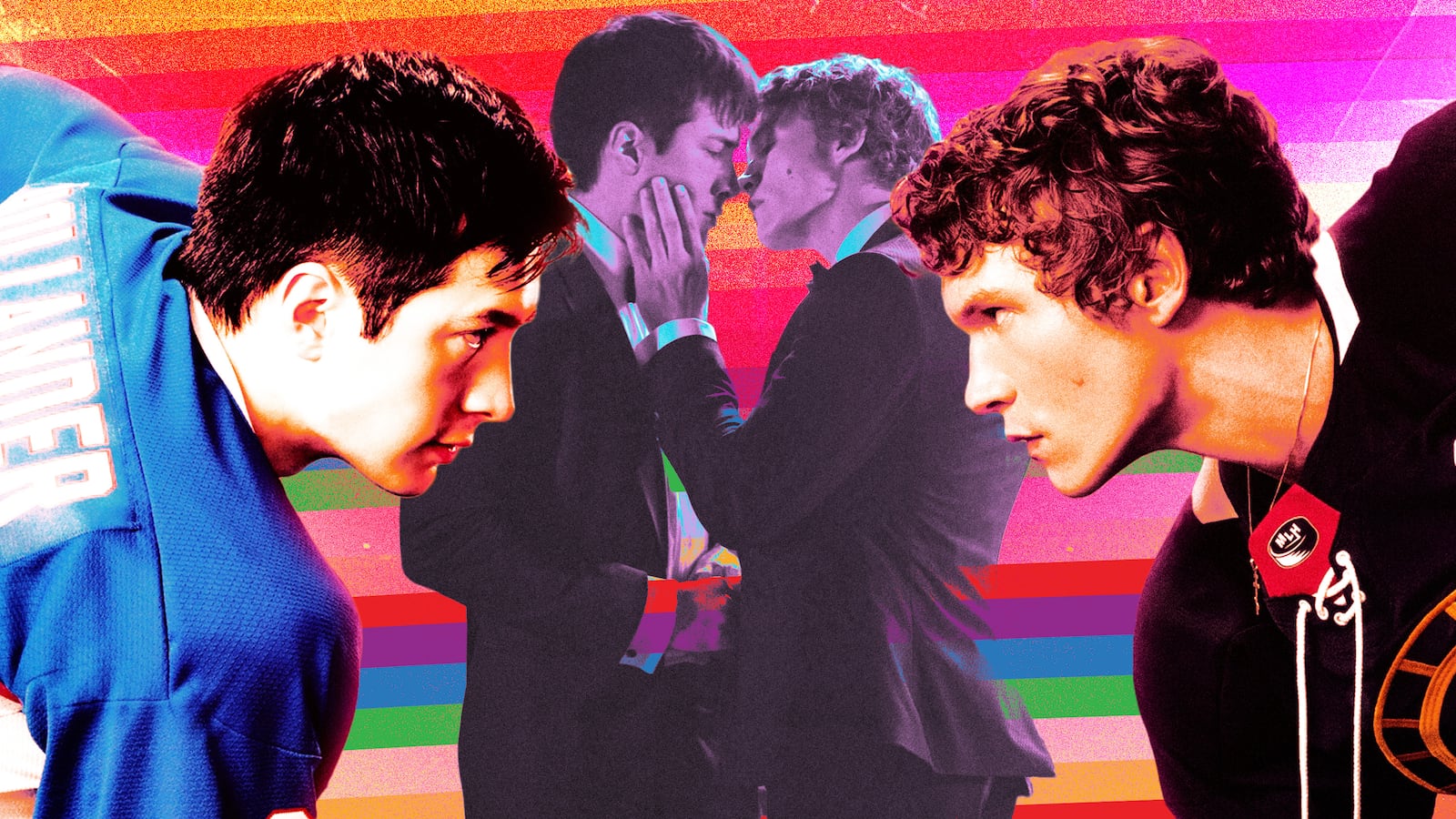

And yet, it was also the year of “gay hockey smut.” Heated Rivalry, a Canadian production that exploded after its pickup by HBO Max, dominated the year-end zeitgeist, extending its cultural chokehold—consensual and tender, thanks very much—into 2026. Between fan edits, social media fawning (and backlash to the fawning), think pieces and headlines, the very gay show is approaching the point where it almost feels monocultural.

I like Heated Rivalry well enough and think its unapologetic showcasing of gay sex is important. It’s a fantasy in the truest sense of the word—glamorous and masculine jobs, wealth, and centered on a mess of men with gravity-defying derrieres having expertly lit sex with zero hiccups—which isn’t a critique of the show, mind you. But I was initially surprised it became as big of a deal as it did, especially since there were other gay-centered shows in the recent past—Boots, Fellow Travelers—I found more compelling and, frankly, hotter.

Perhaps that’s why Heated Rivalry’s mass appeal has transcended gay viewership: Boots and Fellow Travelers were both explicitly political shows that dealt with how gay men’s lives in America are policed, forcing the audience to do some self-interrogation. (It’s worth noting that despite critical acclaim and strong viewership numbers, Boots was canceled by Netflix days after a spokesperson for Pete Hegseth called it “woke garbage”). While Heated Rivalry certainly has the spectre of discrimination hanging over it—its primary leads are two men (one of them, Russian) who feel they can’t be out in their professional-public lives—for all intents and purposes, it’s an apolitical fantasy, without the messy realities of rights, safety, or healthcare that impact being gay in America today. It’s the scintillating escapism many of us need.

Heated Rivalry offers audiences a world in which gay longing, love, and just-short-of-pornographic gay sex can exist without the politics that inherently govern all three. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that its highly rated finale takes place tucked away in a rural retreat where the two stars need only worry about one another.)

And to be clear, Heated Rivalry is romantic fiction. Book author Rachel Reid and showrunner Jacob Tierney accomplished exactly what the genre requires. But while fiction can get away with erasing the legislature and culture wars, insisting gay life isn’t political in real life blurs the lines between fantasy and farce.

Take a December Wired interview with George Arison, the CEO of Grindr (the pre-eminent gay networking app). “Grindr is not in the business of politics at all,” Arison said, attempting to position the app not just as somewhere men who are attracted to men go to hook up, but as the “everything app for the gay guy.”

What makes Arison’s claim here especially insulting is that it comes from someone who’s uniquely positioned to understand just how much politics affects LGBTQ life—he’s the CEO of a gay networking app, married to a doctor who used to work for the World Health Organization. But Arison is also someone whose own alleged conservative politics and personal privilege place him squarely outside the experiences of most queer Grindr users. His insistence that Grindr can exist outside of politics reads as out of touch at best and deeply insidious at worst.

It’s also deeply misleading since Grindr’s been actively involved in the political arena. In 2024, it got into the lobbying game (with Politico reporting it’d be tackling issues like HIV prevention and surrogacy, which are routinely threatened by Republican-led legislation) and publicly backed legislation this past fall. The company’s Head of Government Affairs, meanwhile, formally served as chief of staff for Republican Senator Deb Fischer (who has a history of opposing LGBTQ rights),

“It’s socially irresponsible for a company that serves any marginalized community to believe that they can run their business without politics,” argued Dr. Kevin Nadal, a Distinguished Professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, who researches the effects of microaggressions on the LGBTQ population.

“The fact that Grindr runs ads to assist in HIV awareness and prevention is, in fact, a political move. The fact that they allow people to write their gender identities and pronouns is a political move,” Nadal told The Daily Beast. “The whole existence of a company that is based on behaviors that were once deemed illegal and immoral, ‘crimes against humanity’, is political.”

“I’d say Grindr is political and that you cannot in this day and age, run a business and claim it’s not,” added Dr. Michael Bronski, a professor of Media and Activism at Harvard and author of the book A Queer History of the United States. “But you can certainly deny that it’s political to your own advantage.”

This contradiction isn’t unique to Grindr. Across politics, media, and corporate culture, allyship has increasingly become aesthetic rather than material—expressed through public-facing language, branding, and cultural consumption, while political commitments quietly move in the opposite direction. Consider how Disney initially treated Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill as something to remain neutral on, only reversing course after sustained internal and public backlash; or how NHL commissioner Gary Bettman—who’s been criticized for anti-LBGTQ stances and participating in Trump’s sports council—just jumped on the Heated Rivalry bandwagon, praising it as “a lot of fun.”

In other words, an “apolitical” stance increasingly functions as a branding choice—a PR smokescreen—that often masks quiet alignment with power, but in reality, can’t hold up against the structural forces shaping and limiting LGBTQ life. Because make no mistake, plenty of today’s most powerful politicians have made it their business to ensure it’s hard for gay Americans to obtain that fabled “liberty and justice for all.”

The bulk of the world’s—not just America’s—LGBTQ population keep themselves in a “huge” global closet. Politics is a huge part of that, because confronting how it polices your life once out is scary. “I think it’s important to actually articulate, right? That people don’t come out not because they want to be private, but because they’re afraid of something,” Bronksi explained. While it might not be explicitly stated, politics influence the closeted status of the characters in Heated Rivalry. Politics influence why so many profiles on Grindr are blank or anonymous.

“Whether it’s how the government is defunding our healthcare or educational programs, or how our rights to marriage or adoption are being threatened, being gay and out in America is inherently political, whether people recognize it or not,” Nadal said. “To be out and gay in this current world is a political statement.”